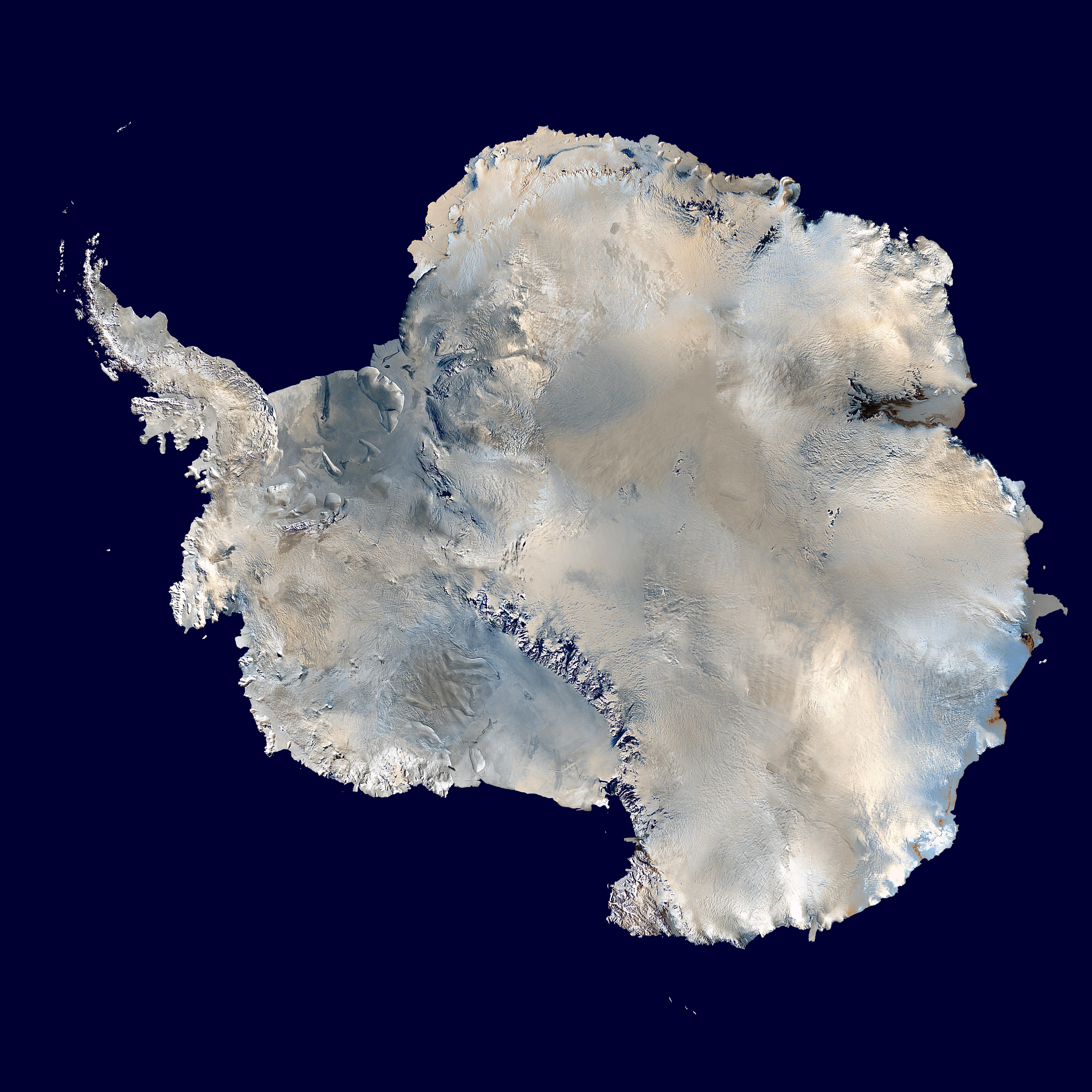

Claire Christian is the Acting Executive Director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), our friendly office neighbors here in DC and out in the global ocean.

This past May, I attended the 39th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM), an annual meeting for the countries that have signed the Antarctic Treaty to make decisions about how Antarctica is governed. To those who don’t participate in them, international diplomatic meetings often seem mind-bogglingly slow. It simply takes time for multiple nations to agree on how to approach an issue. At times, however, the ATCM has made rapid and bold decisions, and this year was the 25th anniversary of one of the 20th century’s biggest wins for the global environment – the decision to ban mining in Antarctica.

