This project is funded by Shark Conservation Fund and National Geographic Society.

The smalltooth sawfish is one of the most enigmatic creatures on Earth. Yes, it’s a fish, in that all sharks and rays are considered fish. It is not a shark but a ray. Only, it has a very unique attribute that sets it apart even from rays. It has a “saw” – or in scientific terms, a “rostrum” – covered in teeth on both sides and extending from the front of its body.

This saw has given it a distinct edge. The smalltooth sawfish will swim through the water column using violent thrusts that allow it to stun prey. It will then swing around to pick up its prey with its mouth — which, like a ray, is on the bottom of its body. In fact, there are three families of sharks and rays that use saws as hunting appendages. This clever and effective foraging tool has evolved three different times.

The sawfish’s rostra has also been a curse.

It is not only a curio relished for millennia by different cultures much like ivory or shark fins. Nets also easily ensnare them. As uncommon as the sawfish is, it is not suitable as a food source. It is highly cartilaginous, making extraction of meat a very messy affair. Never quite abundant but now rare throughout its range in the Caribbean, the smalltooth sawfish is hard to find. While there are hope spots (parts of the ocean that need protection because of its wildlife and significant underwater habitats) in Florida Bay and most recently in the Bahamas, it is extremely hard to find in the Atlantic.

As part of a project called Initiative to Save Caribbean Sawfish (ISCS), The Ocean Foundation, Shark Advocates International, and Havenworth Coastal Conservation are bringing decades of work in the Caribbean to help find this species. Cuba is a prime candidate to find one, due to its massive size and anecdotal evidence from fishers along its 600 miles of northern coastline.

Cuban scientists Fabián Pina and Tamara Figueredo conducted a study in 2011, where they spoke with over one hundred fishers. They found conclusive evidence that sawfish were in Cuba from catch data and visual sightings. ISCS partner, Dr. Dean Grubbs of Florida State University, had tagged several sawfish in Florida and the Bahamas and independently suspected that Cuba could be another hope spot. The Bahamas and Cuba are separated only by a deep channel of water — in some places only 50 miles wide. Only adults have been found in Cuban waters. So, the common hypothesis is that any sawfish found in Cuba have migrated from Florida or Bahamas.

Trying to tag a sawfish is a shot in the dark.

Especially in a country where none have been documented scientifically. TOF and Cuban partners believed more information was needed before a site could be identified to attempt a tagging expedition. In 2019, Fabián and Tamara chatted with fishers going as far east as Baracoa, the far eastern hamlet where Christopher Columbus first landed in Cuba in 1494. These discussions not only revealed five rostra collected by fishers over the years, but helped pinpoint where tagging could be attempted. The isolated key of Cayo Confites in north central Cuba was selected based on these discussions and the vast, undeveloped expanses of seagrass, mangrove, and sand flats – which sawfish love. In the words of Dr. Grubbs, this is considered “sawfishy habitat”.

In January, Fabián and Tamara spent days laying long lines from a rustic, wooden fishing boat.

After five days of catching nearly nothing, they headed back to Havana with their heads down. On the long drive home, they received a call from a fisher in Playa Girón in southern Cuba, who pointed them to a fisher in Cardenas. Cardenas is a small Cuban city on Cardenas Bay. Like many bays on the north coast, it would be considered very sawfishy.

Upon arriving in Cardenas, the fisherman took them into his home and showed them something that rattled all of their preconceptions. In his hand the fisher held a small rostrum, considerably smaller than anything they had seen. By the looks of it, he was holding a juvenile. Another fisher found it in 2019 while emptying his net in Cardenas Bay. Sadly, the sawfish was dead. But this find would provide preliminary hope that Cuba might host a resident population of sawfish. The fact that the find was so recent was equally promising.

Genetic analysis of tissue of this juvenile, and the other five rostra, will help piece together whether Cuba’s sawfish are simply opportunistic visitors or part of a homegrown population. If the latter, there is hope of implementing fisheries policies to protect this species and go after illegal poachers. This takes on additional relevance as Cuba does not see sawfish as a fishery resource.

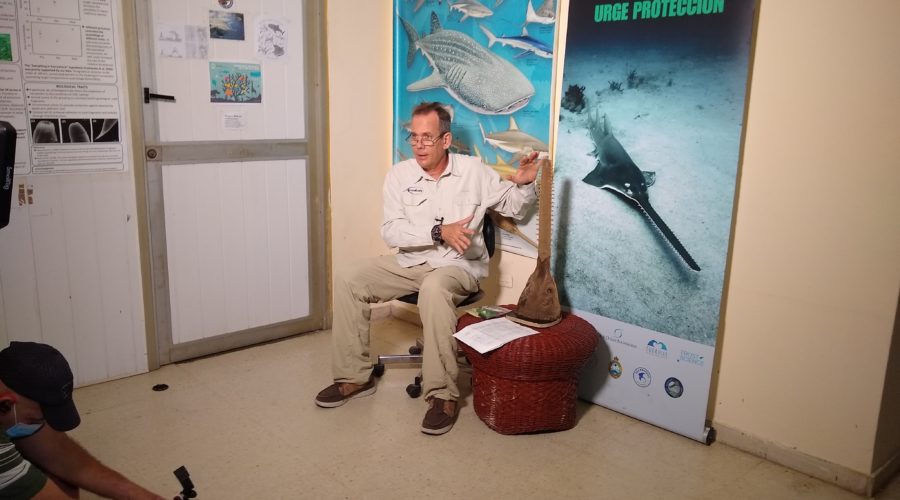

Left Photo: Dr. Pina handing a certificate of appreciation to Cardenas fisherman Osmany Toral Gonzalez

Right Photo: Dr. Fabian Pina unveiling the Cardenas specimen at the Center for Marine Research, University of Havana

The story of the Cardenas sawfish is an example of what makes us love science.

It is a slow game, but what seems like small discoveries can change the way we think. In this case, we are celebrating the death of a young ray. But, this ray may provide hope for its peers. Science can be a painstakingly slow process. However, the discussions with fishers are answering questions. When Fabián called me with the news he told me, “hay que caminar y coger carretera”. In English, this means you have to walk slowly on the fast highway. In other words patience, perseverance and unrelenting curiosity will pave the way to the big find.

This find is preliminary, and in the end it could still mean Cuba’s sawfish are a migratory population. However, it provides hope that Cuba’s sawfish could be on better footing than we ever believed.