Coral reefs can handle a lot of chronic and acute harms, until they can’t. Once a reef tract crosses the threshold from a coral-dominated system to a micro-algae dominated system in the same place; it is very hard to come back.

“Bleaching will kill coral reefs; ocean acidification will keep them dead.”

– Charlie Veron

I was honored last week to be invited by the Central Caribbean Marine Institute and its patron, HRH The Earl of Wessex, to attend the Rethinking the Future for Coral Reefs Symposium, at St. James Palace in London.

This was not your normal windowless conference room in another nameless hotel. And this symposium was not your normal get together. It was multi-disciplinary, small (only about 25 of us in the room), and to top it off Prince Edward sat with us for the two days of discussion about coral reef systems. This year’s mass bleaching event is the continuation of an event that began in 2014, as the result of warming sea water. We expect such global bleaching events to increase in frequency, which means we have no choice but to rethink the future of coral reefs. Absolute mortality in some areas and for some species is inevitable. It is a sad day when we have to adjust our thinking to “things are going to get worse, and sooner than we thought.” But, we are on it: Figuring out what all of us can do!

A coral reef is not just coral, it is a complex yet delicate system of species living together and depending upon one another. Coral reefs are easily one of the most sensitive ecosystems in all of our planet. As such, they are predicted to be the first system to collapse in the face of warming waters, changing ocean chemistry, and the deoxygenation of the ocean as a result of our greenhouse gas emissions. This collapse was previously predicted to be in full effect by 2050. The consensus of those gathered in London was that we need to change this date, move it up, as this most recent mass bleaching event has resulted in the biggest die off of coral in history.

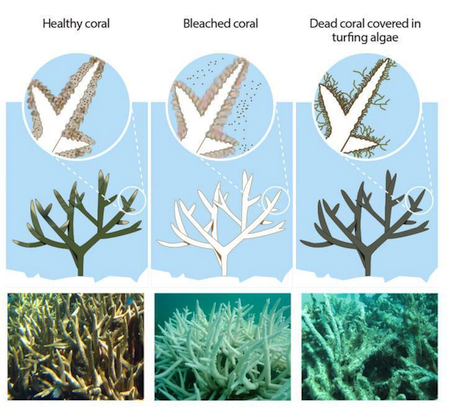

These photos were taken at three different times just 8 months apart near American Samoa.

Coral reef bleaching is a very modern phenomenon. Bleaching occurs when symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) dies due to excess heat, causing photosynthesis to halt, and depriving corals of their food resource. Following the 2016 Paris Agreement, we are hoping to cap the warming of our planet at 2 degrees Celsius. The bleaching we are seeing today is occuring with only 1 degree Celsius of global warming. Only 5 of the last 15 years have been free of bleaching events. In other words, new bleaching events are now coming sooner and more frequently, leaving little time for recovery. This year is so severe that even species we thought of as survivors are victim to bleaching.

This recent heat assault only adds to our losses of coral reefs. Pollution and overfishing are escalating and they must be addressed in order to support what resilience can occur.

