Dirty fingernails, scuffed knees, grass stains, hot sun. Everyone remembers days like these playing outside as a kid. Like most people, my view of nature and connection to the environment is shaped by my place-based childhood experiences. I did not grow up near or even have access to beaches or an ocean coastline. I grew up in a landlocked state in mid-America.

Despite my lack of accessibility to the ocean, I still feel a strong relationship with our waters through my connection with America’s veins: our rivers. My family lives outside of Louisville, Kentucky in a small riverside community on the Ohio River. Similar to that of ocean communities, the river ecology is interwoven with the history, culture, and livelihood of the surrounding people.

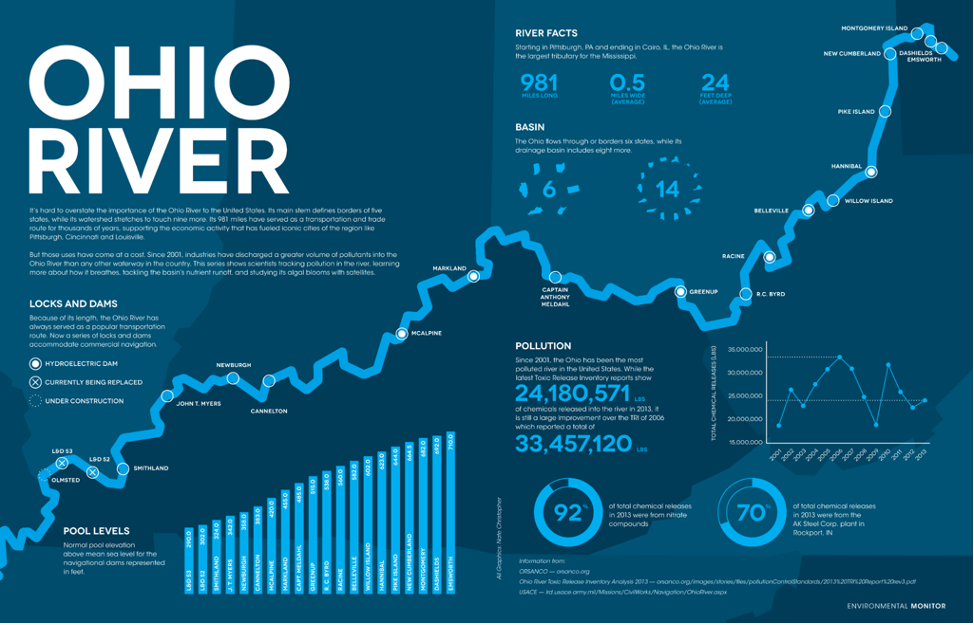

Its passage through my family’s yard is only a few hundred feet. But the Ohio River stretches 981 miles (1,579 km) across the eastern United States. It is the largest tributary by volume of the Mississippi River. The river flows through my home state of Kentucky and five other states, and its watershed is in one of the most populated and industrialized regions, encompassing 14 U.S. states.

Along with myself, more than 25 million people live in the Ohio river basin. And 5 million of us use the river as our main source of drinking water. Meanwhile, the river continues to serve other purposes for our surrounding communities, powering 38 energy facilities and transporting 184 million tons of cargo each year (most of which is coal). Our community’s lifeline is the river and the numerous benefits it provides.

Like the rest of the United States, the Ohio River valley existed and thrived long before the white man’s discovery in the 1700’s.

Its valley was cultivated and cared for by Native inhabitants including Lenape, Erie, Shawnee, Munsee, Susquehannock, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Yuichi, and Iroquois. The Seneca gave its name, “ohiyo” which means “beautiful river.” The river witnessed the eradication and removal of its Native caretakers in the valley.

Before and during the Civil War, the Ohio River served as part of the border that divided free states and enslaved states. The river became known as “River Jordan ” by the enslaved people making their journey to freedom north across the Ohio River. More people crossed the Ohio River to freedom than anywhere else on the north-south border.

I feel at ease on and by the water, although my view does not include an ocean horizon. I have vivid memories as a child of the full green river landscape. A foggy morning sky covering a river of glass, clear with the reflection of the surrounding trees. A sunset, silently painting the sky and its river reflection with pastels only to quickly slip into darkness.

As much as I continue to romanticize my perspective of the river as beautiful, I am faced with the sad reality of what pollution has done to the river. For every memory I hold of a foggy river morning or pastel sunset, I hold another memory of washed-up plastic, discarded trash, and a lingering fear of the invisible chemical pollution. Many of the threats to our oceans begin on land and in our rivers. Saving our oceans also means cleaning our rivers, including the Ohio.

The Ohio River is no stranger to pollution.

Since the enactment of the Clean Water Act in 1972, the water looks and smells less like the open dumping ground it was treated as. But, the remaining water quality issues remain more challenging as they are often invisible. In 2015, the U.S. The Environmental Protection Agency named the Ohio River one of the country’s most polluted rivers for the seventh year in a row. It continues to be at the top of many pollution lists. Industrial chemicals, including those coined as “Forever Chemicals,” perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) are to blame for the majority of the toxic waste. The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO), founded to control and abate pollution in the Ohio River Basin, reported 23 million pounds of toxic discharge (Cory, 2015).

