By Mark J. Spalding, President

Groundhog Day All Over Again

This weekend, I heard that the Vaquita Porpoise is endangered, in crisis, and in desperate need of immediate protection. Unfortunately, that is the same statement that can be, and has been, made every single year since the mid-1980’s when I first began working in Baja California.

Yes, for nearly 30 years, we have known about the Vaquita’s status. We have known what the major threats to the Vaquita’s survival are. Even at the international agreement level, we have known what really needs to be done to prevent extinction.

For many years, the US Marine Mammal Commission has strongly considered the Vaquita as the next most likely marine mammal to go extinct, and dedicated time, energy and resources to advocating for its conservation and protection. A substantial voice at that commission was its head, Tim Ragen, who has since retired. In 2007, I was the facilitator for the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation’s North American Conservation Action Plan for the Vaquita, in which all three North American governments agreed to work to address the threats quickly. In 2009, we were a major supporter of a documentary film by Chris Johnson called the “Last Chance for the Desert Porpoise.” This film included the first-ever video photography of this elusive animal.

The slow-growing Vaquita was first discovered via bones and carcasses in the 1950s. Its external morphology was not described until the 1980s when Vaquita began to appear in the fishermen’s nets. The fishermen were after finfish, shrimp, and more recently, the endangered Totoaba. The Vaquita is not a big porpoise, usually well under 4 feet in length, and is native to the northern Gulf of California, its only habitat. The Totoaba fish is a marine fish, unique to the Gulf of California, whose bladders are sought after to meet the demand in the Asian market despite the illegality of the trade. This demand began after a very similar fish native to China became extinct due to overfishing.

The United States is the primary market for the northern Gulf of California shrimp fisheries. The shrimp, like the finfish and endangered Totoaba are caught with gillnets. Unfortunately, the Vaquita is one of the accidental victims, the “bycatch,” that is caught with the gear. The Vaquita tend to catch a pectoral fin and roll to get out—only to become more entangled. It is a small comfort to know that they appear to die quickly of shock rather than slow, painful asphyxiation.

The Vaquita does have a small designated refuge area in the upper gulf of the Sea of Cortez. Its habitat is slightly larger and its entire habitat, unfortunately, coincides with major shrimp, finfish and illegal Totoaba fisheries. And of course, neither shrimp nor Totoaba, nor the Vaquita can read a map or know where the threats lie. But people can and should.

On Friday, at our Sixth Annual Southern California Marine Mammal Workshop, there was a panel to discuss the current status of the Vaquita. The bottom line is tragic, and sad. And, the response of those involved remains upsetting and inadequate—and flies in the face of science, common sense, and true conservation principles.

In 1997, we were already extremely worried about the small size of the population of the Vaquita porpoise and its rate of decline. At that time there were an estimated 567 individuals. The time to save the Vaquita was then—establishing a full ban on gillnetting and promoting alternative livelihoods and strategies might have saved the Vaquita and stabilized the fishing communities. Sadly, there was no will among either the conservation community or the regulators to “just say no” and protect the porpoise’s habitat.

Barbara Taylor, Jay Harlow and other NOAA officials have worked hard to make the science related to our knowledge of the Vaquita robust and unassailable. They even convinced both governments to allow a NOAA research vessel to spend time in the upper Gulf, using big eye technology to photograph and do transect counts of the abundance of the animal (or lack thereof). Barbara Taylor was also invited and allowed to serve on a Mexican presidential commission regarding the recovery plan of that government for the Vaquita.

In June 2013, the Mexican government issued Regulatory Standard number 002 which ordered the elimination of drift gill nets from the fishery. This was to be done at approximately 1/3 per year over the space of three years. This has not been accomplished and is behind schedule. In addition, scientists had instead suggested a complete closure of all fishing in the habitat of the Vaquita as soon as possible.

Sadly, in both today’s US Marine Mammal Commission and among certain conservation leaders in Mexico, there is accelerated commitment to a strategy that might have worked 30 years ago but today is almost laughable in its inadequacy. Thousands of dollars and too many years have been devoted to the development of alternative gears to avoid disrupting the fishery. Just say “no” has not been an option—at least not on behalf of the poor Vaquita. Instead, the new leadership at the US Marine Mammal Commission is embracing an “economic incentives strategy,” the kind that has been proven ineffective by every major study—most recently by the World Bank’s report, “Mind, Society, and Behavior.”

Even should such branding of “Vaquita safe shrimp” through better gear be attempted, we know such efforts take years for them to be implemented and fully embraced by fishers, and can have their own unintended consequences on other species. At the current rate, the Vaquita has months, not years. Even by the time our 2007 plan was completed, 58% of the population had been lost, leaving 245 individuals. Today the population is estimated at 97 individuals. Natural population growth for the Vaquita is only about 3 percent a year. And, offsetting this is a sickening rate of decline, estimated at 18.5%, due to human activities.

A Mexican regulatory impact statement issued on December 23, 2014 suggests the ban of gillnet fishing in the region for only two years, full compensation for lost income to fishers, community enforcement, and the hope that there will be an increase in the numbers of Vaquita within 24 months. This statement is a draft government action that is open for public comment, and so we have no idea whether the Mexican government is going to adopt it or not.