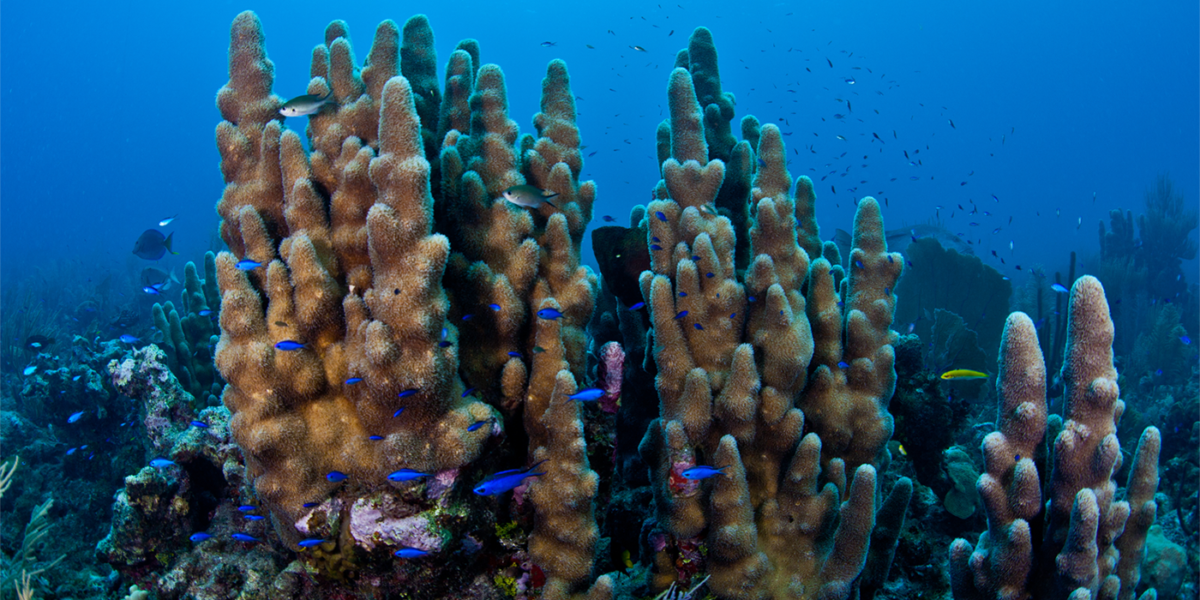

Our experience tells us that we need to take a holistic approach to saving coral reefs. We need to stop stripping them of the fish and inhabitants that have formed a balanced system over millennia. For over 20 years, our Cuba program has studied and worked to conserve the Jardines de la Reina reef. Due to their research, we know that this reef is healthier and more resilient than other reefs in the Caribbean. The trophic levels from top predators to microalgae are still there; as are the seagrasses and mangroves in the adjacent gulf. And, they are all still largely in balance.

Warmer water, excess nutrients and pollution do not respect boundaries. With that in mind, we know we cannot use MPAs to change-proof coral reefs. But we can actively pursue public acceptance and support of “no take” marine protected areas in coral reef ecosystems to maintain balance and increase resilience. We need to prevent anchors, fishing gear, divers, boats, and dynamite from turning coral reef tracts into fragments. At the same time, we must stop putting bad stuff into the ocean: marine debris, excess nutrients, toxic pollution, and dissolved carbon that leads to ocean acidification.

We must also work to restore coral reefs. Some corals can be raised in captivity, in farms and gardens in nearshore waters, and then “planted” on degraded reefs. We can even identify coral species that are more tolerant to change in water temperature and chemistry. One evolutionary biologist recently stated that there will be members of the various coral populations that will survive as a result of the massive changes going on on our planet, and that those left over will be much stronger. We cannot bring back big, old corals. We know that the scale of what we are losing far exceeds the scale we are humanly capable of restoring, but every bit may help.

In combination with all of these other efforts, we must also restore adjacent seagrass meadows and other symbiotic habitats. As you may know, The Ocean Foundation, was originally called the Coral Reef Foundation. We established the Coral Reef Foundation nearly two decades ago as the first coral reef conservation donors’ portal—providing both expert advice about successful coral reef conservation projects and easy mechanisms for giving, especially to small groups in distant places who were carrying much of the burden of place-based coral reef protection. This portal is alive and well and helping us get funding to the right people doing the best work in the water.

To recap: Coral reefs are very vulnerable to the impacts of human activity. They are particularly vulnerable to changes in temperature, chemistry, and sea level. It is a race against the clock to eliminate the harm from pollutants so that those coral that can survive, will survive. If we protect reefs from upstream and local human activities, preserve symbiotic habitats, and restore degraded reefs, we know that some coral reefs can survive.

The conclusions from the meeting in London were not positive—but we all agreed we have to do our best to make positive change where we can. We must use a systems approach to find solutions that avoid the temptation of “silver bullets,” especially those that may have unintended consequences. There must be a portfolio approach of actions to build resilience, drawn from best available practices, and well informed by science, economics and law.

We cannot ignore the collective steps each of us is taking on behalf of the ocean. The scale is huge, and at the same time, your actions matter. So, pick up that piece of trash, avoid single use plastics, clean up after your pet, skip fertilizing your lawn (especially when rain is in the forecast), and check out how to offset your carbon footprint.

We at The Ocean Foundation have a moral obligation to steer the human relationship with the ocean to one that is healthy so that coral reefs can not only survive, but thrive. Join us.