By Ben Scheelk, Program Associate

Volunteering in Costa Rica Part III

There is just something about playing with mud, which makes you feel primal. Rubbing big globs of greasy, coarse-grained earth batter in your hands, letting it ooze through your fingers as you squeeze it into an amorphous ball—just the thought of such a messy act seems verboten. Perhaps we can attribute some of that to childhood conditioning: scolding parents, always ruining new school clothes on the first day, and the nightly chore of having to scrub under dirt-encrusted fingernails until red and raw before eating dinner. Perhaps our guilty pleasure traces back to memories of bombarding siblings and the other neighborhood children with mud grenades. Maybe it was just indulging in too many mud pies.

For whatever reason it may feel forbidden, playing with mud certainly is liberating. It is a curious substance that, when generously applied, allows for personal rebellion against soap-addicted social conventions and white tablecloth norms—not to mention accidental itch-induced facial applications.

There was certainly a lot of mud to play with when our SEE Turtles group headed to LAST’s mangrove restoration project to volunteer with planting for a day.

The previous day’s dream-like experience of capturing, measuring, and tagging sea turtles was replaced with what felt like real hard work. It was hot, sticky, buggy (and did I mention muddy?). To add to the whole sordid affair, a very friendly little pooch smothered kisses on everyone as we sat in the dirt packing bags, our crusty brown hands unable to discourage his enthusiastic and adorable advances. But it felt good. Getting really dirty. Now this was volunteering. And we loved it.

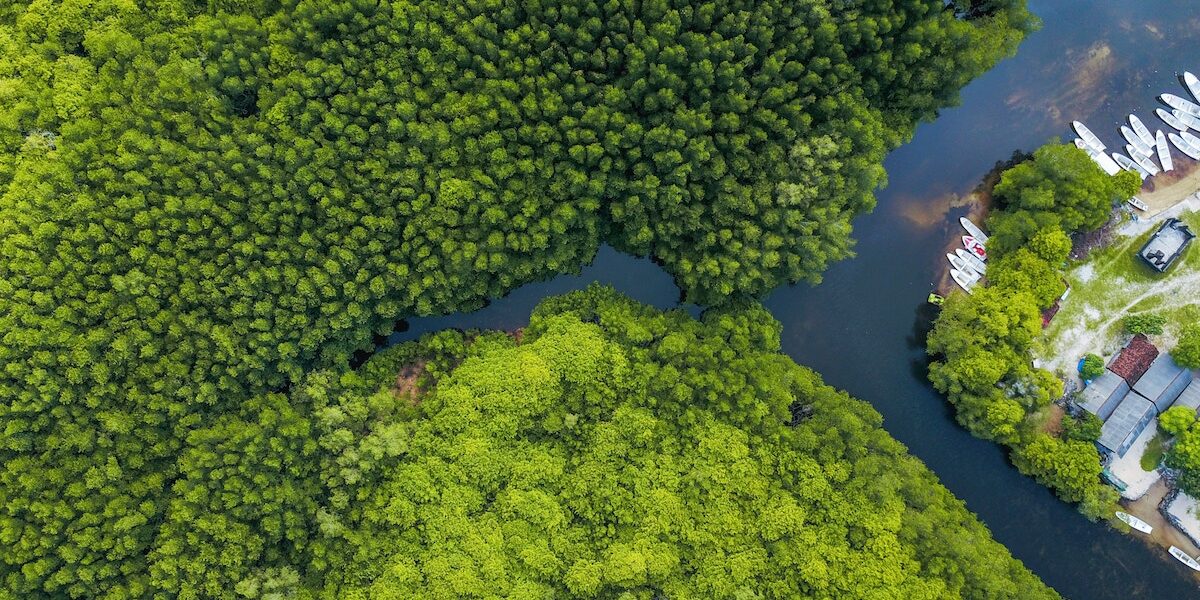

Enough can’t be said about the importance of mangrove forests to maintaining a healthy, functioning coastal ecosystem. Not only do they serve as critical habitat for a wide variety of animals, but they also play a significant role in nutrient cycling, and act as nurseries for young fauna like fish, birds, and crustaceans. Mangroves are also the best form of shoreline protection. Their tangled roots and buttress trunks minimize erosion from waves and water movement, in addition to trapping sediments, which reduces the turbidity of coastal waters and maintains a stable shoreline.

Sea turtles, to the surprise of many biologists who once assumed they relied solely on coral reefs for feeding, have been found to spend a significant amount of time around mangroves foraging. Researchers from the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative, a project of The Ocean Foundation, have shown how hawksbill turtles sometimes nest in sandy patches of beach that exist in between mangroves, which underlines the importance of these ecosystems to preserving this iconic and endangered species.

Yet, despite the many benefits mangrove wetlands provide, they are too-often the victims of coastal development. Bordering nearly three quarters of the margins of tropical coastlines around the world, mangrove forests have been destroyed at an alarming rate to make room for tourist resorts, shrimp farms, and industry. But humans are not the only threat. Natural disasters can also devastate mangrove forests, as was the case in Honduras when Hurricane Mitch wiped out 95% of all mangroves on Guanaja Island in 1998. Similar to the work we did with LAST in Gulfo Dulce, The Ocean Foundation’s fiscally sponsored project, Guanaja Mangrove Restoration Project, has replanted over 200,000 red mangroves propagules, with plans to plant the same number of white and black mangroves in the coming years to ensure forest diversity and resiliency.

Beyond the pivotal role mangrove wetlands serve in coastal ecosystems, they also have a part to play in combatting climate change. In addition to fortifying shorelines and minimizing the impacts of dangerous storm surges, the ability of mangrove forests to sequester large amounts of carbon dioxide has made them a very desirable carbon offset in the emerging “blue carbon” market. Researchers, including from The Ocean Foundation’s project, Blue Climate Solutions, are actively working with policymakers to design new strategies for implementing blue carbon offsets as part of an integrated plan to stabilize and eventually reduce the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change.

While all of these are compelling reasons to preserve and restore mangrove wetlands, I must admit that what drew me most to this activity was not my noble intentions to save nature’s finest coastal ecosystem engineer, but rather I just really enjoyed playing in the mud.

I know, it’s childish, but nothing quite compares to the incredible feeling you get when you have the opportunity to go out in the field and connect in a real and visceral way with the work that has been, up until that time, something which lived only in your computer screen in 2-D.

The third dimension makes all the difference.

It’s the part that brings clarity. Inspiration. It leads to greater understanding of your organization’s mission—and what needs to be done to achieve it.

Spending the morning in the dirt packing bags with mud and planting mangrove seeds gave me that feeling. It was dirty. It was fun. It was even a little bit primeval. But, above all, it just felt real. And, if planting mangroves is a part of a winning global strategy to save our coasts and the planet, well, that’s just icing on the mud-cake.