Introduction

The vast blue highways of our global ocean carry nearly 90% of global trade, with massive vessels traversing international waters day and night. While these maritime thoroughfares are essential to our global economy, they also represent potential threats to our ocean ecosystems when accidents occur. At The Ocean Foundation, we closely monitor shipping incidents that threaten marine environments, applying lessons from past disasters to prevent future catastrophes and mitigate environmental damage when they do happen. The recent collision in the North Sea offers a sobering reminder of both our progress and the challenges that remain in protecting our ocean from human-caused disasters.

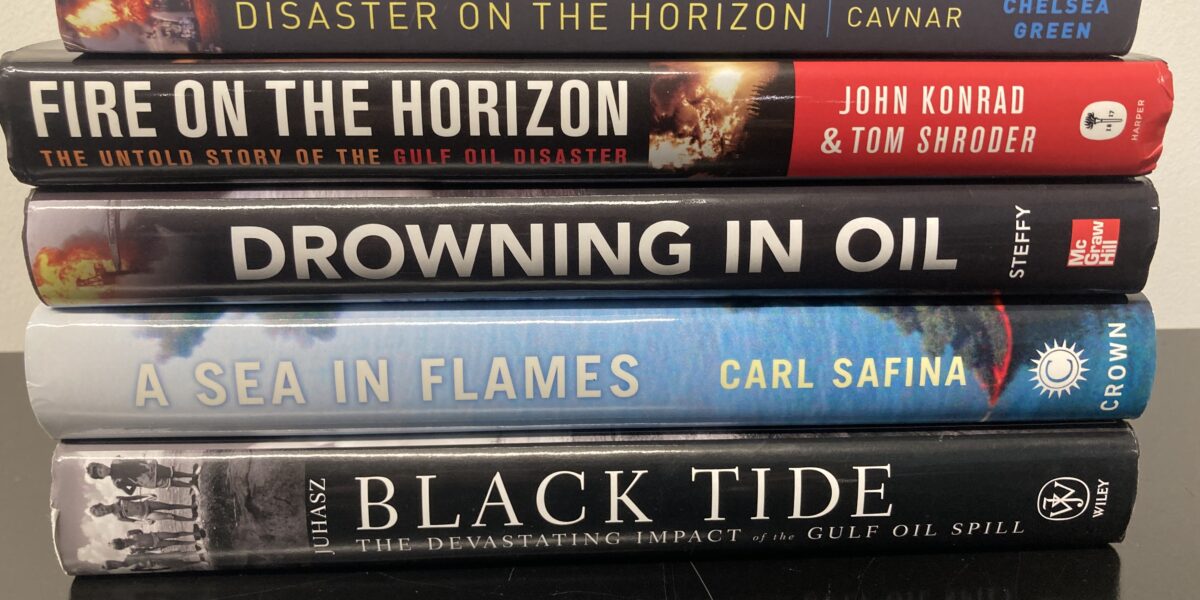

Learning from the Past

Last month, two ships were burning in the North Sea following a collision between the cargo ship Solong and the Stena Immaculate, a tanker carrying at least 220,000 barrels of highly toxic jet fuel when it was struck. The last report suggested that 36 crew members from the two ships have been rescued. Sadly, the remaining crew member has lost his life.

Beyond the tragic human cost, shipping accidents carry the ominous threat of toxic substances leaking into fragile marine ecosystems. Jet fuel evaporates slowly—we’re hopeful that early reports of some burning off and the rest being contained are accurate. Both ships carried bunker fuel to run their engines. Bunker fuel is the general term for heavy fuel oils (HFOs) used to power ships. The fuel is thick and dense and threatens marine life compared to more refined fuels. We learned that lesson from our work on shipping safety following the wreck of the Selendang Ayu in the Aleutians in December of 2004. Limiting the spread of any spilled fuel will be a challenge, especially as the Solong is drifting and smoldering at the last report.

We also know this disaster would have been worse if we hadn’t amended global shipping practices after previous disasters with fuel-carrying vessels. In the late 1990s, larger fuel tankers such as the Stena Immaculate were designed to limit the risk of massive cargo loss and sinking. The ships are double-hulled, and the cargo is divided among multiple smaller tanks to reduce risk even if one or more is breached, as it was on the Immaculate in the collision.

Sometimes, the silver lining of these disasters is better preparation for, and even prevention of, the next one. From our work on the Selendang Ayu, on the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster, and more recently analyzing the risks from potentially polluting wrecks from World War II, we know that hindsight should help establish:

- Better enforcement of workforce and situation monitoring rules on the bridge of cargo ships and tankers, and that includes holding ships until any deficits in radar and other systems are corrected;

- Additional ways to avoid any loss of life in evacuating ships, although it seems as though the speed with which crew members moved to safety helped save their lives;

- Greater capacity to limit and clean up after a collision like this by having enough equipment in place along busy shipping routes and other high-traffic areas and

- Perhaps the most essential ensuring long-term monitoring and assessment of the North Sea or any affected body of water:

a. to enable retrieval of any debris

b. for the presence of remnant chemical and fuel spillage and

c. of sealife for changes in reproductivity, longevity, and general health

Lessons from Deepwater Horizon

The TOF-supported expeditions to assess marine life in the Gulf following the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster emerged as a crucial effort to understand the immediate and long-term impacts on the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. What we discovered was sobering and far-reaching. The main findings of these expeditions include:

Comprehensive Baseline Assessment

The researchers from the Wise Laboratories compiled the first comprehensive baseline of oil contamination across the entirety of the Gulf of Mexico. This involved:

- Sampling over 15,000 fish

- Taking over 2,500 sediment cores

- They initially found high incidences of skin lesions and other abnormalities in fish near the Deepwater Horizon site, which decreased over time.

Fish Population Impacts

- Studies showed a 50 to 80% decrease in deep-water (mesopelagic) fish populations near the blowout site.

- All fish species tested revealed some degree of oil pollution, with no pristine fish found in the system.

- The highest levels of oil exposure were detected in yellowfin tuna, golden tilefish, and red drum.

Marine Oil Snow Sediment and Flocculent Accumulation (MOSSFA)

- Oil attached to suspended planktonic particles settled through the water column and was deposited on the seafloor.

- This accumulation accounted for upwards of 10 percent of the total oil released.

- Biological systems living near or on the seafloor were continuously re-exposed to oil compounds.

Long-term Ecosystem Effects

- Population declines were observed in various species, including oysters, blue crabs, bottlenose dolphins, red snapper, and southern hake.

- Dolphins and other marine life continued to die in record numbers, with infant dolphins dying at six times the normal rate.

- Toxins from oil spills were found to cause irregular heartbeats, leading to cardiac arrest in bluefin tuna and potentially other large predator fish.

- These findings have been crucial in understanding the widespread and lasting impacts of the Deepwater Horizon disaster on the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. They inform ongoing restoration efforts and future oil spill response strategies.

Looking Forward

On a per-unit basis, shipping remains one of the most energy-efficient ways of moving goods worldwide. As shipping evolves to become less polluting and even more efficient, we hope that technology and strong enforcement frameworks reduce the number of at-sea collisions and other accidents. We can also work towards ensuring that when accidents do occur, the damage is minimized through better preparation, response capabilities, and monitoring systems.

Conclusion

The collision in the North Sea and the anniversary of the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster remind us that despite technological advances, our ocean remains vulnerable to sudden environmental disasters. At The Ocean Foundation, we’re committed to immediate response efforts and long-term solutions protecting marine ecosystems from shipping accidents and their aftermath.