During the summer of 2016, while many of my friends had desk jobs in big cities, traveled to the beach for long weekends, and got their shark thrills via “Shark Week” every summer, I decided to stick to being in school and traded in a desk for the lab. While “Shark Week” is less of a train wreck than it used to be, I prefer real life sharks and real science to the often sensationalized television or movie programs concerning sharks. I’ve focused on sharks for the last few years, working at a shark lab in the Bahamas, and then continuing on to graduate school at Duke University. My summer breaks usually meant field work, lab work, analyzing data, and for one summer: shark guts.

Two summers ago, I spent 3 months really immersed in tiger shark stomachs. And by immersed, I do mean that on many days I was elbow-deep in shark stomachs for hours on end. Other than it being a bit smelly, it was very enjoyable work. Digging around in tiger shark stomachs was the basis of my thesis work. My research aimed to look at what tiger sharks were eating around the northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. I worked with the NOAA Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Panama City, FL, helping out on a Gulf of Mexico Shark Pupping and Nursery Survey, a Smalltooth Sawfish Abundance Survey, and essentially my own research project: tiger shark guts. Throughout the summer I dissected a total of 170 tiger shark stomachs, and it was surprisingly fun.

Tiger shark stomach

Unlike some species of sharks, tiger sharks tend to have a pretty diverse diet. There was a gap in knowledge in the Gulf of Mexico and Northwest Atlantic when it came to quantitatively describing the diet of tiger sharks. Even though these areas are known to contain tiger sharks, there wasn’t a lot of information on their diet, especially a specific breakdown of their diet. Tiger sharks are typically found from New England to the Florida Keys in the Northwest Atlantic and throughout the Gulf of Mexico. Most major studies on tiger shark diet were done in the Pacific and more specifically in Australia and Hawaii. Studies in these areas found that tiger sharks had diverse diets, and consumed everything from dugongs to sea snakes to fish, and many other prey items.

As for other studies done in the Northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico on tiger shark diet, they were usually done in either a very small area, or had a very small sample size, and sometimes both. The studies that I did look at, like one in the Florida Keys, and one done in an area in the central Gulf Coast, both found that tiger sharks had a diverse diet and were eating a number of different prey items. However, I wanted to look at their diet over a larger area, with a bigger sample size, and I wanted to answer a number of questions such as: overall, how is the diet of a tiger shark in this area broken down into prey groups? How important is each prey group to the sharks’ diet? Does the diet change from when sharks are just born to becoming juveniles and then adults? I also looked at how environmental factors might influence diet, how diverse the diet was in each life stage, and if there was an overlap in prey types in each life stage or in each area (Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic).

What are Tiger Sharks Eating?

The purpose of this study is to utilize this information to help inform ecosystem based management. Ecosystem based management is a very broad way to manage something by looking at many interactions that happen within an ecosystem, like the ocean, instead of looking at one specific species or issue. So, to properly manage an area, you have to use information specific to that area. Understanding how tiger sharks interact with their prey is useful, but information on their diet from the Pacific, or information from a very small area within the Atlantic won’t help effectively manage the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

A sea turtle head found in a tiger shark stomach

So, here’s what I did to try to answer some of my research questions and contribute to what we know about tiger sharks in the northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. The number one question I get about my research is whether or not I found any license plates in any of the stomachs (I did not and you’ve been watching too much “Jaws.” But to be fair, license plates have been found in the stomachs of tiger sharks before), or any human remains (I didn’t find those either). The second most popular question I get is “where do you get shark stomachs from?” Sharks were collected from commercial fishermen in the shark bottom longline fishery. This is totally legal, and the stomachs themselves are collected by NOAA observers. Observers collect data at sea while on commercial fishing vessels. The shark is measured, sex is recorded, and the stomachs are removed. Most of the rest of the shark would go to the fishermen. Another portion of my stomachs came from a survey run by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Sharks are caught on a longline, and for the majority of the sharks, their stomachs are everted, meaning you essentially force the shark to regurgitate their stomach contents. The contents are placed in a bag, and the shark is tagged and released. Tiger sharks can regurgitate naturally, and this is not harmful to the shark.

The full stomachs or bags of stomach contents were then sent to the lab, and that’s where I came in. I would prey items as well as I could, essentially trying to identify the species of every item, but at least trying to put each item into a category (e.g. mammal, reptile, etc). Items were counted, measured, weighed, and assigned a level of digestion (e.g. fresh prey, very digested, partially digested, etc). I knew ahead of time what bait was used on the longline, so I would always exclude that. I had help from various members of the NOAA staff identifying some items, especially the fish, and everyone knew when I was coming to ask them about an item because an unmistakable stench gave me away. I was a huge hit during the summer.

