By Miranda Ossolinski

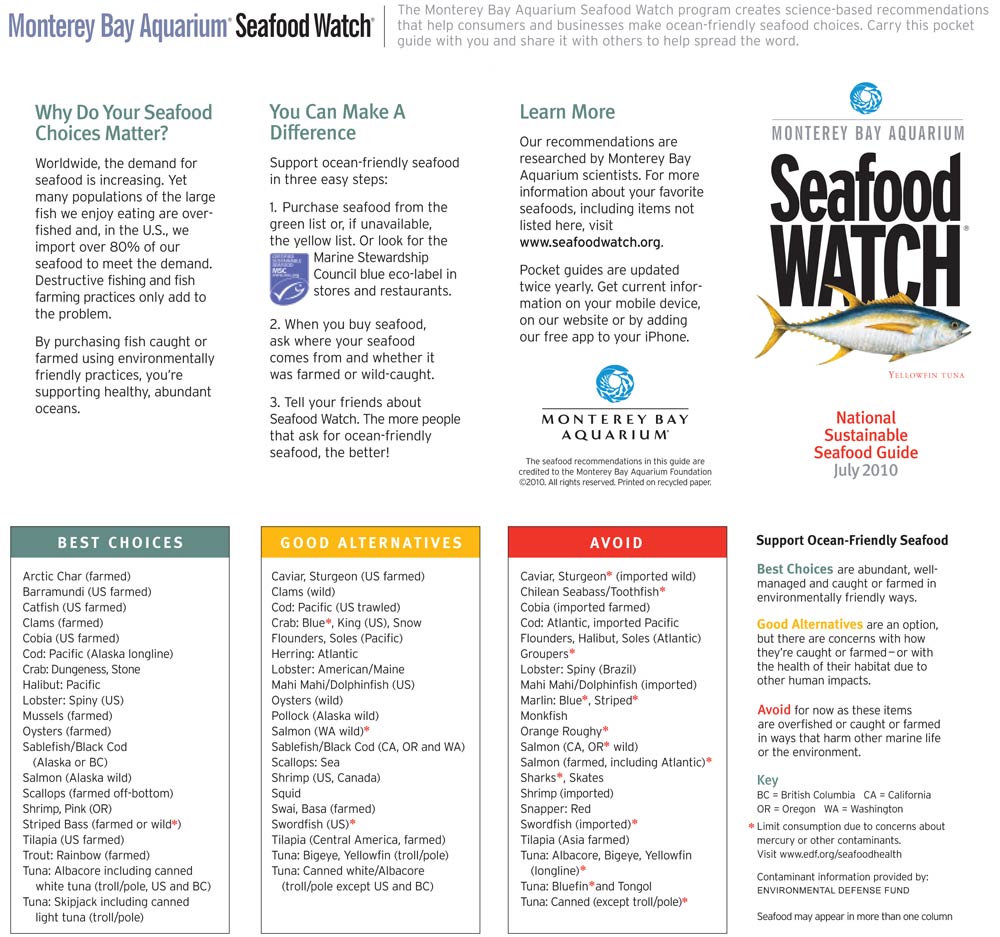

I have to admit that I knew more about research than about ocean conservation issues when I first started interning at The Ocean Foundation during the summer of 2009. However, it didn’t take long before I was imparting ocean conservation wisdom to others. I started educating my family and friends, encouraging them to buy wild instead of farmed salmon, convincing my dad to cut down on his tuna consumption, and pulling out my Seafood Watch pocket guide in restaurants and grocery stores.

During my second summer at TOF, I dove into a research project on “ecolabeling” in partnership with the Environmental Law Institute. With the growing popularity of products labeled as “environmentally friendly” or “green,” it seemed increasingly important to look more closely at the specific standards required of a product before it received an ecolabel from an individual entity. To date, there is no single government-sponsored ecolabel standard related to fish or products from the ocean. However, there are a number of private ecolabel efforts (e.g. Marine Stewardship Council) and seafood sustainability assessments (e.g. those created by Monterey Bay Aquarium or Blue Ocean Institute) to inform consumer choice and promote better practices for fish harvest or production.

My job was to look at multiple ecolabeling standards to inform what might be appropriate standards for third party certification of seafood. With so many products being ecolabled, it was interesting to find out what those labels were actually saying about the products they certified.

One of the standards I reviewed in my research was Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). LCA is a process that inventories all the material and energy inputs and outputs within each stage of a product’s life cycle. Also known as a “cradle to grave methodology,” LCA attempts to give the most accurate and comprehensive measurement of a product’s impact on the environment. Thus, LCA can be incorporated into the standards set for an ecolabel.

Green Seal is one of many labels that has certified all kinds of every day products, from recycled printer paper to liquid hand soap. Green Seal is one of the few major ecolabels that incorporated LCA into its product certification process. Its certification process included a period of Life Cycle Assessment Study followed by the implementation of an action plan to reduce life cycle impacts based on the study’s results. Because of these criteria, Green Seal meets the standards set out by the ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) and the US Environmental Protection Agency. It became clear throughout the course of my research that even standards have to meet standards.

Despite the intricacies of so many standards within standards, I came to better understand the certification process of products that carry an ecolabel like Green Seal. Green Seal’s label is has three levels of certification (bronze, silver, and gold). Each builds upon the other sequentially, so that all products at the gold level must also meet the requirements of the bronze and silver levels. LCA is part of each level and includes requirements for reducing or eliminating impacts from the raw material sourcing, the manufacturing process, the packaging materials, as well as product transport, use, and disposal.

Thus, if one were looking to certify a fish product, one would need to look at where the fish was caught and how (or where it was farmed and how). From there, using LCA might involve how far it was transported for processing, how it was processed, how it was shipped, the known impact of producing and using the packaging materials (e.g. Styrofoam and plastic wrap), and so on, right through to the consumer’s purchase and disposal of waste. For farmed fish, one would also look at the kind of feed used, the sources of feed, the use of antibiotics and other drugs, and the treatment of effluent from the farm’s facilities.

Learning about LCA helped me better understand the complexities behind measuring impact on the environment, even on a personal level. Although I know that I have a damaging effect on the environment through the products I buy, the food I consume, and the things I throw away, it is often a struggle to see how significant that impact really is. With a “cradle to grave” perspective, it is easier to comprehend the real extent of that impact and understand that the things I use do not begin and end with me. It encourages me to be aware of how far my impact goes, to make efforts to reduce it, and to keep carrying my Seafood Watch pocket guide!

Former TOF research intern Miranda Ossolinski is a 2012 graduate of Fordham University where she double majored in Spanish and Theology. She spent the spring of her junior year studying in Chile. She recently completed a six-month internship in Manhattan with PCI Media Impact, an NGO that specializes in Entertainment Education and communications for social change. She is now working in advertising in New York.