From plastic bags to newly discovered sea creatures, the ocean’s seabed floor is packed with life, beauty, and traces of human existence.

Human stories, traditions, and beliefs are among these traces , in addition to the physical shipwrecks, human remains, and archeological artifacts that lie on the seafloor. Throughout history, humans have traveled across the ocean as seafaring people, creating new paths to distant lands and leaving behind shipwrecks from weather, wars, and the transatlantic era of African enslavement. Cultures around the world have developed close relationships with marine life, plants, and the spirit of the ocean.

In 2001, global communities came together to more formally recognize and develop a definition and protections for this collective human history. Those discussions, along with over 50 years of multilateral work, resulted in the acknowledgment and establishment of the umbrella term “Underwater Cultural Heritage,” often shortened to UCH.

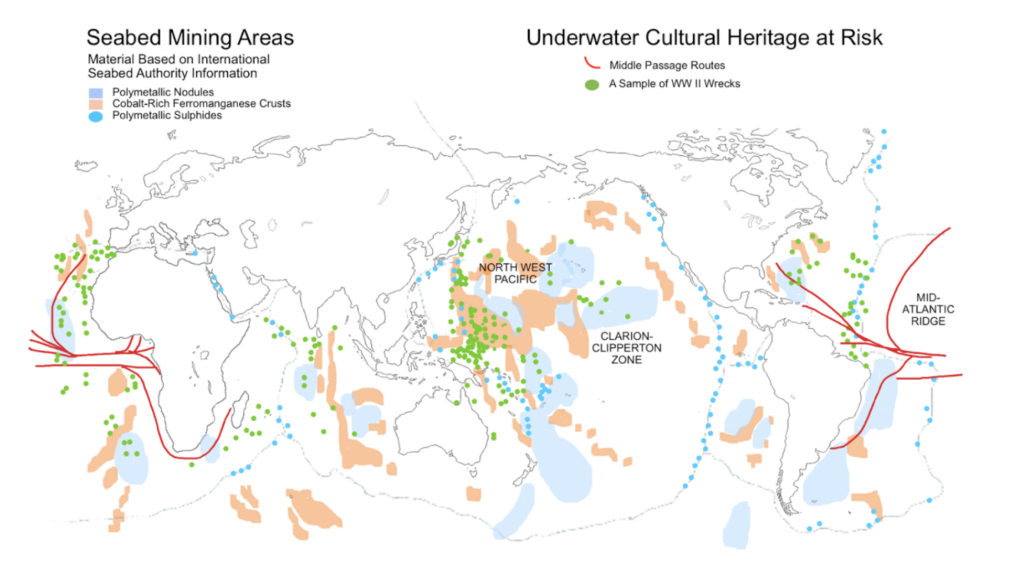

Conversations about UCH are growing thanks to the UN Decade for Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. UCH issues have gained recognition due to the 2022 UN Ocean Conference and an uptick in activity around the potential mining of the seabed in international waters – also known as Deep Seabed Mining (DSM). And, UCH was discussed throughout the 2023 March International Seabed Authority meetings as countries debated the future of DSM regulations.

With 80% of the seabed unmapped, DSM poses a wide array of threats to the known, anticipated, and unknown UCH in the ocean. The unknown extent of damage to the marine environment by commercial DSM machinery also threatens UCH located in international waters. As a result, the protection of UCH has emerged as a topic of concern from Pacific Island Indigenous people – who have extensive ancestral histories and cultural connections to the deep sea and the coral polyps that reside there – in addition to American and African descendants of the Transatlantic Era of African Enslavement, among many others.

What’s Deep Seabed Mining (DSM)? What’s the two-year rule?

Check out our introduction blog and research page for more information!

UCH is currently protected under the 2001 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.

As defined in the Convention, Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) spans all traces of human existence of cultural, historical, or archaeological nature that has been partially or totally immersed, periodically or permanently, under the ocean, in lakes, or in rivers for at least 100 years.

To date, 71 countries have ratified the convention, agreeing to:

- prevent the commercial exploitation and dispersion of Underwater Cultural Heritage;

- guarantee that this heritage will be preserved for the future and situated in its original, found location;

- assist the tourism industry involved;

- enable capacity building and knowledge exchange; and

- enable effective international cooperation as seen in the UNESCO Convention text.

The UN Decade of Ocean Science, 2021-2030, began with the endorsement of the Cultural Heritage Framework Programme (CHFP), a UN Decade Action aiming to integrate historical and cultural connection with the ocean into science and policy. One of CHFP’s first hosted projects for the Decade investigates the UCH of Stone Tidal Weirs, a type of fish trapping mechanism based on traditional ecological knowledge found in Micronesia, Japan, France, and China.

These tidal weirs are just one example of UCH and the global efforts to acknowledge our underwater history. As members of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) work to determine how to protect UCH, the first step is to understand what falls into the broad category of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

UCH exists around the world and across the ocean.

