The ocean is an opaque place in that there is still so much to learn about it. The life patterns of the great whales are also opaque—it is amazing what we still don’t know about these magnificent creatures. What we know is that the ocean is no longer theirs, and in many ways their future looks grim. The last week of September, I played a role in envisioning a more positive future at a three-day meeting about “Stories of the Whale: Past, Present and Future” organized by the Library of Congress and the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

Part of this meeting connected Arctic native peoples (and their connection to whales) to the history of the Yankee whaling tradition in New England. In fact, it went so far as to introduce the descendants of the three whaling captains who had parallel family lives in Massachusetts and Alaska. For the first time, members of three families from Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and New Bedford met their cousins (of the same three families) from communities in Barrow and the north slope of Alaska. I expected this first meeting of parallel families would be a little awkward, but instead they relished the opportunity to look at collections of photos and look for family similarities in the shapes of their ears or noses.

Flight into Nantucket

In looking at the past, we also learned the amazing Civil War story of the CSS Shenandoah campaign against Union merchant whalers in the Bering Sea and Arctic as an attempt to cut off the whale oil that lubricated the North’s industries. The captain of the British-built ship Shenandoah told those he took as prisoners that the Confederacy was in league with the whales against their mortal enemies. No one was killed, and a lot of whales were “saved” by this captain’s actions to disrupt an entire whaling season. Thirty-eight merchant vessels, mostly New Bedford whaleships were captured, and sunk or bonded.

Michael Moore, our colleague from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, noted that present-day subsistence hunts in the Arctic are not supplying the global commercial market. Such hunting is not at the scale of the Yankee whaling era, and is certainly unlike the industrial whaling efforts of the 20th century that managed to kill as many whales in just two years as had an entire 150 years of Yankee whaling.

As part of our three-location meeting, we visited the Wampanoag nation on Martha’s Vineyard. Our hosts provided us with a delicious meal. There, we heard the story of Moshup, a giant man able to catch whales in his bare hands and flail them against the cliffs to provide food for his people. Interestingly, he also foretold the coming of white people and gave his nation the choice of remaining among people, or becoming whales. This is their origin story of the orca who are their relatives.

