Deep seabed mining (DSM) is a potential commercial industry attempting to mine mineral deposits from the seafloor, in the hopes of extracting commercially valuable minerals such as manganese, copper, cobalt, zinc, and rare earth metals. However, this mining is posed to destroy a thriving and interconnected ecosystem that hosts a staggering array of biodiversity: the deep ocean.

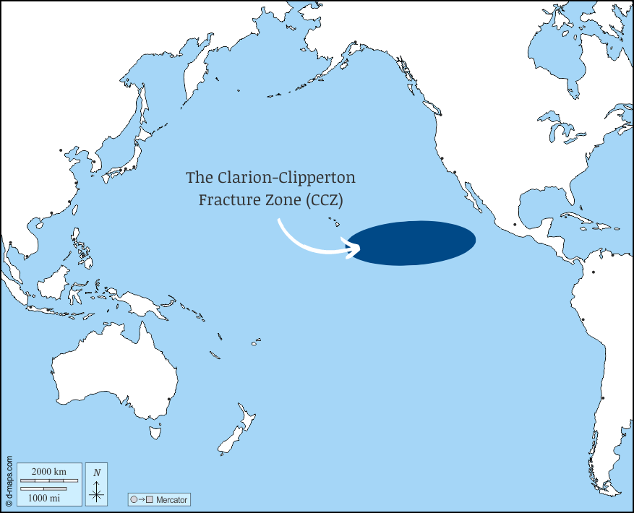

The mineral deposits of interest are found in three habitats located on the seafloor: the abyssal plains, seamounts, and hydrothermal vents. Abyssal plains are vast expanses of the deep seabed floor covered in sediment and mineral deposits, also called polymetallic nodules. These are the current primary target of DSM, with attention focused on the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ): a region of abyssal plains as wide as the continental United States, located in international waters and spanning from the west coast of Mexico to the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just south of the Hawaiian Islands.

Danger to the Seabed and the Ocean Above It

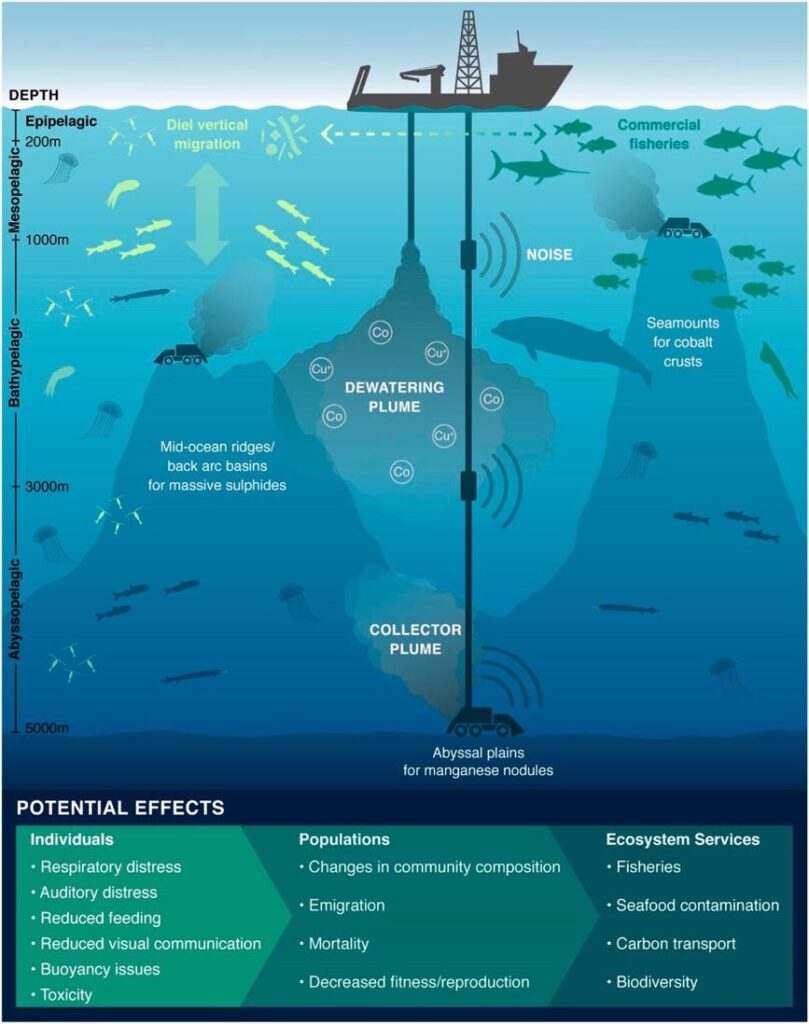

Commercial DSM has not started, but various companies are trying to make it a reality. Current proposed methods of nodule mining include the deployment of a mining vehicle, typically a very large machine resembling a three-story tall tractor, to the seafloor. Once on the seabed, the vehicle will vacuum the top four inches of the seabed, sending the sediment, rocks, crushed animals, and nodules up to a vessel waiting on the surface. On the ship, the minerals are sorted and the remaining wastewater slurry (a mix of sediment, water, and processing agents) is returned to the ocean via a discharge plume.