While the ban has been celebrated since it was agreed to in 1991, many have expressed skepticism that it could last. Presumably, human rapacity would win out eventually and it would be too hard to ignore the potential for new economic opportunities. But at this year’s ATCM, the 29 decision-making countries that are party to the Antarctic Treaty (called Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties or ATCPs) unanimously agreed to a resolution stating their “firm commitment to retain and continue to implement…as a matter of highest priority” the ban on mining activities in the Antarctic, which is part of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (also called the Madrid Protocol). While affirming support for an existing ban may not seem like an achievement, I believe it is a strong testament to the strength of the commitment of ATCPs to preserving Antarctica as a common space for all humankind.

While affirming support for an existing ban may not seem like an achievement, I believe it is a strong testament to the strength of the commitment of ATCPs to preserving Antarctica as a common space for all humankind.

The history of how the mining ban came to be is a surprising one. ATCPs spent over a decade negotiating the terms for mining regulation, which would take the form of a new treaty, the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA). These negotiations prompted the environmental community to organize the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) to argue for the creation of World Park Antarctica, where mining would be prohibited. Nevertheless, ASOC followed CRAMRA negotiations closely. They, along with some ATCPs, were not supportive of mining but wanted to make the regulations as strong as possible.

When CRAMRA discussions finally concluded, all that remained was for ATCPs to sign it. Everyone had to sign for the agreement to enter into force. In a surprising turnaround, Australia and France, both of whom had worked on CRAMRA for years, announced they would not sign because even well-regulated mining presented too great a risk to Antarctica. One short year later, those same ATCPs negotiated the Environment Protocol instead. The Protocol not only banned mining but set out rules for non-extractive activities as well as a process for designating specially protected areas. Part of the Protocol describes a process for review of the agreement fifty years from its entry into force (2048) if requested by a country Party to the Treaty, and a series of specific steps for lifting the mining ban, including ratification of a binding legal regime to govern extractive activities.

It would not be inaccurate to say that the Protocol revolutionized the Antarctic Treaty System.

It would not be inaccurate to say that the Protocol revolutionized the Antarctic Treaty System. Parties began to focus on environmental protection to a much greater degree than they had previously. Antarctic research stations began examining their operations to improve their environmental impact, particularly with respect to waste disposal. The ATCM created a Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) to ensure implementation of the Protocol and to review environmental impact assessments (EIA) for proposed new activities. At the same time, the Treaty System has grown, adding new ATCPs such as the Czech Republic and Ukraine. Today, many countries are justifiably proud of their stewardship of the Antarctic environment and their decision to protect the continent.

Despite this strong record, there are still rumblings in the media that many ATCPs are merely waiting for the clock to run down on the Protocol review period so they can access the purported treasure below the ice. Some even proclaim that the 1959 Antarctic Treaty or the Protocol “expires” in 2048, an entirely inaccurate statement. This year’s resolution helps reaffirm that ATCPs understand that the risk to the fragile white continent is too great to allow even highly regulated mining. Antarctica’s unique status as a continent exclusively for peace and science is far more valuable to the world than its potential mineral riches. It’s easy to be cynical about national motivations and assume that countries only act in their own narrow interests. Antarctica is one example of how nations can unite in the common interests of the world.

Antarctica is one example of how nations can unite in the common interests of the world.

Still, in this anniversary year, it is important to celebrate achievements and to look towards the future. The mining ban alone will not preserve Antarctica. Climate change threatens to destabilize the continent’s massive ice sheets, altering local and global ecosystems alike. Furthermore, the participants in the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting could take greater advantage of the provisions of the Protocol to enhance environmental protection. In particular they could and should designate a comprehensive network of protected areas that would protect biodiversity and help address some of the effects of climate change on the region’s resources. Scientists have described current Antarctic protected areas as “inadequate, unrepresentative, and at risk” (1), meaning they do not go far enough in supporting that which is our most unique continent.

As we celebrate 25 years of peace, science, and unspoiled wilderness in Antarctica, I hope the Antarctic Treaty System and the rest of the world will take action to ensure another quarter century of stability and thriving ecosystems on our polar continent.