BACK TO RESEARCH

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. U.S. Plastics Policy

– 2.1 Sub-National Policies

– 2.2 National Policies

3. International Policies

– 3.1 Global Treaty

– 3.2 Science Policy Panel

– 3.3 Basel Convention Plastic Waste Amendments

4. Circular Economy

5. Green Chemistry

6. Plastic and Ocean Health

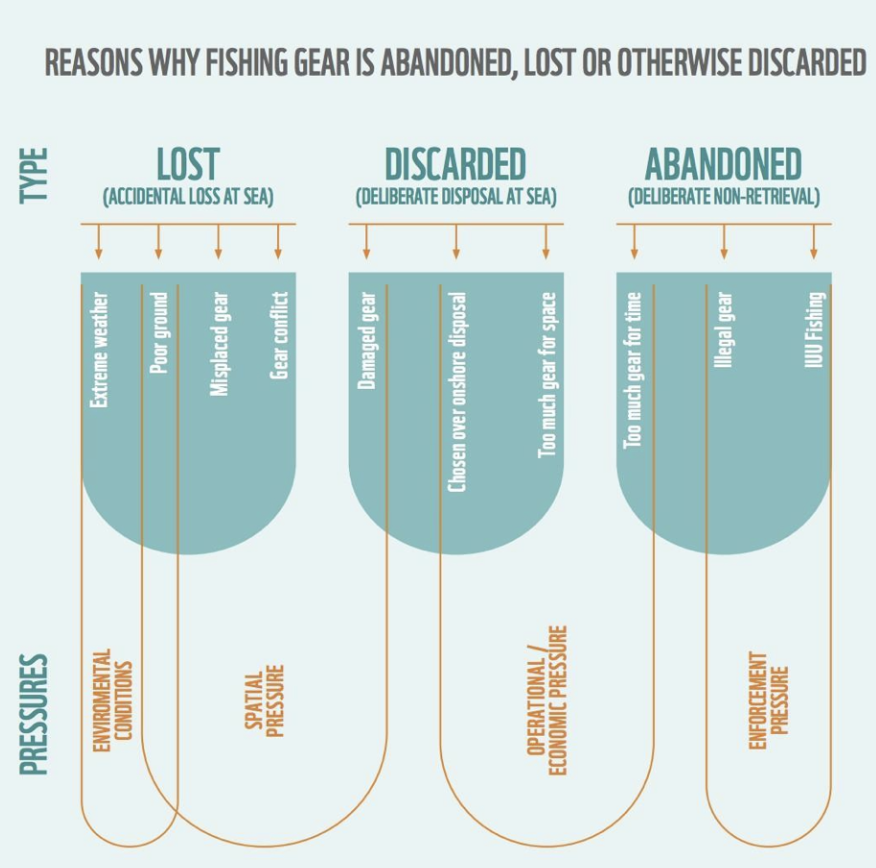

– 6.1 Ghost Gear

– 6.2 Effects on Marine Life

– 6.3 Plastic Pellets (Nurdles)

7. Plastic and Human Health

8. Environmental Justice

9. History of Plastic

10. Miscellaneous Resources

We’re influencing sustainable production and consumption of plastics.

Read about our Plastics Initiative (PI) and how we’re working to achieve a truly circular economy for plastics.

1. Introduction

What is the scope of the plastics problem?

