The International Seabed Authority’s third set of meetings held in Kingston, Jamaica, wrapped up last week with little fanfare and fewer decisions.

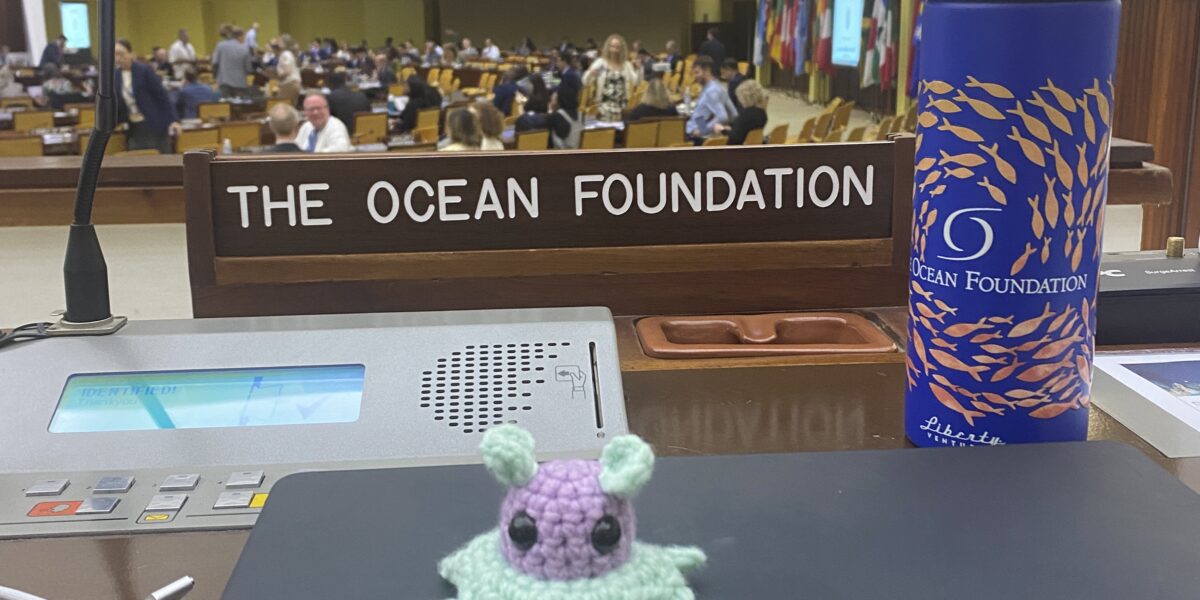

(Photo by Nicole Zaneszco)

The Ocean Foundation participated in the meetings for the third time this year, continuing to speak with delegates on our key goals:

1. Ensuring the inclusion and consideration for the protection of all Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH)

2. Requiring transparency and holistic stakeholder engagement (bringing more of the right people to the table, and encouraging an increased diversity of voices), and

3. Raising questions about the gaps in the draft regulations regarding legal and financial obligations.

Amplifying Pacific Indigenous Leaders voices

Between the July and November meetings, countries met “intersessionally,” or, between sessions, at the Kingston Jamaican Conference Center to discuss ways forward on a number of topics not given time for discussion during the official meetings. TOF has participated in a number of meetings to support conversation on Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) and how to best represent it in the draft regulations.

During this intersessional period, a group of Pacific Indigenous Leaders worked to develop a statement to describe and honor their relationship with the ocean and the deep sea as requiring protection from deep seabed mining. Their statement was delivered on behalf of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and residents of Pacific Small Island Developing States to propose language to guide the definition of “intangible cultural heritage” within the draft regulations. The proposal is guided by international law, Indigenous experience, and principles drawn from the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Principle 3 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development as well as the BBNJ Agreement (otherwise known as the High Seas Treaty).

In November, the facilitator of these intersessional meetings was invited to give a progress report and invite countries to respond to the work of the group, including the proposal by the Pacific Indigenous Leaders. Twelve countries indicated interest in further conversation, including a number of delegations who had not previously engaged on the topic. We hope to see conversation on this proposal and efforts to define “intangible cultural heritage” continue, with those in the room who have expertise on the topic based on lived experiences and traditional knowledge, in particular, Indigenous people and local communities.

Silence Should Not Mean Approval

The ISA Council adopted a decision to help guide the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) of the Authority in its work in the coming year. There was hope the decision would include binding language surrounding the use of the silence procedure (allowing decisions to be automatically agreed if there are no voiced disagreements).

Context: The Silence Procedure

The silence procedure is a method of decision making where those involved in a decision have a specific amount of time (usually a few days) to raise any disagreements, before the decision is finalized. It has been used in the past as an informal manner of reaching consensus, and was only formalized in international bodies like the United Nations General Assembly during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is believed that the highly controversial approval of a contractor’s request to begin test mining in Fall 2022 was a result of the silence procedure.

That was not the case. Instead, the document requests more information for when the silence procedure is used and offers a reminder to the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) that the procedure should be used as a means of decision-making at the end of a consultation process, and not as a substitute for the consultation process. With the loophole from the 2 year rule still open, the LTC’s use of the silence procedure may cause a submitted DSM application to be approved, even if LTC members would have disapproved it given the opportunity for discussion, a concerning possibility.

Fundamental problems: Financial gaps and regulatory concerns

The regulations as currently drafted are not sufficiently protective of anyone – not contractors, not Sponsoring States (countries allowing mining activities), not other Member States, not the ISA itself nor civil society or humankind, and not the marine environment. Rather, they are rife with conflicts of interest, lower than baseline standards, and limited transparency.

The Ocean Foundation has regularly submitted comments and suggestions to highlight the gaps in the regulatory framework. These comments follow standard practice, as seen by a few examples below.

Into 2024 and Beyond

Developing and agreeing to rules of procedure is not glamorous work and it can take days in an international setting. However, without a common understanding of the ways of working, not everyone in the room can be comfortable with the outcomes of a process.

In previous meetings, the facilitators have encouraged countries to make remarks about each regulation and to discuss each area of redlined (newly proposed, not agreed) text. The November 2023 meetings have approached the text differently, with facilitators requesting general comments on large sections of regulations (often 3-10 regulations), causing delegations to deliver 10-15+ minute interventions, as they had prepared to continue working on a more detailed level. Most remarkably, these working method decisions seem to have largely been determined without Council agreement — a few countries noted their concerns with this working method on one of the first days, remarking that there was no decision taken or explanation for this shift in methodology.

The ways of working for the 2024 meetings are still largely unconfirmed. The President of the Council proposed a set of suggestions for working methods, including a consolidated text (the regulations are currently separated out into groups) and encouraged meetings that are more informal than the current structure of the meetings. The use of a consolidated text may further reduce the time spent on individual regulations, limiting the possibility for countries to raise concerns, a necessary working phase that should not be rushed. While Observers and other non-voting members are able to participate in the current structure of the meetings, an increase in more informal meetings may cause important conversations to move behind closed doors, where Observers are not invited to participate. No formal decision was taken on a way forward.

It has become increasingly clear in each working group that there is still much to do, and that consensus is still far away. The Ocean Foundation strongly believes that the responsible way forward to protect the ocean and marine environment is to set a precautionary pause or moratorium on deep seabed mining unless and until scientific research demonstrates mining can be done without harm to the environment.