*note: the one global ocean is connected and fluid, and each of the following ocean basins are based on human perception of locations. Overlap between named “ocean” basins is to be expected.

Atlantic Ocean

Spanish Manila Galleons

Between 1565-1815, the Spanish Empire took 400 known voyages in Spanish Manila Galleons across the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins in support of their Asia-Pacific trading efforts and with their Atlantic colonies. These voyages resulted in 59 known shipwrecks, with only a handful excavated.

Transatlantic Era of African Enslavement and the Middle Passage

12.5 million+ enslaved Africans were transported on 40,000+ voyages from 1519-1865 as a devastating part of the transatlantic era of African enslavement and the Middle Passage. An estimated 1.8 million people did not survive the journey and the Atlantic seabed has become their final resting place.

World War I and World War II

The history of WWI and WWII can be found in the shipwrecks, plane wrecks, and human remains found in both the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins. The Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) estimates that, in the Pacific Ocean alone, there are 1,100 wrecks from WWI and 7,800 wrecks from WWII.

Pacific Ocean

Seafaring Travelers

Ancient Austronesian seafarers traveled hundreds of kilometers to explore the southern Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean basins, establishing communities across the region from Madagascar to Easter Island over thousands of years. They relied on wayfinding to develop inter- and intra-island connections and passed down these navigational routes throughout generations. This connection to the sea and coastlines led to Austronesian communities seeing the ocean as a sacred and spiritual place. Today, Austronesian-speaking people are found across the Indo-Pacific region, in Pacific Island countries and islands including Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, the Philippeans, Taiwan, Polynesia, Micronesia, and more – all who share this linguistic and ancestral history.

Ocean Traditions

Communities in the Pacific have embraced the ocean as a part of life, incorporating it and its creatures into many traditions. Shark and whale calling is popular in the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. The Sama-Bajau Sea Nomads are a widely dispersed ethnolinguistic group indigenous to South East Asia who have historically lived at sea on boats tied together into flotillas. The community has lived at sea for over 1,000 years and developed exceptional free-diving skills. Their life at sea has helped them establish a close connection to the ocean and its coastal resources.

Human Remains from the World Wars

In addition to WWI and WWII shipwrecks in the Atlantic, historians have discovered war materials and over 300,000 human remains from WWII alone that currently reside on the Pacific seabed.

Hawai’ian Ancestral Heritage

Many Pacific Islanders, including Indigenous Hawai’ian people, hold a direct spiritual and ancestral connection to the ocean and the deep ocean. This connection is recognized in the Kumulipo, the Hawai’ian creation chant that follows the ancestral lineage of the Hawai’ian royal line to the first believed life in the islands, the deep ocean coral polyp.

Indian Ocean

European Pacific Trading Routes

From the late sixteenth century, many European nations, led by the Portuguese and Dutch, developed East India Trading Companies and conducted trade throughout the Pacific region. These vessels were sometimes lost at sea. Evidence from these voyages litter the seafloor in the Atlantic, Southern, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.

Southern Ocean

Antarctic Exploration

Shipwrecks, human remains, and other marks of human history are an intrinsic part of the exploration of Antarctic waters. Within the British Antarctic Territory alone, 9+ shipwrecks and other UCH sites of interest have been located from the efforts of exploration. In addition, the Antarctic Treaty System acknowledges the wreck of San Telmo, a Spanish shipwreck from the early 1800s with no survivors, as a historic site.

Arctic Ocean

Paths through Arctic Ice

Similar to the UCH found and anticipated in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters, human history in the Arctic Ocean has been tied to determining routes for access to other countries. Many ships froze and sank, leaving no survivors while attempting to travel the Northeast and Northwest passages between the 1800s-1900s. More than 150 whaling ships were lost in this time period.

These examples show just a fraction of the heritage, history, and culture that reflects the human-ocean connection, with the majority of these examples constrained to research completed with a Western lens and perspective. Within conversations around UCH, incorporating a diversity of research, background, and methods to include both traditional and Western knowledge is crucial to ensuring equitable access and protection for all. Much of this UCH is located in international waters and at risk from DSM, especially if DSM proceeds without acknowledging UCH and the steps to protect it. Delegates at the international stage are currently discussing how to do so, but the path forward remains unclear.

The Ocean Foundation believes that regulatory developments surrounding DSM must not be rushed, especially without consultation or engagement with all stakeholders. The ISA also needs to actively engage with prior informed stakeholders, particularly Pacific Indigenous people, to understand and protect their heritage as part of the common heritage of humankind. We support a moratorium unless and until regulations are at least as protective as national law.

A DSM moratorium has been gaining traction and speed over the last few years, with 14 countries agreeing on some form of pause or ban on the practice. Engagement with stakeholders and the incorporation of traditional knowledge, specifically from Indigenous groups with known ancestral connections to the seabed, should be included in all conversations around UCH. We need proper acknowledgment of UCH and its connections to communities all around the world, so that we can protect the common heritage of humankind, physical artifacts, cultural connections, and our collective relationship with the ocean.