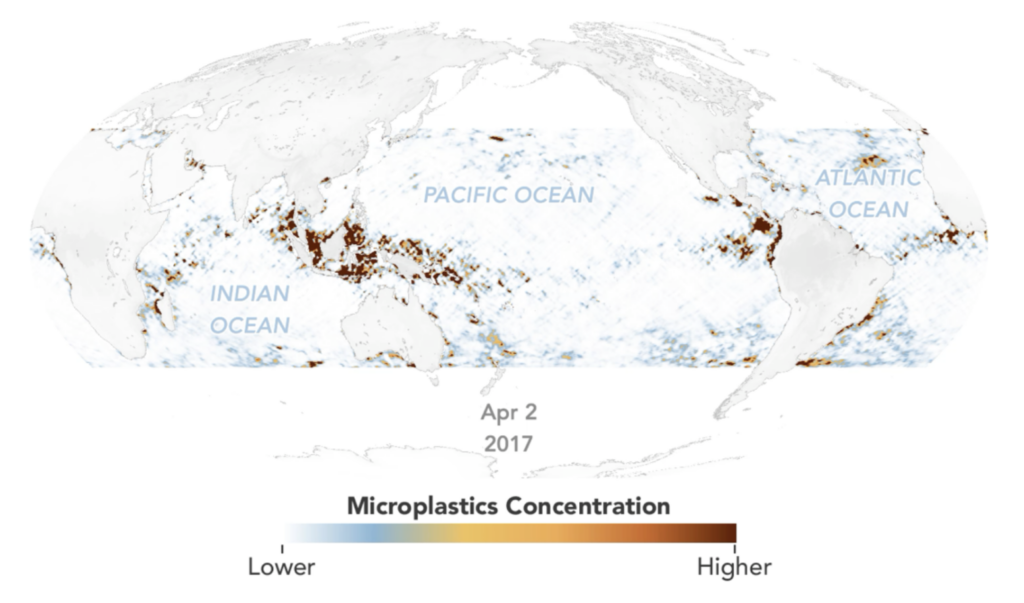

Plastic, the most common form of persistent marine debris, is one of the most pressing issues in marine ecosystems. Although it is difficult to measure, an estimated 8 million metric tons of plastic are added to our ocean annually, including 236,000 tons of microplastics (Jambeck, 2015), which is equal to more than one garbage truck of plastic dumped into our ocean every minute (Pennington, 2016).

It is estimated that there are 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris in the ocean, 229,000 tons floating on the surface, and 4 billion plastic microfibers per square kilometer litter in the deep sea (National Geographic, 2015). The trillions of plastic pieces in our ocean formed five massive garbage patches, including the Great Pacific Garbage patch which is larger than the size of Texas. In 2050, there will be more plastic in the ocean by weight than fish (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016). The plastic isn’t contained to our ocean either, it is in the air and foods we eat to the point where each person is estimated to consume a credit card worth of plastic every week (Wit, Bigaud, 2019).

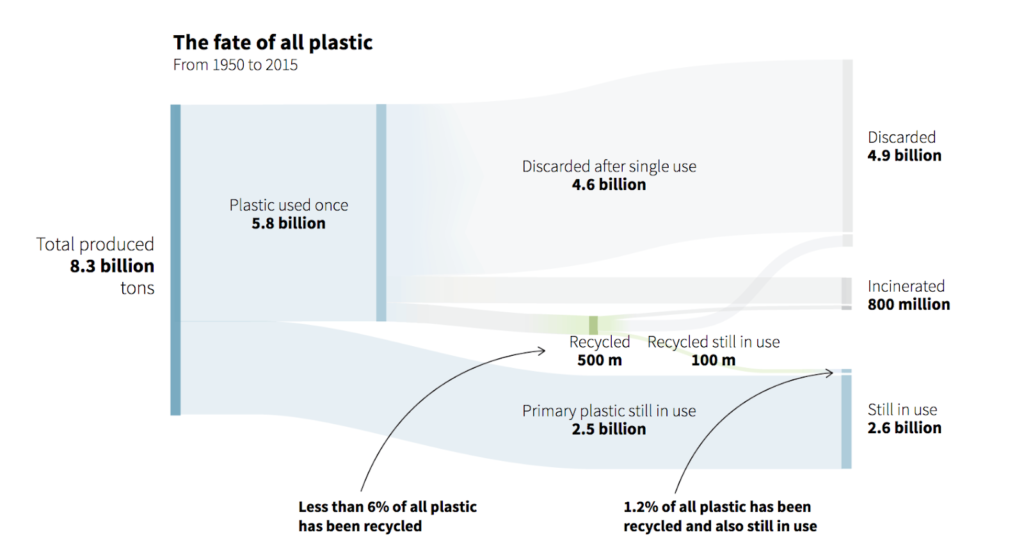

Most of the plastic entering the waste stream ends up improperly disposed of or in landfills. In 2018 alone, there were 35 million tons of plastic produced in the United States, and of that only 8.7 percent of plastic was recycled (EPA, 2021). Plastic use today is virtually unavoidable and it will continue to be a problem until we re-design and transform our relationship to plastics.

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

- Plastics in landfills: Plastic is often lost or blown away during transport to landfills. The plastic then clutters around drains and enters waterways, eventually ending up in the ocean.

- Littering: Litter dropped on the street or in our natural environment is carried by wind and rainwater into our waters.

- Down the drain: Sanitary products, like wet wipes and Q-tips, are often flushed down the drain. When clothes are washed (especially synthetic materials) microfibers and microplastics are released into our wastewater through our washing machine. Finally, cosmetic and cleaning products with microbeads will send microplastics down the drain.

- Fishing Industry: Fishing boats may lose or abandon fishing gear (see Ghost Gear) in the ocean creating deadly traps for marine life.

Why is plastic in the ocean an important problem?

