“If everything on land were to die tomorrow, everything in the ocean would be fine. But if everything in the ocean were to die, everything on land would die too.”

ALANNA MITCHELL | AWARD-WINNING CANADIAN SCIENCE JOURNALIST

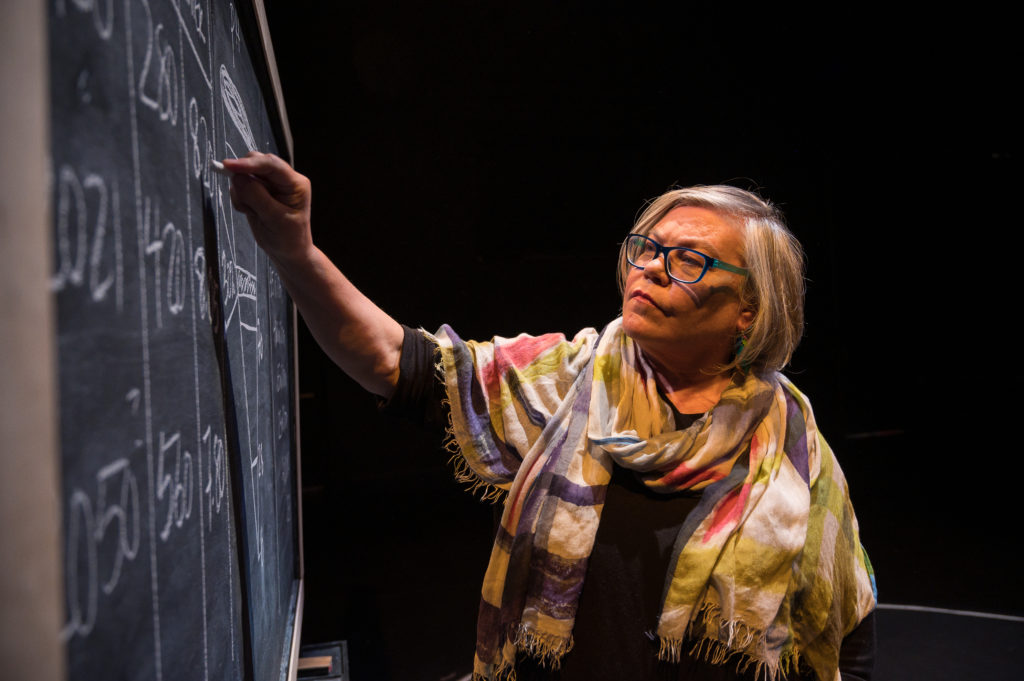

Alanna Mitchell stands on a small black platform, in the center of a chalk-drawn white circle about 14 feet in diameter. Behind her, a chalkboard holds a large sea shell, a piece of chalk, and an eraser. To her left, a glass-topped table houses a pitcher of vinegar and a single glass of water.

I watch in silence with my fellow audience members, perched on a chair in the Kennedy Center’s REACH plaza. Their COAL + ICE exhibit, a documentary photography exhibition showcasing climate change’s deep impact, envelopes the stage and adds a layer of eeriness to the one-woman play. On one projector screen, a fire roars across an open field. Another screen showcases the slow and sure destruction of ice caps in Antarctica. And in the center of it all, Alanna Mitchell stands and tells the story of how she discovered that the ocean contains the switch for all life on earth.

“I’m not an actor,” Mitchell confesses to me just six hours before, in between sound checks. We’re standing in front of one of the exhibit screens. Hurricane Irma’s grasp on Saint Martin in 2017 streams on a loop behind us, with palm trees shaking in the wind and cars capsizing under a surging flood. It’s a stark contrast to Mitchell’s calm and optimistic demeanor.

In reality, Mitchell’s Sea Sick: The Global Ocean in Crisis was never supposed to be a play. Mitchell began her career as a journalist. Her father was a scientist, chronicling the prairies in Canada and teaching the studies of Darwin. Naturally, Mitchell became fascinated with how the systems of our planet work.

“I started writing about the land and the atmosphere, but I had forgotten about the ocean.” Mitchell explains. “I just didn’t know enough to realize that the ocean is the critical piece of that whole system. So when I discovered it, I just launched on this whole journey of years of inquiry with scientists about what’s happened to the ocean.”

