On the edge of a far-flung lagoon in Baja California Sur, surrounded by a landscape of low-lying succulents, expansive salt flats, and towering cardón cacti that appear on the horizon as totem-like sentinels enveloped in a mirage, there is a small laboratory. The Francisco “Pachico” Mayoral Field Laboratory.

Inside this laboratory, with its whirring turbine spinning violently on its vertical axis to capture each and every gust, its solar panels glistening like obsidian pools with gridlines bathed in the desert sun, some of the best science in the world on gray whales is being conducted. And, it’s being done by some of the best people in the world to do it.

This is the Laguna San Ignacio Ecosystem Science Program, a project of The Ocean Foundation.

And, this is Laguna San Ignacio, where the desert meets the sea, an otherworldly coastal marine ecosystem, which is part of Mexico’s El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve.

From above, the lagoon seems like an oasis cradled by scarlet and ochre mountains, the vast Pacific Ocean breaking rapturously on the sand bar outlining the lagoon’s entrance. Gazing upward, the infinite pale blue sky transforms every night into a shimmering canopy of stars flowing among the eddies and whirlpools of the Milky Way.

“The visitor to the lagoon must resign himself to the pace of the winds, the tides, and in doing so, all the wonder of the place becomes accessible. This annual transition in attitude and perception, a slowing of daily life to follow more natural clocks, developing a full appreciation of what each day brought us, for better or worse, is what we came to call ‘Lagoon Time.'” – Steven Swartz (1)