Plastic is responsible for harming marine life, public health, and the economy at a global level. Unlike some other forms of waste, plastic doesn’t completely decompose, so it will remain in the ocean for centuries. Plastic pollution indefinitely leads to environmental threats: wildlife entanglement, ingestion, alien species transport, and habitat damage (see Effects on Marine Life). Additionally, marine debris is an economic eyesore that degrades the beauty of the natural coastal environment (see Environmental Justice).

The ocean not only has immense cultural significance but serves as the primary livelihood for coastal communities. Plastics in our waterways threaten our water quality and marine food sources. Microplastics make their way up the food chain and threaten human health (See Plastic and Human Health).

As ocean plastic pollution continues to grow, these resulting problems are only going to worsen unless we take action. The burden of plastic responsibility should not rest solely on the consumers. Rather, by redesigning plastic production before it even reaches the end-users, we can guide manufacturers towards production-based solutions to this global problem.

Back to top

2. U.S. Plastics Policy

2.1 Sub-National Policies

Schultz, J. (2021, February 8). State Plastic Bag Legislation. National Caucus of Environmental Legislators. http://www.ncsl.org/research/environment-and-natural-resources/plastic-bag-legislation

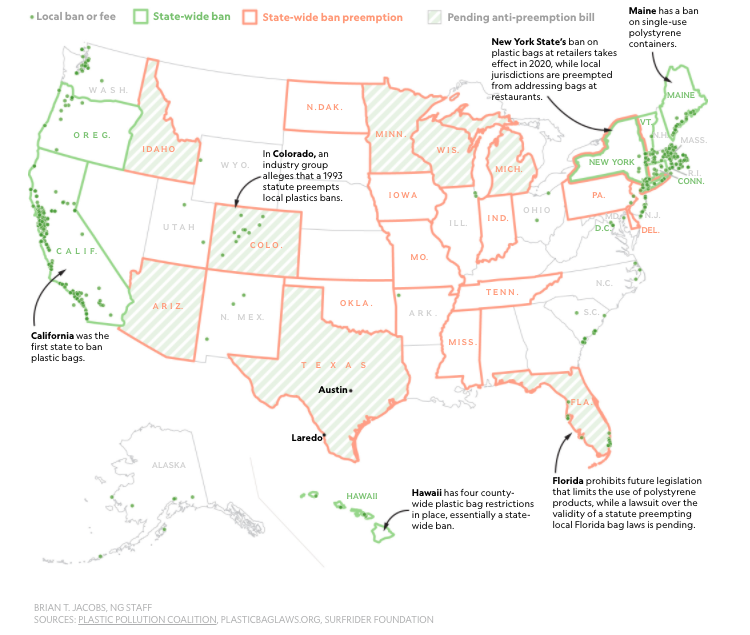

Eight states have legislation reducing the production/consumption of single-use plastic bags. The cities of Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle have also banned plastic bags. Boulder, New York, Portland, Washington D.C., and Montgomery County Md. have banned plastic bags and enacted fees. Banning plastic bags is an important step, as they are one of the most commonly found items in ocean plastics pollution.

Gardiner, B. (2022, February 22). How a dramatic win in plastic waste case may curb ocean pollution. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/how-a-dramatic-win-in-plastic-waste-case-may-curb-ocean-pollution

In December 2019, anti-pollution activist Diane Wilson won a landmark case against Formosa Plastics, one of the world’s largest petrochemical companies, for decades of illegal plastic nurdle pollution along Texas’ Gulf Coast. The $50 million settlement represents a historic victory as the largest award ever granted in a citizen suit against an industrial polluter under the U. S. Clean Water Act. In accordance with the settlement, Formosa Plastics has been ordered to reach “zero-discharge” of plastic waste from its Point Comfort factory, pay penalties until toxic discharges cease, and fund the clean up of plastic that’s accumulated throughout Texas’ affected local wetlands, beaches, and waterways. Wilson, whose tireless work earned her the prestigious 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize, donated the entire settlement to a trust, to be used for a variety of environmental causes. This groundbreaking citizen suit has set off ripples of change across a mammoth industry that too often pollutes with impunity.

Gibbens, S. (2019, August 15). See the complicated landscape of plastic bans in the U.S. National Geographic. nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/08/map-shows-the-complicated-landscape-of-plastic-bans

There are many court battles ongoing in the United States where cities and states disagree over whether it is legal to ban plastic or not. Hundreds of municipalities across the United States have some sort of plastic fee or ban, including some in California and New York. But seventeen states say that it is illegal to ban plastic items, effectively banning the ability to ban. The bans that are in place are working to reduce plastic pollution, but many people say that fees are better than outright bans at changing consumer behavior.

