By Mark J. Spalding, President, The Ocean Foundation

A version of this blog originally appeared on National Geographic’s Ocean Views

The other week was bookended by talking about ocean acidification. I was in Minneapolis for the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, and a few days later, I was at the Foreign Service Institute of the US Department of State.

As I wrote in a previous blog, the bad news is that ocean acidification is deadly serious. To repeat from that blog:

- Ocean Acidification is real

- It is caused by carbon dioxide emissions from our cars, factories, and power plants

- It is happening fast

- Impact is certain

- Extinctions are certain

- It is already visible in the ecosystem

- Change will happen

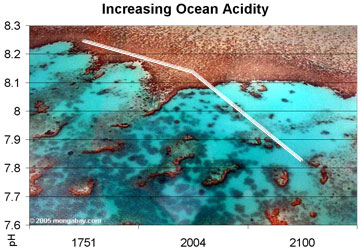

Observed and projected decline in global ocean pH, 1750-2100. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

Since the industrial revolution began, we have released 2 trillion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, and about one-third of it went into the ocean. We initially thought that the ocean taking up CO2 was a good thing – because it took it out of the atmosphere. Unfortunately, we were wrong. There has been a 30% increase in the acidity of the ocean since 1700, and we now expect that by 2100, it will have become a 100% increase. This constitutes a rate of change in ocean chemistry that is 10 times anything scientists can document over the last 50 million years.

The plants and the animals of the ocean evolved to thrive in a fairly neutral pH ocean. Thus, when the chemistry shifts and the ocean becomes more acidic, the plants and animals are immediately affected. The most immediate effects are on calcifiers, those animals who depend on taking up calcium carbonate from ocean waters to build their shells or external skeletons—an ability that is lost when hydrogen bicarbonate is formed instead. From the tiniest pteropods to corals, lobsters, crabs, and shellfish, the very basis of the web of life within our ocean is affected.

Taylor Shellfish Oyster Farm (Photo by Kent Wang)

The food web impacts will affect the seafood industry: both the calcifiers we harvest (lobster, shrimp, scallops, crab, and oysters) and the pollock, salmon, and tuna. In fact, all of the commercial fish species who feed on phytoplanktonic calcifiers.

The good news is that there are steps we can take to meet the challenge of changing ocean chemistry, even as we strive to reduce the root cause—greenhouse gas emissions. We can do something to address this global acidification problem locally. And, we can work to understand ocean acidification (OA) globally, and share with others how to address it locally.

In the upper Northwest of the US, the shellfish industry is worth hundreds of millions of dollars and it depends on clean nearshore waters. A few years ago, shellfish growers in the upper Northwest noticed that their shellfish, especially oysters, were having trouble developing strong, well-formed shells. The culprit was determined to be spikes in the local waters’ acidity, underpinned by a general increase in acidity overall —in other words, changes in the chemistry of coastal waters that made a hostile environment for shellfish. Growers were able to come up with some strategies to mitigate the problem in the short term, but it was clear, especially to industry leaders such as Bill Dewey of Taylor Shellfish, that something bigger needed to be done to preserve the productivity of the coastal waters of the region.

Obviously, reducing carbon emissions now would help reduce acidification in the longer term, but what other solutions existed? Washington State Governor Christine Gregoire convened a Blue Ribbon Commission to review the problem, the known science and solutions, and determine what could be done at the state and local level. The final Commission report made a number of recommendations to address the OA problem. And, to the credit of business, conservation, legislative, and executive leadership, that report did not go sit on a shelf to collect dust as so many reports do.

Instead, the Washington state legislature passed an OA measure that established monitoring protocols, defined strategies that could work to mitigate the problem locally, and created a funding mechanism to help pay for it.

The National Caucus of Environmental Legislators has been working with legislators in other states whose seafood industry is also at risk from changing ocean chemistry.

The National Caucus of Environmental Legislators is an unaffiliated; non-partisan stand alone organization that serves as a forum for information sharing and strategy development on environmental and energy issues. Since 1996, NCEL has grown to nearly 900 state legislators from all 50 states, representing nearly 15% of all state legislators.

On August 16th the NCEL held a meeting in Minneapolis where The Ocean Foundation had the good fortune to be on a panel about how state legislatures could meet the challenge of ocean acidification head on. More than 500 legislators attended the meeting. It was exciting and inspiring to meet so many people working so hard on the environmental, economic, and social health of their constituents and their state.

Now we can roll our sleeves up and help coastal states do what they can. The good news is that most of the strategies for addressing OA have multiple benefits. Building resilience means replanting the seagrass, mangroves, and marshes that take up carbon and filter the water. Restoring habitat doesn’t just help the shellfish industry—it reestablishes critical nursery and feeding areas for an array of species, many of whom represent a critical protein source for human and animal communities. Ensuring that additional pollutants such as nitrogen do not further stress already vulnerable areas helps improve water quality for human communities as well.

StrategicPlanAt the Foreign Service Institute in Northern Virginia on August 21st, the State Department gathered a roomful of representatives from the Inter-Agency Working Group on OA. The government entities represented included NOAA, NASA, the US Navy, US Fish & Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, US Geological Survey, the State Department, the Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Some of the top OA experts in the room talked about the chemistry changes from pH impairment, and the biological effects of those changes. They also discussed the actions that the federal government is taking as well as the actions that are happening in the for-profit and nonprofit sectors. We also talked about the global need for monitoring and mitigation—after all, one in seven people depends on the ocean for protein—OA has the potential to undermine food security for some of the most vulnerable coastal communities and island nations.

This allowed for a refreshing and robust dialogue that involved foreign service desk officers representing numerous regions around the world, and foreign service officers at the State Department. The conversation centered on how embassies could be engaged in sharing knowledge about OA as well as about how to respond to it. In addition to the soft power of diplomacy, how international assistance agencies could assist in financially and with in-kind technology to address this significant problem was discussed.

Together we can work to address causes through mitigation and remediation. We can address consequences by taking ameliorative and adaptative actions, and we can learn where and when through monitoring and observation. Let us support the states that are taking legislative action, and let’s do more to get funding for international monitoring and observation type research to help other nations to avert the potential harm of ocean acidification to food security, ocean health, and the web of life.