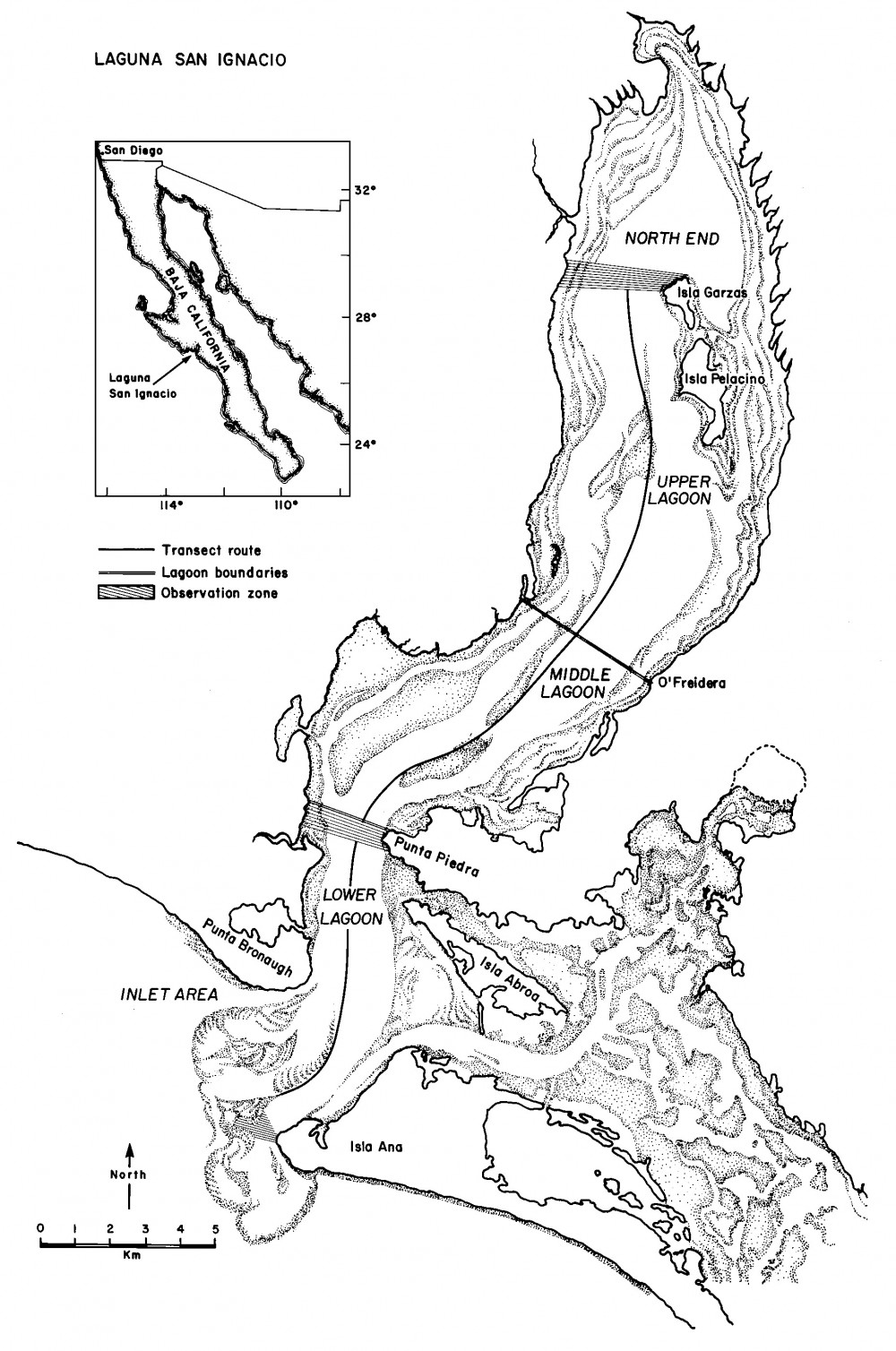

Steven Swartz and Mary Lou Jones’ original hand-drawn map

When I first arrived at night on its inky black shores following a 4×4 trek across the desert, the wind blowing hard and loud—as it often does—and filled with desert grit and salt, I could faintly make out a noise emanating from the darkness before me. As I focused upon the sound, my other senses were muted. The flapping tents housing students and scientists were suspended mid-billow; the stars receded into a stellar froth, their dull white pallor seeming to coat the sound and give it synesthetic definition. And, then, I knew the origin of the noise.

It was the sound of gray whale blows—mothers and calves—echoing sonorously across the horizon, the whoosh enshrouded by the cavernous darkness, stained with mystery, and revealing of new life.

The Program looks at “indicators”—biological, ecological, and even sociological metrics—to monitor and provide recommendations to ensure the ongoing health of the Laguna San Ignacio Wetlands Complex. The data collected by LSIESP, viewed in the context of larger scale environmental changes resulting from global warming, is very useful for long-term planning to ensure this unique ecosystem can sustain external pressures from eco-tourism, fishing, and the people who call this place home. Uninterrupted datasets have helped shaped our understanding of the lagoon, its stressors, its cycles, and the nature of its seasonal and permanent inhabitants. In conjunction with historical baseline data, the continued efforts by LSIESP has made this one of the most studied places for observing gray whale behavior in the world.

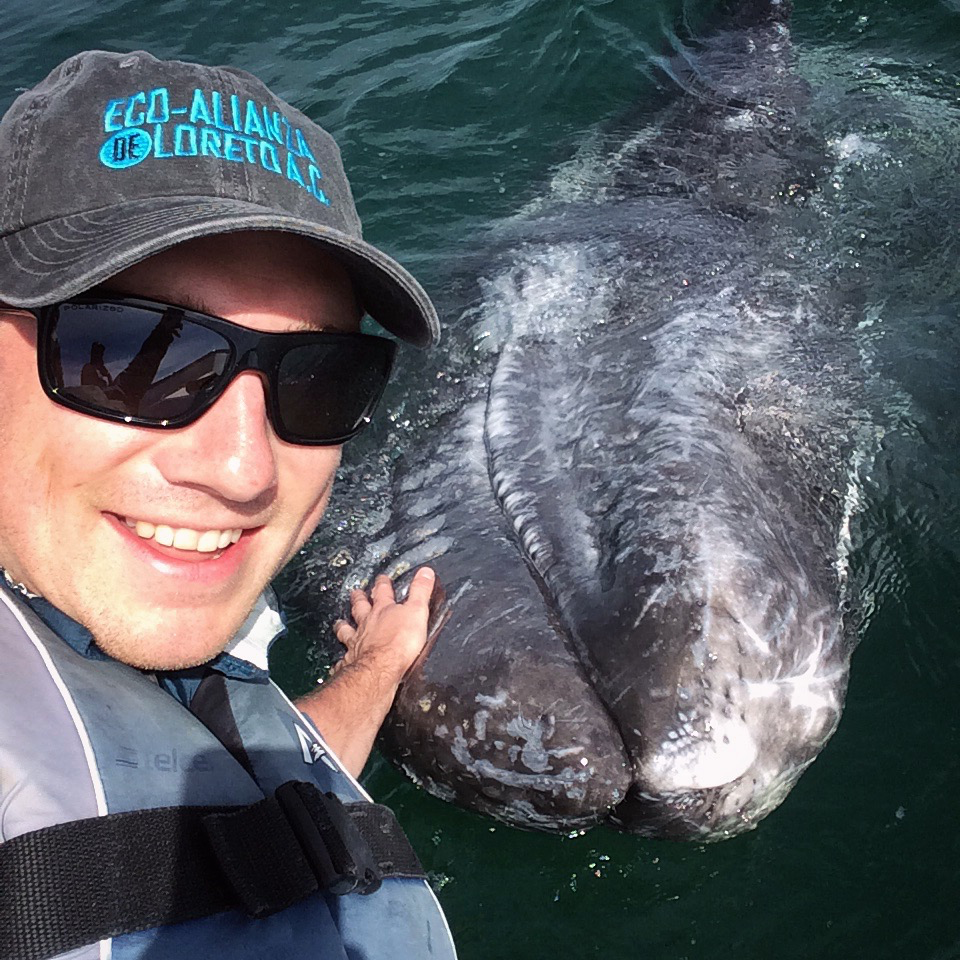

One helpful tool that has emerged in the last few decades is digital photography. Once a task that required extensive amounts of film, toxic chemicals, dark rooms, and a keen eye for comparison, now researchers can take hundreds if not thousands of photographs on a single outing to capture the perfect shot for comparative purposes. Computers aid in the analysis of photographs by allowing for rapid review, assessment, and permanent storage. As a result of digital cameras, photo-identification has become a mainstay of wildlife biology and allows LSIESP to participate in the monitoring of the health, physical condition, and lifetime growth of individual gray whales in the lagoon.