California Ocean Protection Council. (2022, February). Statewide Microplastics Strategy. https://www.opc.ca.gov/webmaster/ftp/pdf/agenda_items/ 20220223/Item_6_Exhibit_A_Statewide_Microplastics_Strategy.pdf

With the adoption of Senate Bill 1263 (Sen. Anthony Portantino) in 2018, California State Legislature recognized the need for a comprehensive plan to address the pervasive and persistent threat of microplastics in the state’s marine environment. The California Ocean Protection Council (OPC) published this Statewide Microplastic Strategy, providing a multi-year roadmap for state agencies and external partners to work together to research and ultimately reduce toxic microplastic pollution across California’s coastal and aquatic ecosystems. Foundational to this strategy is a recognition that the state must take decisive, precautionary action to mitigate microplastic pollution, while scientific understanding of microplastics sources, impacts, and effective reduction measures continue to grow.

HB 1085 – 68th Washington State Legislature, (2023-24 Reg. Sess.): Reducing Plastic Pollution. (2023, April). https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?Year=2023&BillNumber=1085

In April 2023, the Washington State Senate unanimously passed House Bill 1085 (HB 1085) to mitigate plastic pollution in three distinct ways. Sponsored by Rep. Sharlett Mena (D-Tacoma), the bill requires that new buildings constructed with water fountains must also contain bottle filling stations; phases out the use of small personal health or beauty products in plastic containers that are provided by hotels and other lodging establishments; and bans the sale of soft plastic foam floats and docks, whilst mandating the study of hard-shelled plastic overwater structures. To achieve its goals, the bill engages multiple government agencies and councils and will be implemented along differing timelines. Rep. Mena championed HB 1085 as part of Washington State’s essential fight to protect public health, water resources, and salmon fisheries from excessive plastic pollution.

California State Water Resources Control Board. (2020, June 16). State Water Board addresses microplastics in drinking water to encourage public water system awareness [Press release]. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/press_room/press_releases/ 2020/pr06162020_microplastics.pdf

California is the first government entity in the world to systemically test its drinking water for microplastic contamination with the launch of its statewide testing apparatus. This initiative by the California State Water Resources Control Board is the result of 2018 Senate Bills No. 1422 and No. 1263, sponsored by Sen. Anthony Portantino, which, respectively, directed regional water providers to develop standardized methods for testing microplastic infiltration in freshwater and drinking water sources and set up monitoring of marine microplastics off California’s coast. As regional and state water officials voluntarily expand the testing and reporting of microplastic levels in drinking water over the next five years, the California government will continue to rely on the scientific community to further research the human and environmental health impacts of microplastic ingestion.

Back to top

2.2 National Policies

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023, April). Draft National Strategy to Prevent Plastic Pollution. EPA Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery. https://www.epa.gov/circulareconomy/draft-national-strategy-prevent-plastic-pollution

