A Statement by The Ocean Foundation’s Mark J. Spalding

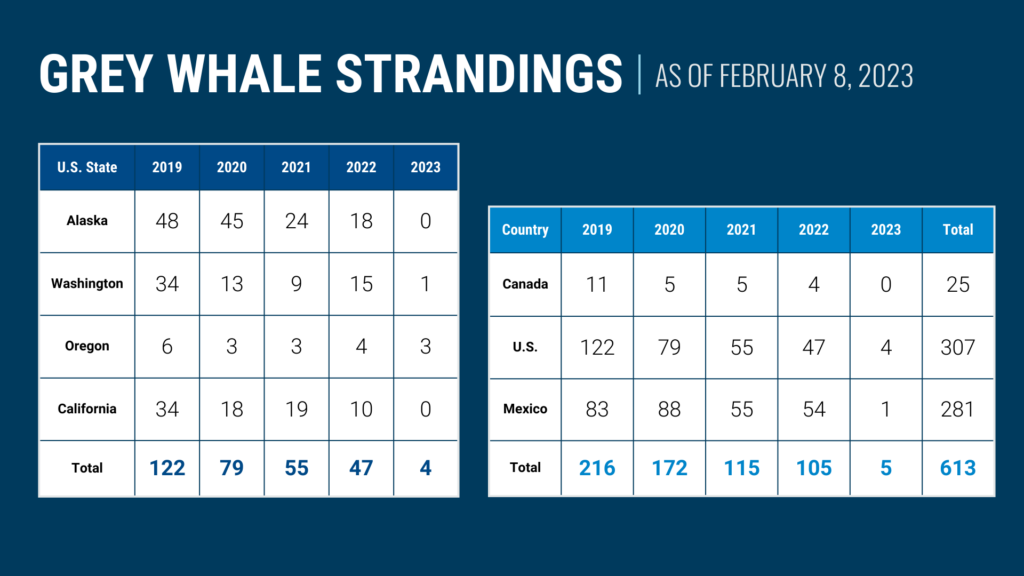

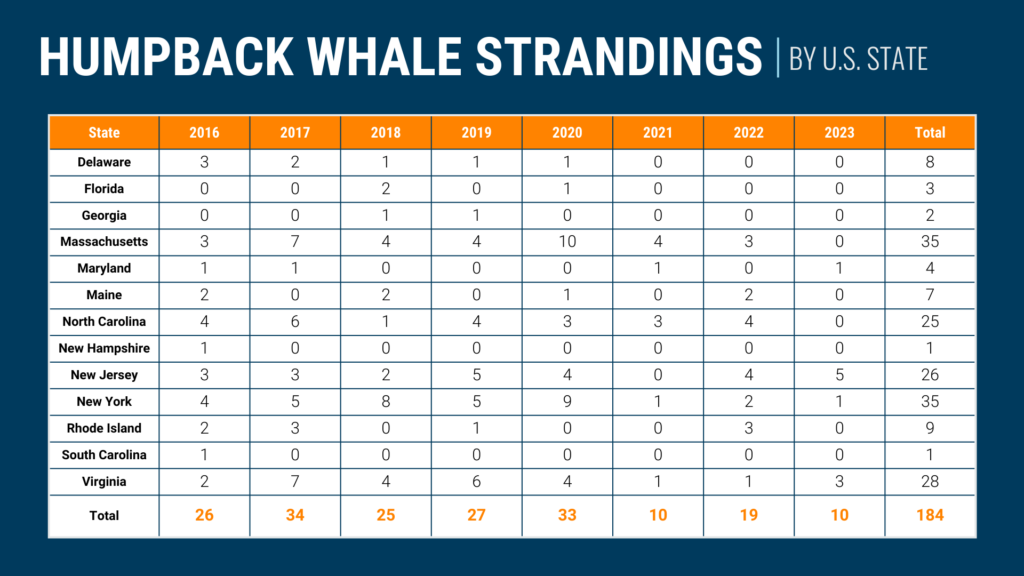

People are right to be concerned about the number of sperm and humpback whales that have stranded on Atlantic beaches from Maine to Florida. Minke whales are also dying at unusual rates. People are also justifiably concerned about the more than 600 Pacific gray whales that have stranded over the past four years on beaches in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. Equally concerned are the scientists and other experts at the Marine Mammal Commission, as well as NOAA Fisheries, the responsible division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Sadly, the recent spate of humpback whale and minke whale strandings is just another phase of the lengthy “Unusual Mortality Event” or UME, a formal designation that must be made using criteria prescribed by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. For east coast humpback whales, this UME began in 2016!

So, what does it mean to have a mortality event that has stretched over seven years? What’s causing it?

Scientists from government agencies and research institutions are striving to figure that out. Not all dead whales can be properly evaluated—often because decomposition is too advanced by the time they are located. However, almost half of the necropsies on the stranded whales show evidence of ship strikes or entanglements. In addition, there are unknown factors such as the impact of toxic algae blooms on food supplies and viruses and other infectious diseases that have had a role in the mortality of marine mammals in previous UMEs.

Obviously, we as an ocean conservation community can take steps to ensure that ocean-going vessels of all sizes are abiding by NOAA’s precautionary speed and other guidelines to reduce the potential for hitting a whale. The science supports slowing down smaller boats (35 to 64 feet) to meet the same longstanding requirements for vessels over 64 feet. Last fall, NOAA’s proposal to do just that met sharp opposition from the owners of those smaller vessels.

We can continue to remove ghost gear and require technical improvements to fishing gear to prevent entanglements. After all, we just lost one of the remaining Atlantic right whales to entanglement in Canadian fishing gear. If at least 40% of untimely future whale deaths can be prevented by these things that can be controlled, we should ensure that happens.

We can invest in the research that would give us far more accurate data about how many humpbacks are currently in U.S. Atlantic waters for all or part of the year. We can investigate the causes of unusual sperm whale strandings that have occurred in other parts of the world. We can ensure that the Marine Mammal Stranding Network organizations have the financial and human resources they need to respond quickly and perform the necessary sampling and analysis for toxins or other markers.

We also have a responsibility to ensure that there is no rush to judgment as to other causes based on conjecture rather than evidence. It is true that the ocean is very noisy because of human activities. Yet shipping is one of the most climate-friendly ways to move goods and materials—and the industry is being pressured to be cleaner, quieter, and more efficient. Offshore wind offers great promise as a clean source of electric power—and the industry is under pressure to be as clean and quiet as possible.

“High-intensity noise, like the seismic blasting that the oil and gas industry uses to prospect deep under the seafloor, can disturb marine mammals, fish, and other species over large areas of ocean, and noise from commercial shipping has created a constant din. But the sounds produced by offshore wind’s pre-construction surveys are much lower in energy than more powerful industrial sources, and tend to be highly directional, making it very unlikely that they drove the whales off New York and New Jersey to strand.”

Francine Kershaw and Alison Chase, NRDC

What is important is that ANY human activity in the ocean needs to be monitored for negative effects on the health of the ocean and the life within. The rules that govern those activities must be crafted and enforced with the well-being of marine life as the top priority. With the proper investment in research and enforcement, we can reduce the causes of whale mortality that we understand and can prevent. And we can pursue solutions for the whale deaths we don’t yet understand.