LSIESP and its researchers have been publishing reports of their findings since the early 1980’s with photo-identification serving a critical role. In the latest field report for the 2015-2016 season, the researches note: “Photographs of ‘re-captured’ whales confirmed female whale ages ranging from 26 to 46 years, and that these females are continuing to reproduce and visit Laguna San Ignacio with their new calves each winter. These are the oldest photographic identification data for any living gray whales, and clearly demonstrate the fidelity of breeding female gray whales to Laguna San Ignacio.” (3)

Long-term, uninterrupted datasets have enabled LSIESP’s researchers to correlate gray whale behavior with large-scale environmental conditions including El Niño y La Niña cycles, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, and sea surface temperatures. The presence of these events has a discernible impact on the timing of gray whale arrival and departure each winter, as well as the number of whales and their overall health.

New genetic research is allowing researchers to compare the gray whales of Laguna San Ignacio with the critically endangered population of Western gray whales, which occupy the opposite side of the Pacific basin. Through partnerships with other institutions around the world, LSIESP has become a key node in a vast-ranging monitoring network dedicated to better understanding the ecology and range of gray whales worldwide. Recent sightings of gray whales off the coast of Israel and Namibia suggest that their range may be expanding as climate change opens up ice-free corridors in the Arctic to allow for the movement of whales back into the Atlantic—an ocean they have not occupied since going extinct during the height of commercial whaling.

LSIESP is also expanding its avian research to explore the critical role birds play in the lagoon’s complex ecosystem, as well as their relative abundance and behavior. After suffering a devastating loss of ground-nesting birds on Isla Garza and Isla Pelicano to hungry coyotes, who have proved to be either very adept at monitoring the tides or simply really good swimmers, artificial posts have been installed around the lagoon to help populations rebuild.

Perhaps one of the most important functions of the program is educational. LSIESP provides opportunities for learning by involving students—primary school through college—and exposing them to scientific research methods, conservation best practices, and, above all, a majestic, unique ecosystem which not only hosts life—it inspires life.

Back in March, the program hosted a class from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur, a key partner of LSIESP. During the field trip, students participated in field exercises, which mirror the work done by the program’s researchers, including photo identification of gray whales and avian surveys to estimate bird abundance and diversity. Speaking with the group at the end of their trip, we discussed the variety of opportunities available to support this critical work, and the importance of experiencing the lagoon firsthand. While not all of the students will go on to become wildlife biologists working in the field, it is clear that this sort of engagement is not only fostering awareness—it is creating a new generation of stewards to ensure the lagoon’s continued protection far into the future.

Drawing in around 125 guests, including tourists, students, researchers, and local residents, the Community Reunion demonstrates LSIESP’s commitment to the dissemination of reliable scientific information and creating a space for dialogue with the many stakeholders that utilize the lagoon. Through forums like this, the program educates and empowers the local community to make informed decisions about future development options.

This sort of community engagement has proved essential in the wake of the Mexican government’s decision to cancel a controversial plan in the late 1990s to build an industrial scale solar salt production facility at the lagoon, which would have severely altered the ecosystem. By engaging local residents, LSIESP has provided data to support the sustainable development of a thriving eco-tourism industry that depends on the preservation of the lagoon’s unique flora and fauna. Ongoing conservation efforts create an economic return on investment given the importance of maintaining the pristine appeal of the lagoon’s ecosystem to continue to attract tourists who support the livelihoods of local residents.

What does the future hold for this special place? In addition to the uncertainty associated with the impacts on the ecosystem resulting from global climate change, economic development is progressing at the lagoon. While the road to the lagoon is certainly no bustling thoroughfare, there are concerns that increased access resulting from the road’s snaking advance of pavement will increase pressure on this delicate landscape. Plans to bring electrical service and water from the town of San Ignacio will greatly improve the quality of life for local residents, but it is unclear whether this arid landscape can support additional permanent habitation while preserving its unique quality and abundance of wildlife.

Whatever may happen in the years to come, it is clear that the ongoing protection of Laguna San Ignacio will largely depend, as it has in the past, on the area’s most iconic visitors, la ballena gris.

“Ultimately gray whales are their own ambassadors for goodwill. Few people who encounter these primeval leviathans leave unchanged. No other animals in Mexico are capable of eliciting the type of support that gray whales have. Consequently, these cetaceans will shape their own future.” – Serge Dedina (4)

(1) Swartz, Steven (2014). Lagoon Time. The Ocean Foundation. San Diego, CA. 1st edition. Page 5.

(2) Laguna San Ignacio Ecosystem Science Program (2016). “About.” http://www.sanignaciograywhales.org/about/.

(3) Laguna San Ignacio Ecosystem Science Program (2016). 2016 Research Report for Laguna San Ignacio & Bahia Magdalena. 2016 http://www.sanignaciograywhales.org/2016/06/2016-research-reports-new-findings/

(4) Dedina, Serge (2000). Saving the Gray Whale: People, Politics, and Conservation in Baja California. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. 1st edition.