DSM is anticipated to impact all levels of the ocean, from physical mining and churning of the ocean floor, to dumping of waste into the midwater column, to spilling of potentially toxic slurry at the ocean surface. The risks to deep sea ecosystems, marine life, underwater cultural heritage, and the entire water column from DSM are varied and serious.

Studies indicate deep seabed mining will cause an unavoidable net loss of biodiversity, and have found a net zero impact is unattainable. A simulation of the anticipated physical impacts from seabed mining was conducted off the coast of Peru in the 1980s. When the site was revisited in 2015, the area showed little evidence of recovery.

There is also Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) at risk. Recent studies demonstrate a wide variety of underwater cultural heritage in the Pacific Ocean and within the proposed mining regions, including artifacts and natural environments related to Indigenous cultural heritage, the Manila Galleon trade, and World War II.

The mesopelagic, or midwater column, will also feel the impacts of DSM. Sediment plumes (also known as underwater dust storms), as well as noise and light pollution, will affect much of the water column. Sediment plumes, both from the mining vehicle and post-extraction wastewater, could spread 1,400 kilometers in multiple directions. Wastewater containing metals and toxins may affect midwater ecosystems as well as fisheries..

The “Twilight Zone”, another name for the ocean’s mesopelagic zone, falls between 200 and 1,000 meters below sea level. This zone contains more than 90% of the biosphere, supporting commercial and food-security relevant fisheries including tuna in the CCZ area slated for mining. Researchers have found that the drifting sediment will affect a wide variety of underwater habitats and marine life, causing physiological stress to deep sea corals. Studies are also raising red flags about the noise pollution caused by mining machinery, and indicate that a variety of cetaceans, including endangered species like blue whales, are at high risk for negative impacts.

In Fall 2022, The Metals Company Inc. (TMC) released sediment slurry directly into the ocean during a collector test. Very little is known about the impacts of the slurry once returned to the ocean, including what metals and processing agents might be mixed in the slurry, if it would be toxic, and what effects it would have on the various marine animals and organisms that live within the layers of the ocean. These unknown impacts of such a slurry spill highlight one area of the significant knowledge gaps that exist, affecting the ability of policymakers to create informed environmental baselines and thresholds for DSM.

Governance and Regulation

The ocean and the seabed are governed primarily by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an international agreement that determines the relationship between States and the ocean. Under UNCLOS, each country is ensured jurisdiction, i.e. national control, over the use and protection of – and resources contained within – the first 200 nautical miles out to sea from the coastline. In addition to UNCLOS, the international community agreed in March 2023 to a historic treaty on the governance of these regions outside of national jurisdiction (called the High Seas Treaty or treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction “BBNJ”).

The regions outside the first 200 nautical miles are better known as Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction and often called the “high seas”. The seabed and subsoil in the high seas, also known as “the Area,” is specifically governed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an independent organization established under UNCLOS.

Since the ISA’s creation in 1994, the organization and its Member States (the member countries) have been tasked with creating rules and regulations surrounding the protection, exploration, and exploitation of the seabed. While exploration and research regulations exist, the development of extractive mining and exploitation regulations long remained unhurried.

In June 2021, the Pacific island state Nauru triggered a provision of UNCLOS which Nauru believes requires mining regulations to be completed by July 2023, or the approval of commercial mining contracts even without regulations. Many ISA Member States and Observers have spoken out that this provision (sometimes called the “two-year rule”) does not oblige the ISA to authorize mining.

Many states do not consider themselves bound to greenlight mining exploration, according to publicly available submissions for a March 2023 dialogue where countries discussed their rights and responsibilities related to approval of a mining contract. Nonetheless, TMC continues to tell concerned investors (as late as March 23, 2023) that the ISA is required to approve their mining application, and that the ISA is on track to do so in 2024.

Transparency, Justice, and Human Rights

Prospective miners tell the public that to decarbonize, we must pillage the land or the sea, often comparing the negative effects of DSM to terrestrial mining. There is no indication that DSM would replace terrestrial mining. In fact, there is much evidence that it would not. Therefore, DSM would not alleviate human rights and ecosystems concerns on land.