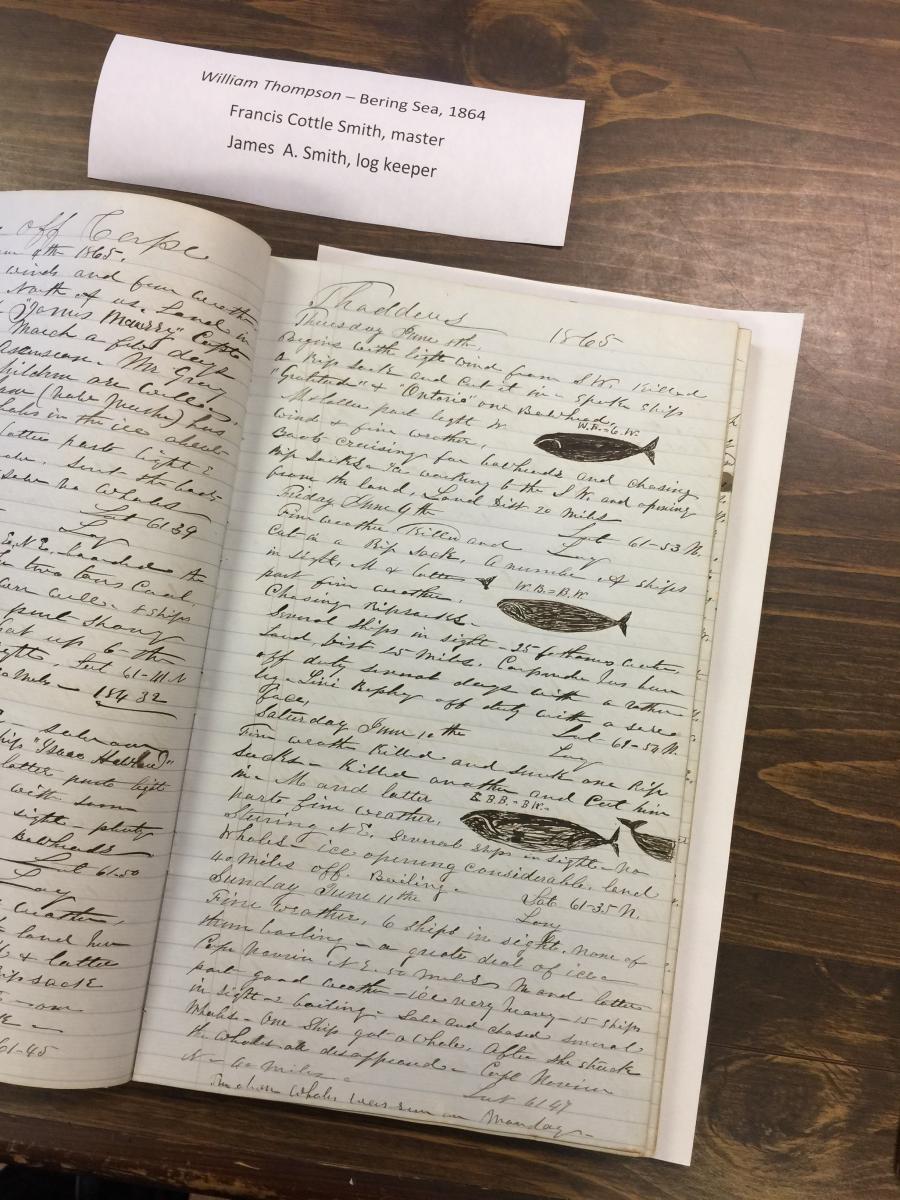

Log book at museum in Marth’s Vineyard

In looking at the present, the workshop participants noted the temperature of the ocean is rising, its chemistry is changing, the ice in the Arctic is receding and the currents are shifting. Those shifts mean that the food supply for marine mammals is also shifting—both geographically and seasonally. We are seeing more marine debris and plastics in the ocean, more acute and chronic noise, as well as significant and frightening bioaccumulation of toxins in sea animals. As a result, whales have to navigate an increasingly busy, noisy and toxic ocean. Other human activities exacerbate their peril. Today we see that they become harmed, or killed by ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements. In fact, a dead endangered northern right whale was found entangled in fishing gear in the Gulf of Maine just as our meeting began. We agreed to support efforts to improve shipping routes and retrieve lost fishing gear and reduce the threat of these slow painful deaths.

Baleen whales, such as right whales, depend on small animals known as sea butterflies (pteropods). These whales have a very specialized mechanism in their mouths in order to filter feed on these animals. These small animals are directly threatened by the change in chemistry in the ocean that makes it harder for them to form their shells, a trend called ocean acidification. In turn, the fear is that whales cannot adapt fast enough to new food sources (if any truly exist), and that they will become animals whose ecosystem can no longer provide them with food.

All of the changes in chemistry, temperature, and food webs make the ocean a significantly less supportive system for these marine animals. Thinking back to the Wampanoag story of Moshup, did those who chose to become orcas make the right choice?

Nantucket Whaling Museum

On the last day as we gathered in the New Bedford whaling museum, I asked this very question during my panel on the future. On one hand, looking at the future, human population growth would indicate an increase in traffic, fishing gear, and the addition of seabed mining, more telecommunications cables, and certainly more aquaculture infrastructure. On the other hand, we can see evidence that we are learning how to reduce noise (quiet ship technology), how to re-route ships to avoid whale population areas, and how to make gear that is less likely to entangle (and as a last resort how to rescue and more successfully disentangle whales). We are doing better research, and better educating people about all the things we can do to reduce harm to whales. And, at the Paris COP last December we finally reached a promising agreement to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, which is the main driver of habitat loss for marine mammals.

It was great to catch up with old colleagues and friends from Alaska, where the changes in climate are affecting every element of daily life and food security. It was amazing to hear the stories, introduce people of common purpose (and even forebears), and watch the beginnings of new connections within the broader community of people who love and live for the ocean. There is hope, and we have a lot we can all do together.