Unfortunately, the economics of the illegal Totoaba fishery may doom any plan, even the feeble ones on the table. There are substantiated reports that the Mexican drug cartels are participating in the Totoaba fishery for the export of fish bladders to China. It has even been called the “crack cocaine of fish” because the Totoaba bladders are selling for as much as $8500 per kilogram; and the fish themselves are going for $10,000-$20,000 each in China.

Even if it is adopted, it is not clear that the closure will be enough. To be even marginally effective, there needs to be substantial and meaningful enforcement. Because of the involvement of the cartels, the enforcement probably needs to be by the Mexican Navy. And, the Mexican Navy will have to have the will to interdict and confiscate boats and fishing gear, from fishermen who may be at the mercy of others. However, because of the high value of every fish, the safety and honesty of all enforcers would be put to an extreme test. Yet, it’s unlikely that the Mexican government will welcome outside enforcement assistance.

And frankly, the U.S. is just as culpable in the illicit trade. We have interdicted enough illegal Totoaba (or their bladders) at the U.S.-Mexico border and elsewhere in California to know that LAX or other major airports are likely transshipment points. Action should be taken to make sure that the Chinese government is not complicit in importing this illegally harvested product. This means taking this problem to the level of trade negotiations with China and determining where there are holes in the net that the trade is slipping through.

We should take these steps regardless of the Vaquita and its likely extinction—on behalf of the endangered Totoaba at the very least, and on behalf of a culture of curbing and reducing illegal trade in wildlife, people, and goods. I admit I am heartbroken by our collective failure to implement what we knew about the needs of this unique marine mammal decades ago, when we had the opportunity and the economic and political pressures were less fierce.

I am stunned that anyone clings to the idea that we can develop some “Vaquita-safe shrimp” strategy with just 97 individuals left. I am shocked that North America could let a species come this close to extinction with all the science and knowledge on our hands, and the recent example of the Baiji dolphin to guide us. I want to be hopeful that the poor fishing families get the help they need to replace the income from the shrimp and finfish fishery. I want to be hopeful that we will pull out all the stops to close the gillnet fishery and enforce it against the cartels. I want to believe that we can.

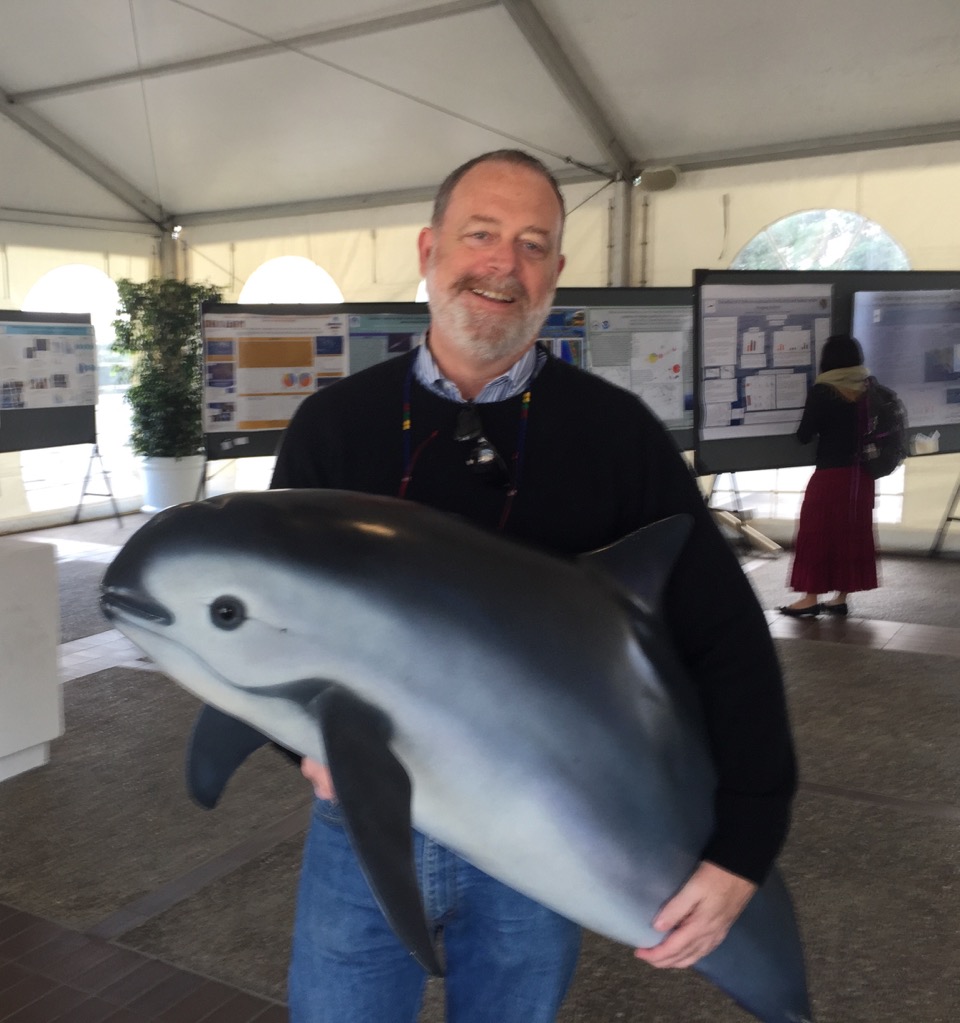

2007 NACEC meeting to produce NACAP on Vaquita

Key image courtesy of Barb Taylor