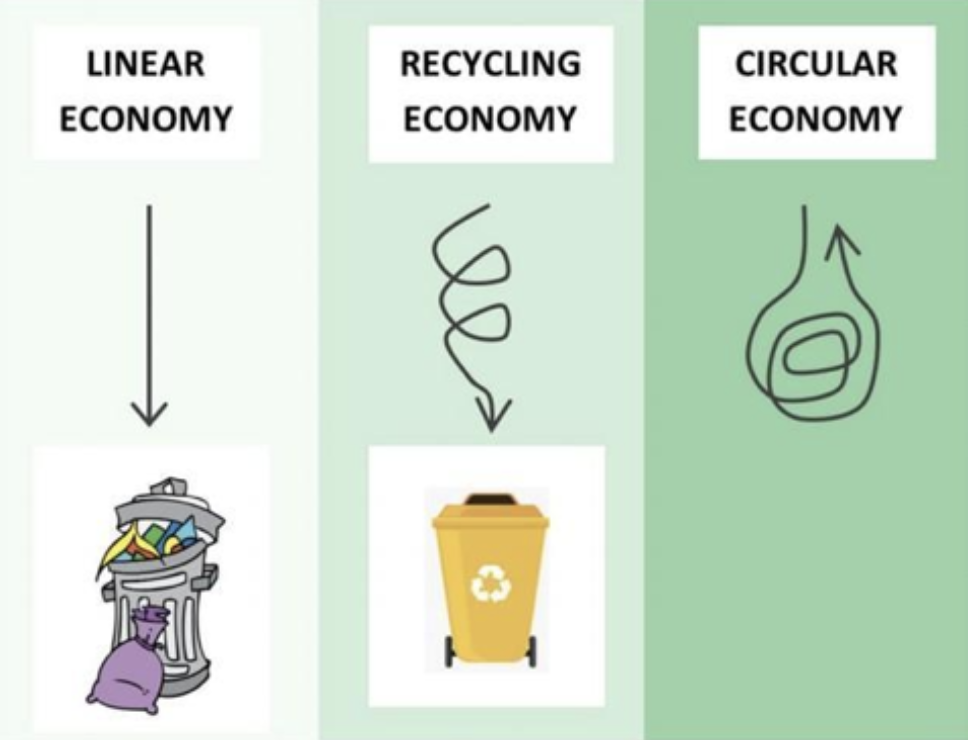

The strategy aims to reduce pollution during plastic production, improve post-use materials management, and prevent trash and micro/nano-plastics from entering waterways and remove escaped trash from the environment. The draft version, crafted as an extension of the EPA’s National Recycling Strategy released in 2021, emphasizes the need for a circular approach for plastics management and for significant action. The national strategy, while not yet enacted, provides guidance for federal and state-level policies and for other groups looking to address plastic pollution.

Jain, N., and LaBeaud, D. (2022, October) How Should U.S. Health Care Lead Global Change in Plastic Waste Disposal. AMA Journal of Ethics. 24(10):E986-993. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2022.986.

To date, the United States has not been at the forefront of policy regarding plastic pollution, but one way in which the U.S. could take the lead is regarding plastic waste disposal from health care. Disposal of health care waste is one of the biggest threats to global sustainable health care. Current practices of dumping domestic and international health care waste both on land and at sea, a practice which also undermines global health equity by adversely affecting the health of vulnerable communities. The authors suggest reframing social and ethical responsibility for health care waste production and management by assigning strict accountability to health care organizational leaders, incentivizing circular supply chain implementation and maintenance, and encouraging strong collaborations across medical, plastic, and waste industries.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, November). National Recycling Strategy Part One of a Series on Building a Circular Economy for All. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/final-national-recycling-strategy.pdf

The National Recycling Strategy is focused on enhancing and advancing the national municipal solid waste (MSW) recycling system and with the goal to create a stronger, more resilient and cost-effective waste management and recycling system within the United States. The report’s objectives include improved markets for recycled commodities, increased collection and improvement of material waste management infrastructure, reduction of contamination in the recycled materials stream, and an increase in policies to support circularity. While recycling will not solve the issue of plastic pollution, this strategy can help to guide best practices for the movement toward a more circular economy. Of note, the final section of this report provides a wonderful summary of the work being done by federal agencies in the United States.

Bates, S. (2021, June 25). Scientists Use NASA Satellite Data to Track Ocean Microplastics From Space. NASA Earth Science News Team. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/esnt2021/scientists-use-nasa-satellite-data-to-track-ocean-microplastics-from-space

Researchers are also using current NASA satellite data to track the movement of microplastics in the ocean, using data from NASA’s Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS).

Law, K. L., Starr, N., Siegler, T. R., Jambeck, J., Mallos, N., & Leonard, G. B. (2020). The United States’ contribution of plastic waste to land and ocean. Science Advances, 6(44). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd0288

This 2020 scientific study demonstrates that, in 2016, the U.S. generated more plastic waste by weight and per capita than any other nation. A sizable portion of this waste was illegally dumped in the U.S., and even more was inadequately managed in countries that imported materials collected in the U.S. for recycling. Accounting for these contributions, the amount of plastic waste generated in the U.S. estimated to enter the coastal environment in 2016 was up to five times larger than that estimated for 2010, rendering the country’s contribution among the highest in the world.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26132.

This assessment was conducted as a response to a request in the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act for a scientific synthesis of the U.S.’s contribution to and role addressing global marine plastic pollution. With the U.S. generating the largest amount of plastic waste of any country in the world as of 2016, this report calls for a national strategy to mitigate the U.S.’s plastic waste generation. It also recommends an expanded, coordinated monitoring system to better understand the scale and sources of U.S. plastic pollution and monitor the country’s progress.

Break Free From Plastic. (2021, March 26). Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act. Break Free From Plastic. http://www.breakfreefromplastic.org/pollution-act/

The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act of 2021 (BFFPPA) is a Federal bill sponsored by Sen. Jeff Merkley (OR) and Rep. Alan Lowenthal (CA that puts forth the most comprehensive set of policy solutions introduced in congress. The broad goals of the bill are to reduce plastic pollution from the source, increase recycling rates, and protect frontline communities. This bill will help protect low-income communities, communities of color, and Indigenous communities from their increased pollution risk by reducing plastic consumption and production. The bill will improve human health, by reducing our risk of ingesting microplastics. Breaking free from plastic would also drastically lower our greenhouse gas emissions. While the bill did not pass, it is important to include in this research page as an example for future comprehensive plastic laws at the national level in the United States.