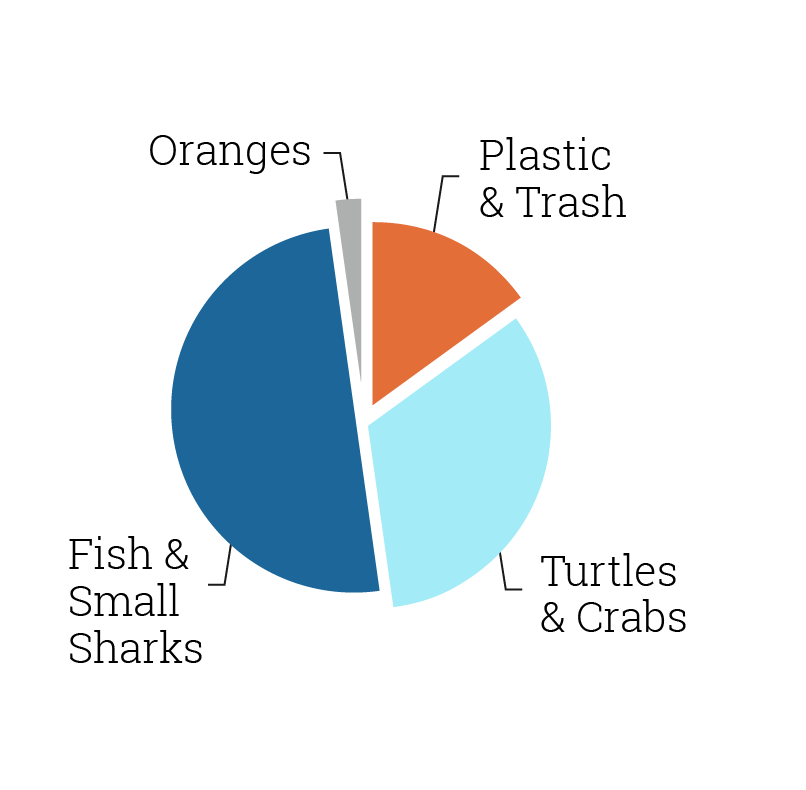

Sharks were captured from North Carolina to Louisiana. Sharks were also broken down into three life stages: young-of-the-year (sharks born within the last year), juveniles, and adults. To break down the diet on a percentage basis, I used information about the number of a certain item, its total weight, and its occurrence (how many total stomachs the item showed up in). This helped me figure out how important an item was to the sharks’ diet. I did this for my major prey categories along with other more specific identifying categories. I had a total of fifteen major prey categories that I identified, including reptiles, mammals, birds, sharks/rays, fish, cephalopods (octopus and squid mainly), arthropods (shrimp and crabs, as examples), trash/rocks, and a number of other categories.

A bird leg found in a stomach

Some of the most interesting items I found were: entire rather large sea turtles that were swallowed completely whole (the tiger shark has some very strong stomach acids), a newborn baby dolphin that looked like an alien and took me forever to figure out what it was (sad, but pretty cool), pieces of an orange that I had to actually smell and peel the rind off to figure out what they were, large vertebrates from other large sharks, sandwich bags and other plastic trash (sad, but also hopefully a wake-up call for anyone who reads this and uses single-use plastics).

My overall findings were that younger tiger sharks were eating more items from the seafloor, along with some fish. Juvenile sharks were eating mostly fish along with a few prey items from the seafloor. Adults ate mostly fish and then some larger prey items, like turtles. I did find that the diet of a tiger shark changed as the shark went from being young to being an adult.

Essentially, as a shark got larger, its prey got larger. This could be because smaller tiger sharks might have trouble catching certain types of prey as well as actually ingesting them. Some of my results were consistent with those of tiger shark diet studies in the Pacific, including that these sharks like to eat many different types of prey, as well as there being a change in diet as sharks get older and larger. However, there were differences in major prey categories for tiger sharks in the Pacific vs. northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, as well as how important the same prey categories were in one place versus the other.

Now we return to the most important question: why do we care about what tiger sharks are eating? Because sharks are at the top of the food chain, they essentially help construct the entire marine community through what they are eating. It is critical to understand this relationship between tiger sharks and what they are eating because this can help us more effectively manage the entire ecosystem. My research was published in a scientific journal, Environmental Biology of Fishes, about six months ago, after I had graduated from Duke. I hope that this information helps inform and improve management of the marine ecosystem as a whole, including tiger sharks, and all of their prey items in the northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

Links/Sources:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10641-017-0706-y

Alex Aines is a former intern of The Ocean Foundation. She is currently a marine scientist at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.