The river is victim to the pollution of industrial plants, barges, sewage waste, agricultural runoff, and general urban pollution. A report by the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) stated that of the 23 million pounds of toxic discharge, over 70 percent can be attributed to the A.K. Steel plant located in Rockport, Indiana (Cory, 2015). Although many other industries are at fault for contamination, they can easily use water dilution to ensure their toxic release levels remain at an acceptable percentage.

Federal regulation could be better enforced or even amended to reduce river pollution.

ORSANCO and its eight member states can take great strides towards a clean Ohio River system. But they are currently failing to do so. In 2019, ORSANCO voted to make its current regional water pollution standards voluntary rather than mandatory to its member states. Rather than regulating pollutants, ORSANCO is focusing its efforts on only monitoring and research. They do however continue to host “River Sweeps,” which are annual volunteer clean-ups along the Ohio River. These sweeps help clean up the visible, namely plastic litter that lines the river shoreline. But, they do nothing to stop pollution at its sources.

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) have become a more frequent occurrence in lagoons, lakes, and coastal areas. Excess nutrients, including fertilizers, sewage, and other sources of nitrogen and phosphorous, have caused such blooms, especially where average water temperatures are rising. Until recently, HABs were uncommon in the mostly fast-moving waters of the Ohio River. That is changing. Climate change effects such as increased temperatures and varying precipitation increase the risks for algal bloom occurrences.

In 2015, such a bloom persisted from August to September, covering over 600 miles of the Ohio River with blue-green toxic algal goop (Velzer, 2019). Similarly, in 2019, drought-like conditions and warm weather caused algal blooms to grow sporadically along a 300-mile stretch of the Ohio River (Saenz, 2019).

The more nutrient pollution and runoff in our waterways, the more blooms, especially in low water, high-temperature conditions.

Harmful algal blooms greatly affect water quality by depleting oxygen on which fish and other animals depend. Blue-Green blooms like those identified in the Ohio River and its tributaries produce cyanotoxins that can make humans and animals ill. For humans, harmful algal blooms are public health hazards, causing skin irritation, liver disease, neurological problems, and serious respiratory distress.

For animals, the blooms produce toxins that can kill fish, dogs, and farm animals that are exposed. Dense blooms prevent light from reaching aquatic plants growing on the bottom, which suppresses their growth or kills them. When blooms begin to die, the breakdown process depletes the oxygen supply in the water, resulting in the loss of aquatic life that is dependent on oxygen for survival. Blue-green algae have been around for millions of years, but the frequency, duration, and intensity of blooms have increased due to human activities. The way to prevent such threatening disturbances is to eliminate pollution at the source so that it never ends up in our water systems.

Like air, water moves.

All of the pollution that is contaminating our Ohio River is not contained by it. Rather, it continues to flow down into the Mississippi River, eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. Nutrient contaminants running from the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico exacerbate water quality challenges faced by coastal communities. The infamous “dead zone” of the Gulf of Mexico has its roots in my home river. So here, 1000 miles from the Gulf, what we do matters.

Photo Credit: EPA

The problems of nutrient runoff, toxic chemical contamination, harmful algal blooms, and plastic pollution are challenges for ALL water systems. Not just in the Ohio river, not just in America, but everywhere. Yet, our water systems are our interconnected lifelines. And without clean, healthy water, human and ecosystem health is in danger. To maintain a healthy, viable ocean, we must also protect our rivers. Only with collaboration and interconnected efforts will we be able to protect our waters for future generations.

As someone who has watched the river flow for the past twenty years, I am consistently reminded of its threats and its beauty.

Like many people, I believe that the environment and ecology of my home are worth protecting for their innate beauty alone. I hold boundless gratitude for the experiences I have had with nature and the river. It’s the endless memories of the muddy shore walks, the evening riverboat rides, and the dogs playing fetch in the water that illustrates the personal value of our rivers and why so many of us strive to protect our water systems. Together, we must tell our decision-makers how much we value our connectivity. We must work collaboratively to protect our rivers, so that all children of the future have access to clean and healthy waters and to an abundant ocean.

Kitty Helm | The Munson Foundation, Senior Research Intern

Works Cited

Cory, C. (2015, November 24). Environmental Protection Agency CALLS Ohio River the Most Polluted in Country. The News Record. https://www.newsrecord.org/news/environmental-protection-agency-calls-ohio-river-the-most-polluted-in-country/article_5d6a04a6-9304-11e5-bf5c-c70efe02bafb.html.

Saenz, E. (2019, September 30). IDEM warns of harmful algal blooms in Ohio River. Indiana Environmental Reporter. https://indianaenvironmentalreporter.org/posts/idem-warns-of-harmful-algal-blooms-in-ohio-river.

Velzer, R. V. (2019, October 22). Toxic Algal BLOOMS Persist In Ohio River, but They’re in Decline. 89.3 WFPL News Louisville. https://wfpl.org/toxic-algal-blooms-persist-in-ohio-river-but-theyre-in-decline/.