Text – S. 1982 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Save Our Seas 2.0 Act (2020, December 18). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1982

In 2020, Congress enacted the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act which established requirements and incentives to reduce, recycle, and prevent marine debris (e.g., plastic waste). Of note the bill also established the Marine Debris Foundation, a charitable and nonprofit organization and is not an agency or establishment of the United States. The Marine Debris Foundation will work in partnership with NOAA’s Marine Debris Program and focus on activities to assess, prevent, reduce, and remove marine debris and address the adverse impacts of marine debris and its root causes on the economy of the United States, the marine environment (including waters in the jurisdiction of the United States, the high seas, and waters in the jurisdiction of other countries), and navigation safety.

S.5163 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Protecting Communities from Plastics Act. (2022, December 1). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/5163

In 2022, Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA) joined Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Rep. Alan Lowenthal (D-CA) to introduce the Protecting Communities from Plastics Act legislation. Building on key provisions from the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, this bill aims to address the plastic production crisis that disproportionately affects the health of low-wealth neighborhoods and communities of color. Driven by the larger goal of shifting the U.S. economy away from single-use plastic, the Protecting Communities from Plastics Act aims to establish stricter rules for petrochemical plants and create new nationwide targets for plastic source reduction and reuse in the packaging and food service sectors.

S.2645 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Rewarding Efforts to Decrease Unrecycled Contaminants in Ecosystems Act of 2021. (2021, August 5). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2645

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) introduced a new bill to create a powerful new incentive to recycle plastic, cut down on virgin plastic production, and hold the plastics industry more accountable for the toxic waste that insidiously undermines public health and vital environmental habitats. The proposed legislation, entitled the Rewarding Efforts to Decrease Unrecycled Contaminants in Ecosystems (REDUCE) Act, would impose a 20-cent per pound fee on the sale of virgin plastic employed in single-use products. This fee will help recycled plastics compete with virgin plastics on more equal footing. The items covered include packaging, food service products, beverage containers, and bags – with exemptions for medical products and personal hygiene products.

Jain, N., & LaBeaud, D. (2022). How Should US Health Care Lead Global Change in Plastic Waste Disposal? AMA Journal of Ethics, 24(10):E986-993. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2022.986.

Current disposal methods of plastic health care waste severely undermines global health equity, disproportionately impacting the health of vulnerable and marginalized populations. By continuing the practice of exporting domestic health care waste to be dumped into the land and waters of developing nations, the U.S. is amplifying the downstream environmental and health impacts that threaten global sustainable healthcare. A drastic reframing of social and ethical responsibility for plastic health care waste production and management is needed. This article recommends assigning strict accountability to health care organizational leaders, incentivizing circular supply chain implementation and maintenance, and encouraging strong collaborations across medical, plastic, and waste industries.

Wong, E. (2019, May 16). Science on the Hill: Solving the Plastic Waste Problem. Springer Nature. Retrieved from: bit.ly/2HQTrfi

A collection of articles connecting scientific experts to lawmakers on Capitol Hill. They address how plastic waste is a threat and what can be done to solve the problem while boosting businesses and leading to job growth.

BACK TO TOP

3. International Policies

Nielsen, M. B., Clausen, L. P., Cronin, R., Hansen, S. F., Oturai, N. G., & Syberg, K. (2023). Unfolding the science behind policy initiatives targeting plastic pollution. Microplastics and Nanoplastics, 3(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43591-022-00046-y

The authors analyzed six key policy initiatives targeting plastic pollution and found that plastic initiatives frequently refer to evidence from scientific articles and reports. The scientific articles and reports provide knowledge about plastic sources, ecological impacts of plastics and production and consumption patterns. More than half of the plastic policy initiatives examined refer to litter monitoring data. A rather diverse group of different scientific articles and tools seem to have been applied when shaping the plastic policy initiatives. However, there is still a lot of uncertainty related to determining the harm from plastic pollution, which implies that policy initiatives must allow for flexibility. Overall, scientific evidence is accounted for when shaping policy initiatives. The many different types of evidence used to support policy initiatives may result in conflicting initiatives. This conflict may affect international negotiations and policies.

OECD (2022, February), Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/de747aef-en.

While plastics are extremely useful materials for modern society, plastics production and waste generation continue to increase and urgent action is needed to make the lifecycle of plastics more circular. Globally, only 9% of plastic waste is recycled while 22% is mismanaged. The OECD calls for an expansion of national policies and improved international co-operation to mitigate environmental impacts all along the value chain. This report is focused on educating and supporting policy efforts to combat plastic leakage. The Outlook identifies four key levers for bending the plastics curve: stronger support for recycled (secondary) plastics markets; policies to boost technological innovation in plastics; more ambitious domestic policy measures; and greater international cooperation. This is the first of two planned reports, the second report, Global Plastics Outlook: Policy Scenarios to 2060 is listed below.