This discovery led Mitchell to write her book Sea Sick in 2010, about the altered chemistry of the ocean. While on tour discussing her research and passion behind the book, she ran into Artistic Director Franco Boni. “And he said, you know, ‘I think we can turn that into a play.’”.

In 2014, with the help of The Theatre Centre, based in Toronto, and co-directors Franco Boni and Ravi Jain, Sea Sick, the play, was launched. And on March 22, 2022, after years of touring, Sea Sick made its debut in the U.S. at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

As I stand with Mitchell and let her soothing voice wash over me – despite the hurricane on the exhibit screen behind us – I think about the power of the theater to instill hope, even in times of chaos.

“It’s an incredibly intimate art form and I love the conversation it opens up, some of it unspoken, between me and the audience,” Mitchell says. “I believe in the power of art to change hearts and minds, and I think that my play gives people context for understanding. I think it maybe helps people fall in love with the planet.”

In the REACH plaza, Mitchell reminds us that the ocean is our major life support system. When the fundamental chemistry of the ocean changes, that’s a risk for all life on earth. She turns to her chalkboard as Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin’” echoes in the background. She etches a series of numbers in three sections from right to left, and labels them “Time,” “Carbon,” and “pH”. At first glance, the numbers are overwhelming. But as Mitchell turns back around to explain, the reality is even more jarring.

“In just 272 years, we’ve pushed the chemistry of the planet’s life-support systems to places it hasn’t been in for tens of millions of years. Today, we have more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than we’ve had for at least 23 million years… And today, the ocean is more acidic than it’s been for 65 million years.”

“That’s a harrowing fact,” I mention to Mitchell during her sound check, which is precisely how Mitchell wants her audience to react. She recalls reading the first big report on ocean acidification, released by the Royal Society of London in 2005.

“It was very, very groundbreaking. Nobody knew about this,” Mitchell pauses and gives a soft smile. “People were not talking about it. I was going from one research vessel to another, and these are really eminent scientists, and I would say, ‘This is what I just discovered,’ and they would say ‘…Really?’”

As Mitchell puts it, scientists weren’t putting together all facets of ocean research. Instead, they studied small parts of the whole ocean system. They didn’t know yet how to connect these parts to our global atmosphere.

Today, ocean acidification science is a much larger part of international discussions and the framing of the carbon issue. And unlike 15 years ago, scientists are now studying creatures in their natural ecosystems and linking these findings back to what happened hundreds of millions of years ago – to find trends and trigger points from previous mass extinctions.

The downside? “I think we’re increasingly aware of how tiny the window is to really make a difference and allow life as we know it to continue,” Mitchell explains. She mentions in her play, “This is not my father’s science. In my father’s day, scientists were taking a whole career to look at a single animal, figure out how many babies it has, what it eats, how it spends the winter. It was…leisurely.”

So, what can we do?

“Hope is a process. It’s not an end point.”

ALANNA MITCHELL

“I like to quote a climate scientist from Columbia University, her name is Kate Marvel,” Mitchell pauses for a second to remember. “One of the things she said about the most recent round of reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is that it’s really important to hold two ideas in your head at once. One is how much there is to be done. But the other is how far we’ve come, already. And that’s what I‘ve come to. For me, hope is a process. It’s not an end point.”

In the whole history of life on the planet, this is an unusual time. But according to Mitchell, this just means that we’re at a perfect juncture in human evolution, where we have a “marvelous challenge and we get to figure out how to approach it.”

“I want people to know what’s actually at stake and what we’re doing. Because I think people forget about that. But I also think it’s important to know that it’s not game over yet. We still have some time to make things better, if we choose to. And that’s where theater and art come in: I believe that it’s a cultural impulse that will get us to where we need to go.”

As a community foundation, The Ocean Foundation knows first hand the challenges in raising public awareness about issues of overwhelming global scale while offering solutions of hope. The arts play a critical role in translating science to audiences who may be learning about an issue for the first time, and Sea Sick does just that. TOF is proud to serve as a carbon offsetting partner with The Theatre Centre to support coastal habitat conservation and restoration.

For more information about Sea Sick, click here. Learn more about Alanna Mitchell here.

For more information about The Ocean Foundation’s International Ocean Acidification Initiative, click here.