I have been afraid of this day for a long time, the “lessons learned” postmortem panel: “Conservation, controversy and courage in the Upper Gulf of California: fighting the vaquita vortex”

My heart was aching as I listened to my friends and long-time colleagues, Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho1 and Frances Gulland2, their voices breaking at the podium reporting the lessons learned from the failure of efforts to save the Vaquita. They, as part of the international recovery team3, and many others have tried so hard to save this small unique porpoise found only in the northern part of the Gulf of California.

In Lorenzo’s talk, he mentioned the good, the bad and the ugly of the Vaquita story. This community, the marine mammal biologists and ecologists did outstanding science, including developing revolutionary ways to use acoustics to count these endangered porpoises and define their range. Early on, they established that the Vaquita were in decline because they were drowning while entangled in fishing nets. Thus, the science also established that the seemingly simple solution was to stop the fishing with that gear in Vaquita habitat—a solution proposed when the Vaquita still numbered over 500.

The bad is the Mexican government’s failure to actually protect the Vaquita and its sanctuary. A decades-long unwillingness to act to save the Vaquita by fishing authorities (and the national government) meant failing to mitigate the by-catch and failing to keep shrimp fishers out of the Vaquita sanctuary, and failing stop illegal fishing of the endangered Totoaba, whose float bladders are sold on the black market. The lack of political will is a central part of this story, and thus a central culprit.

The ugly, is the story of corruption and greed. We cannot ignore the more recent role of the drug cartels in trafficking the float bladders of the Totoaba fish, paying fishermen to break the law, and threatening enforcement agencies up to and including the Mexican Navy. This corruption extended to government officers and individual fishers. It is true the wildlife trafficking is something of more recent development, and thus, it does not give an excuse for the lack of political will to manage a protected area to ensure that it actually provides protection.

The coming extinction of the Vaquita is not about ecology and biology, it is about the bad and the ugly. It is about poverty and corruption. Science is not enough to enforce the application of what we know to the saving of a species.