OECD (2022, June), Global Plastics Outlook: Policy Scenarios to 2060. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aa1edf33-en.

The world is nowhere close to achieving its objective of ending plastic pollution, unless more stringent and coordinated policies are implemented. To help achieve the goals set forth by various countries the OECD proposes a plastics outlook and policy scenarios to help guide policymakers. The report presents a set of coherent projections on plastics to 2060, including plastics use, waste as well as the environmental impacts linked to plastics, especially leakage to the environment. This report is the follow-up to the first report, Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options (listed above) which quantified current trends in plastics use, waste generation and leakage, as well as identified four policy levers to curb the environmental impacts of plastics.

IUCN. (2022). IUCN Briefing for Negotiators: Plastics Treaty INC. IUCN WCEL Agreement on Plastic Pollution Task Force. https://www.iucn.org/our-union/commissions/group/iucn-wcel-agreement-plastic-pollution-task-force/resources

The IUCN created a series of briefs, each less than five pages, to support the first round of negotiations for the Plastic Pollution Treaty as put forth by the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) resolution 5/14, The briefs were tailored to specific sessions and were built on steps taken over the last year regarding the treaty’s definitions, core elements, interactions with other treaties, potential structures and legal approaches. All briefs, including those on key terms, the circular economy, regime interactions, and multilateral environmental agreements are available here. These briefs are not only helpful for policymakers, but helped guide the development of the plastics treaty during the initial discussions.

The Last Beach Cleanup. (2021, July). Country Laws on Plastic Products. lastbeachcleanup.org/countrylaws

A comprehensive list of global laws relating to plastic products. To date, 188 countries have a nationwide plastic bag ban or pledged end date, 81 countries have a nationwide plastic straw ban or pledged end date, and 96 countries have a plastic foam container ban or pledged end date.

Buchholz, K. (2021). Infographic: The Countries Banning Plastic Bags. Statista Infographics. https://www.statista.com/chart/14120/the-countries-banning-plastic-bags/

Sixty-nine countries around the world have full or partial bans on plastic bags. Another thirty-two countries charge a fee or tax in order to limit plastic. China recently announced it will ban all non-compostable bags in major cities by the end of 2020 and extend the ban to the entire country by 2022. Plastic bags are just one step toward ending single use plastic dependency, but more comprehensive legislation is necessary to combat the plastics crisis.

Directive (EU) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment. PE/11/2019/REV/1 OJ L 155, 12.6.2019, p. 1–19 (BG, ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, GA, HR, IT, LV, LT, HU, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SL, FI, SV). ELI: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/904/oj

The steady increase in plastic waste generation and the leakage of plastic waste into the environment, in particular into the marine environment, must be tackled in order to achieve a circular life cycle for plastics. This law bans 10 kinds of single-use plastic and applies to certain SUP products, products made from oxo-degradable plastic and fishing gear containing plastic. It places market restrictions on plastic cutlery, straws, plates, cups and sets a collection target of 90% recycling for SUP plastic bottles by 2029. This ban on single-use plastics has already begun to have an effect on the way consumers use plastic and will hopefully lead to significant reductions in plastic pollution over the next decade.

Global Plastics Policy Centre (2022). A global review of plastics policies to support improved decision making and public accountability. March, A., Salam, S., Evans, T., Hilton, J., and Fletcher, S. (editors). Revolution Plastics, University of Portsmouth, UK. https://plasticspolicy.port.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/GPPC-Report.pdf

In 2022, the Global Plastics Policy Centre released an evidence-based study assessing the effectiveness of 100 plastics policies implemented by businesses, governments, and civil societies across the globe. This report details those findings– identifying critical gaps in evidence for each policy, evaluating factors that inhibited or enhanced policy performance, and synthesizing each analysis to highlight successful practices and key conclusions for policymakers. This in-depth review of world-wide plastic policies is an extension of the Global Plastic Policy Centre’s bank of independently analyzed plastics initiatives, the first of its kind that functions as a significant educator and informant on effective plastic pollution policy.

Royle, J., Jack, B., Parris, H., Hogg, D., & Eliot, T. (2019). Plastic Drawdown: A new approach to addressing plastic pollution from source to ocean. Common Seas. https://commonseas.com/uploads/Plastic-Drawdown-%E2%80%93-A-summary-for-policy-makers.pdf

The Plastic Drawdown model consists of four steps: modeling a country’s plastic waste generation and composition, mapping the path between plastic use and leakage into the ocean, analysis of the impact of key policies, and facilitates building consensus around key policies across government, community, and business stakeholders. There are eighteen different policies analyzed in this document, each discussing how they work, success level (effectiveness), and which macro and/or microplastics it addresses.