No terrestrial mining interests have agreed or offered to close or scale back their operations if someone else makes money mining minerals from the seabed. A study commissioned by the ISA itself found that DSM would not cause overproduction of minerals globally. Scholars have contended that DSM could end up exacerbating terrestrial mining and its many problems. The concern is, in part, that a “slight decline in prices” could drive down safety and environmental management standards in land-based mining. Despite a buoyant public facade, even TMC admits (to the SEC, but not on their website) that “[i]t may also not be possible to definitively say whether the impact of nodule collection on global biodiversity will be less significant than those estimated for land-based mining.”

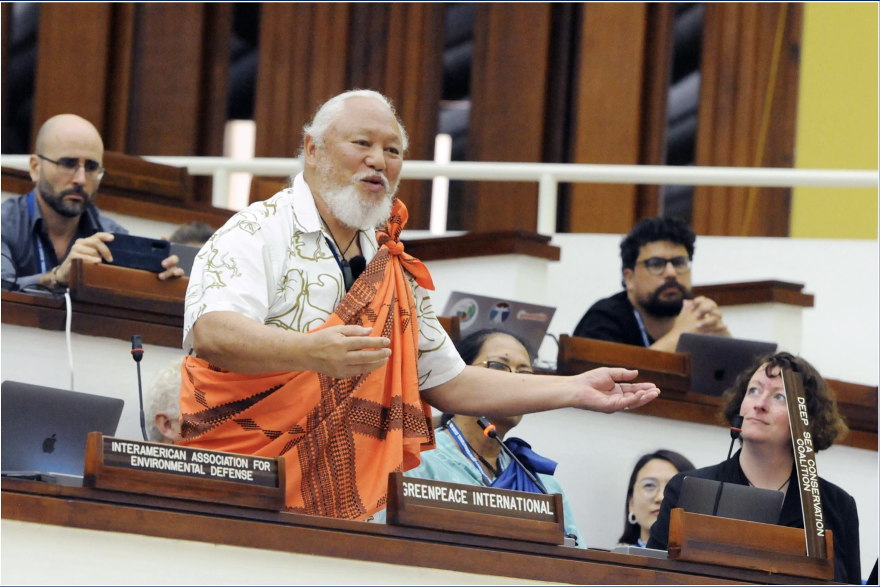

According to UNCLOS, the seabed and its mineral resources are the common heritage of humankind, and belong to the global community. As a result, the international community and all connected to the world ocean are stakeholders in the seabed and the regulation that governs it. Potentially destroying the seabed and the biodiversity of both the seabed and the mesopelagic zone is a major human rights and food security concern. So is the lack of inclusion in the ISA process for all stakeholders, with particular regards to Indigenous voices and those with cultural connections to the seabed, youth, and a diverse group of environmental organizations including environmental human rights defenders.

DSM proposes additional risks to tangible and intangible UCH, and may cause destruction of historic and cultural sites that are important to people and cultural groups around the world. Navigation pathways, lost shipwrecks from World War II and the Middle Passage, and human remains are scattered far and wide in the ocean. These artifacts are part of our shared human history and are at risk of being lost before being found from unregulated DSM.

Youth and Indigenous peoples around the world are speaking out to protect the deep seabed from extractive exploitation. The Sustainable Ocean Alliance has successfully engaged youth leaders, and Pacific Island Indigenous people and local communities are raising their voices in support of protecting the deep ocean. At the 28th Session of the International Seabed Authority in March 2023, Pacific Indigenous leaders called for the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the discussions.

Calls for a Moratorium

The 2022 United Nations Ocean Conference saw a large push for a DSM moratorium, with international leaders like Emmanuel Macron supporting the call. Businesses including Google, BMW Group, Samsung SDI, and Patagonia, have signed onto a statement by the World Wildlife Fund supporting a moratorium. These companies agree to not source minerals from the deep ocean, to not finance DSM, and to exclude these minerals from their supply chains. This strong acceptance for a moratorium in the business and development sector indicates a trend away from the use of the materials found on the seabed in batteries and electronics. TMC has admitted that DSM may not even be profitable, because they cannot confirm the quality of the metals and – by the time they are extracted – they may not be needed.

DSM is not necessary to transition away from fossil fuels. It is not a smart and sustainable investment. And, it will not result in the equitable distribution of benefits. The mark left on the ocean by DSM will not be brief.

The Ocean Foundation is working with a diverse array of partners, from boardrooms to bonfires, to counter false narratives about DSM. TOF also supports increasing stakeholder involvement at all levels of the conversation, and a DSM moratorium. The ISA is meeting now in March (follow our intern Maddie Warner on our Instagram as she covers the meetings!) and again in July – and perhaps October 2023. And TOF will be there alongside other stakeholders working to protect the common heritage of humankind.

Want to learn more about deep seabed mining (DSM)?

Check out our newly updated research page to get started.