By Mark J. Spalding, President

Ten years ago this month, the weather along the Great Circle Route in the North Pacific was horrible. Then again, the weather in this part of the world is frequently horrible, and hazardous to shipping. The Malaysian-registered bulk carrier Selendang Ayu was carrying a load of soybeans and making her way along the Great Circle Route when she lost power, broke in half in heavy seas, and ran partially aground in the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. Unalaska Community Broadcasting’s Annie Ropiek did a great piece last week on the continuing ramifications of this spill. http://kucb.org/news/article/10-years-on-selendang-ayu-spills-legacy-still-evolving/

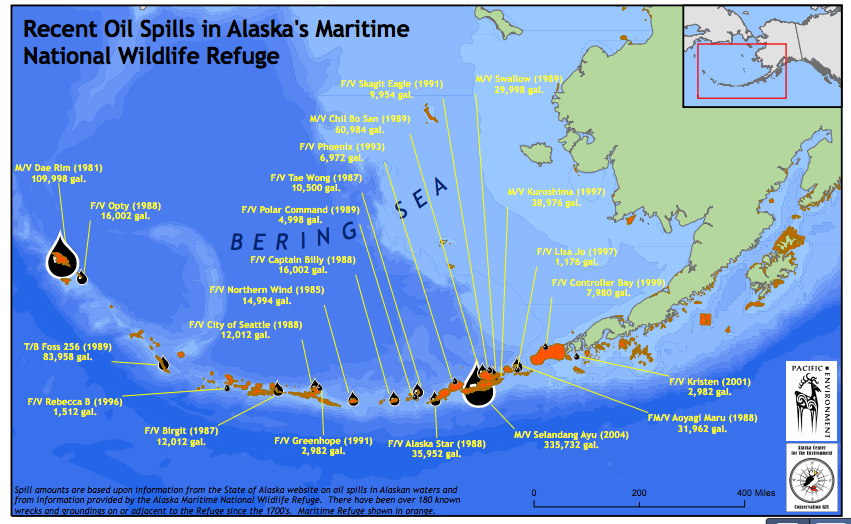

According to the National Wildlife Service, today’s Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge includes lands that were formerly parts of ten previously established refuges. Because it is spread out along most of the 47,300 miles of Alaska’s coastline, the sheer span of this refuge is difficult to grasp. Traveling between its farthest-flung points would be the equivalent of taking a trip from Georgia to California. Alaska Maritime’s seashore lands provide nesting habitat for approximately 40 million seabirds, or about 80% of Alaska’s nesting seabird population. No other maritime National Wildlife Refuge in America is as large or as productive, and yet, its delicately balanced ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to harm from maritime accidents.

When the Selendang Ayu accident occurred, there was no heavy duty tug nearby that could handle a ship that size. The two smaller tugs that were on the scene could not hold her. The Coast Guard arrived to rescue the crew by helicopter, but tragically six men lost their lives—an event that inspired the movie “The Guardian.” The Selendang Ayu was a disaster in another way. When the ship broke apart, she lost her cargo and her fuel—dumped into the sensitive coastal habitat of the Aleutian Islands. All told more than 65,000 tons of soybeans spilled and smothered the ocean floor. So too did more than 350,000 gallons of bunker fuel oil—the heaviest and dirtiest fuel that can be spilled. As Ropiek’s article points out, the clean-up took years and remains incomplete, at best.

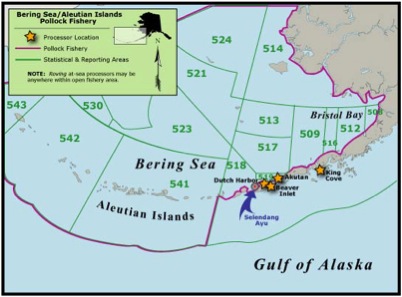

The Shipping Safety Partnership (SSP) was formed in collaboration with the Alaska Oceans Program and The Ocean Foundation in the wake of this disaster, the third large spill in the Aleutian maritime refuge. The Partnership included native community groups, fishing groups, and local, national and international environmental groups, including the Petroleum Environment Network of China. Our collective goal was to advocate for better safety practices, more equipment resources, and improved communication requirements for ships in the Great Circle Route, and beyond. Even as the SSP held its first meetings and developed its suite of recommendations, two more significant shipping accidents occurred in the refuge, although the harm was not as great. TOF Board of Advisors member Rick Steiner has continued to push for adoption of the SSP’s recommendations ever since they were formalized in a 2005 report.

The SSP recommendations acknowledged the importance of shipping and the ways in which it could be improved for the safety of fisheries and other resources that are also important to human well-being. Briefly, the SSP asked for the following in addition to new funding via a cargo fee on transiting vessels:

1. Aleutian Islands Vessel Traffic Risk Assessment – commissioned by government agencies, and executed by independent parties, the assessment would include (1) a full description of all vessel traffic along the cargo route through the Aleutian Islands, (2) a complete history of maritime accidents and where the risks seem to be the greatest; and (3) an assessment of what kinds of risk reduction measures might be most effective.

2. Establishment and requirement of real-time vessel tracking system for all large vessels – using Automatic Identification System (AIS) (or other technology as appropriate) – and continuous tracking of all vessels by US Coast Guard.

3. Stationing three rescue / salvage tugs along the Aleutian traffic route – at least 10,000 hp—capable of connecting a tow line and rendering a save to any disabled vessel in the majority of sea conditions anywhere along the route. There should be one at Dutch Harbor / Unimak, one at Adak, and one at Shemya.

4. Possibility of emergency tow packages to be required on all large merchant vessels (as required on tankers by IMO) – to aid in the connection of a tow line in emergencies.

5. Communication protocols / agreements between USCG / vessel owners / operators requiring all vessel masters to immediately radio the USCG tracking center (Rescue Coordination Center – Juneau?) when / if any situation arises that could lead to a casualty.

6. Improved spill response capability along the Aleutian route – booms, lightering capability, skimmers, pumps, barges / bladders, training / contracting of local residents in spill response, etc.

7. Alternative transits further from shore—in instances where these large vessels transit near sensitive habitats, requesting future transits to move further offshore to allow more sea room to mitigate potential casualties and, possibility of weather restrictions for transiting Unimak Pass, and other areas of particular concern.

8. Agreement with all shippers to seek to minimize invasive species introductions from shipping, including via ballast water discharge, invasive seeds in cargo, rats, etc. as soon as possible.

9. Potential improvement of vessel construction standards, e.g. improved hull strength, redundant propulsion/ steerage, protected full tanks, etc.

Globally shipping is expanding as more and more markets become interdependent for resources and finished products. In many ways, shipping can be a very efficient and effective way to move goods, with minimal harm to the ocean environment. We at TOF continue to support efforts to ensure that we make common sense choices in the face of known risks to the resources on which so many communities depend. The 10th anniversary of the Selendang Ayu coincides with the tragic tanker spill in the Sunderbans, which I wrote about last week—both should serve as a reminder to devote resources and make good choices before the worst of the problems arise. Prevention is much easier than cleaning up and restoring our productive coastal systems—and full recovery takes more than a generation—time and resources we can choose not to lose.

photos taken by Forrest R Bowers, ADFG. Dutch Harbor

Map courtesy of Pacific Environment