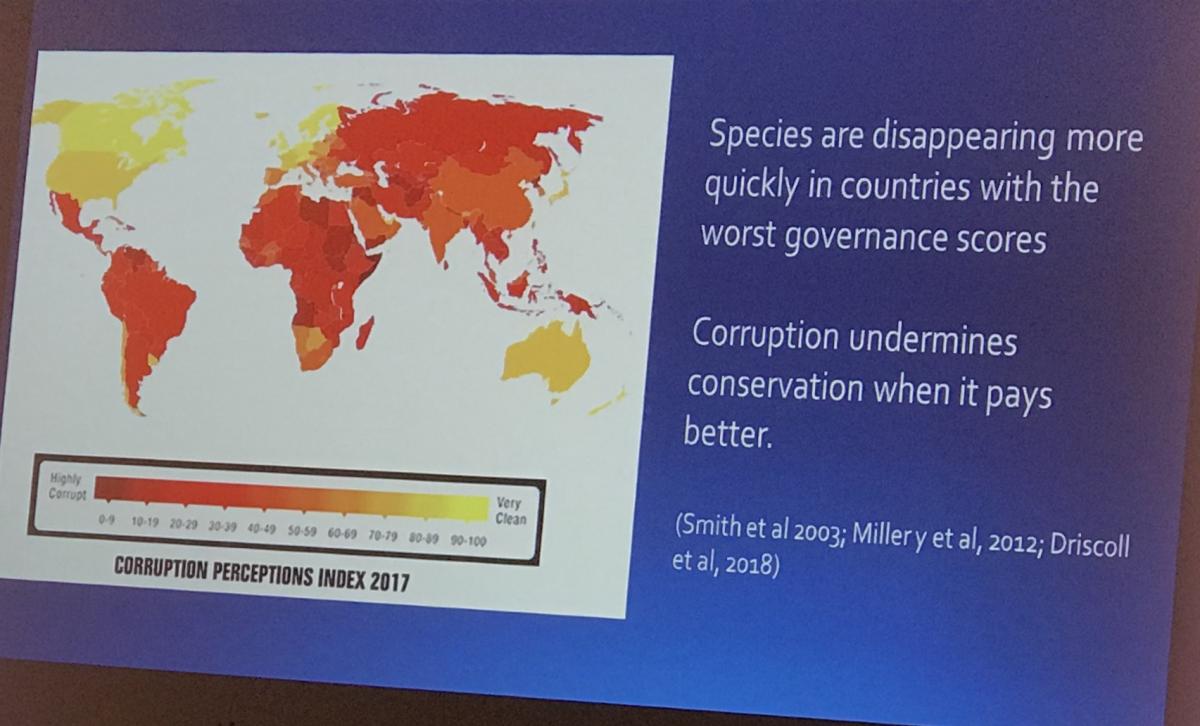

And we are looking at a sorry list of the next species at risk of extinction. In one slide, Lorenzo showed a map that overlapped global poverty and corruption ratings with endangered small cetaceans. If we have any hope of saving the next of these animals, and the next, we have to figure out how to address both poverty and corruption.

In 2017, a photo was taken of the president of Mexico (whose powers are extensive), Carlos Slim, one of the richest men in the world, and box office star and dedicated conservationist Leonardo DiCaprio as they committed to help save the Vaquita, which at the time numbered about 30 animals, down from 250 in 2010. It didn’t happen, they couldn’t bring together the money, the communications reach, and the political will to overcome the bad and the ugly.

As we well know, the trafficking of rare and endangered animal parts often leads us to China and the globally protected Totoaba is no exception. US authorities have intercepted hundreds of pounds of swim bladders worth tens of millions of US dollars as they were smuggled across the border to be flown across the Pacific. At first, the government of China was not cooperative in addressing the Vaquita and Totoaba float bladder issue because one of its citizens had been denied the opportunity to build a resort in another protected area further south in the Gulf of California. However, the Chinese government has arrested and prosecuted its citizens who are part of the illegal Totoaba trafficking mafia. Mexico, sadly, has not prosecuted anyone, ever.

So, who comes in to deal with the bad and the ugly? My specialty, and why I was invited to this meeting4 is to talk about the sustainability of financing marine protected areas (MPAs), including those for marine mammals (MMPAs). We know that well-managed protected areas on land or at sea support economic activity as well as species protection. Part of our concern is that there is already insufficient funding for science and management, thus it is hard to imagine how to finance dealing with the bad and the ugly.

What does it cost? Who do you fund to create good governance, political will, and to thwart corruption? How do we generate the will to enforce the many existing laws so that the cost of illegal activities is greater than their revenue and thus generated more incentives to pursue legal economic activities?

There is precedence for doing so and we are clearly going to need to link it to MPAs and MMPAs. If we are willing to challenge trafficking in wildlife and animal parts, as part of the fight against trafficking in humans, drugs and guns, we need to make a direct link to the role of MPAs as one tool in disrupting such trafficking. We will have to raise the importance of creating and ensuring MPAs are effective as a tool to prevent such trafficking if they are going to be adequately funded to play such a disrupting role.

In her talk, Dr. Frances Gulland carefully described the agonizing choice to attempt to capture some Vaquitas and keep them in captivity, something that is anathema to nearly everyone who works on marine mammal protected areas and against marine mammal captivity for display (including her).

The first young calf became very anxious and was released. The calf has not been seen since, nor reported dead. The second animal, an adult female, also rapidly began to show significant signs of anxiety and was released. She immediately turned 180° and swam back into the arms of those who released her and died. A necropsy revealed that the estimated 20-year-old female had a heart attack. This ended the last-ditch effort to save the Vaquita. And thus, a very few humans have ever touched one of these porpoises while they were alive.

The Vaquita is not yet extinct, no formal statement will come for some time. However, what we do know is that the Vaquita may be doomed. Humans have helped species recover from very small numbers, but those species (such as the California Condor) were able to be bred in captivity and released (see box). The extinction of the Totoaba is also likely—this unique fish was already threatened by overfishing and the loss of freshwater inflow from the Colorado River due to diversion from human activities.

I know that my friends and colleagues who took up this work never gave up. They are heroes. Many of them have had their lives threatened by the narcos, and the fishermen corrupted by them. Giving up was not an option for them, and it should not be an option for any of us. We know that the Vaquita and the Totoaba, and every other species depend on humans to address the threats to their very existence that humans have created. We must strive to generate the collective will to translate what we know into the protection and recovery of species; that we can globally accept the responsibility for the consequences of human greed; and that we can all participate in efforts to promote the good, and punish the bad and the ugly.

1 Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Mexico

2 Marine Mammal Center, USA

3 CIRVA—Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita

4 The 5th International Congress on Marine Mammal Protected Areas, in Costa Navarino, Greece