United Nations Environment Programme (2021). From Pollution to Solution: A global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution. United Nations, Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.unep.org/resources/pollution-solution-global-assessment-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution

This global assessment examines the magnitude and severity of marine litter and plastic pollution in all ecosystems and their catastrophic impacts on human and environmental health. It provides a comprehensive update on current knowledge and research gaps concerning plastic pollution’s direct effects on marine ecosystems, threats to global health, as well as the social and economic costs of ocean debris. Overall, the report strives to inform and prompt urgent, evidence-based action at all levels across the globe.

BACK TO TOP

3.1 Global Treaty

United Nations Environment Programme. (2022, March 2). What You Need to Know about the Plastic Pollution Resolution. United Nations, Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/what-you-need-know-about-plastic-pollution-resolution

One of the most reliable websites for information and updates on the Global Treaty, the United Nations Environment Programme is one of the most accurate sources for news and updates. This website announced the historic resolution at the resumed fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2) in Nairobi to end plastic pollution and forge an international legally binding agreement by 2024. Other items listed on the page include links to a document on Frequently Asked Questions regarding the Global Treaty and recordings of the UNEP’s resolutions moving the treaty forward, and a toolkit on plastic pollution.

IISD (2023, March 7). Summary of the Fifth Resumed Sessions of the Open Ended Committee of Permanent Representatives and the United Nations Environment Assembly and the Commemoration of UNEP@50: 21 February – 4 March 2022. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 16, No 166. https://enb.iisd.org/unea5-oecpr5-unep50

The fifth session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2), which convened under the theme “Strengthening Actions for Nature to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals,” was reported by in the Earth Negotiations Bulletin a publication by UNEA which acts as the reporting service for environmental and development negotiations. This particular bulletin covered UNEAS 5.2 and is an incredible resource for those looking to understand more about UNEA, the 5.2 resolution to “End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument” and other resolutions discussed in the meeting.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023, December). First Session of Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee on Plastic Pollution. United Nations Environment Programme, Punta del Este, Uruguay. https://www.unep.org/events/conference/inter-governmental-negotiating-committee-meeting-inc-1

This webpage details the first meeting of the intergovernmental negotiating committee (INC) held at the end of 2022 in Uruguay. It covers the first session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Additionally links to recordings of the meeting are available via YouTube links as well as information on policy briefing sessions and PowerPoints from the meeting. These recordings are all available in English, French, Chinese, Russian, and Spanish.

Andersen, I. (2022, March 2). A Lead Forward for Environmental Action. Speech for: High level segment of the Resumed Fifth Environment Assembly. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/leap-forward-environmental-action

The Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), said the agreement is the most important international multilateral environmental deal since the Paris climate accord in his speech advocating for passing the resolution to begin work on the Global Plastics Treaty. He argued that the agreement will only truly count if it has clear provisions that are legally binding, as the resolution states and must adopt a full life-cycle approach. This speech does an excellent job of covering the need for a Global Treaty and the United Nations Environment Programme’s priorities as negotiations continue.

IISD (2022, December 7). Summary of the First Meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution: 28 November – 2 December 2022. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol 36, No. 7. https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environment-negotiating-committee-inc1

Meeting for the first time, the intergovernmental negotiating committee (INC), Member States agreed to negotiate an international legally binding instrument (ILBI) on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, setting an ambitious timeline to conclude negotiations in 2024. As noted above, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin is a publication by UNEA which acts as the reporting service for environmental and development negotiations.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). Second Session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution: 29 May – 2 June 2023. https://www.unep.org/events/conference/second-session-intergovernmental-negotiating-committee-develop-international

Resource to be updated following the conclusion of the 2nd session in June 2023.

Ocean Plastics Leadership Network. (2021, June 10). The Global Plastics Treaty Dialogues. YouTube. https://youtu.be/GJdNdWmK4dk.

A dialogue began through a series of global online summits in preparation for the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) decision in February 2022 on whether to pursue a global agreement for plastics. The Ocean Plastics Leadership Network (OPLN) a 90-member activist-to-industry organization is pairing with Greenpeace and WWF to produce the effective dialogue series. Seventy-one countries are calling for a global plastics treaty alongside NGOs, and 30 major companies. Parties are calling for clear reporting on plastics throughout their lifecycle to account for everything being made and how it is handled, but there are still huge disagreement gaps remaining.

Parker, L. (2021, June 8). Global treaty to regulate plastic pollution gains momentum. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/global-treaty-to-regulate-plastic-pollution-gains-momentum

Globally there are seven definitions of what is considered a plastic bag and that comes with varying legislation for every country. The agenda of the global treaty is centered around finding a consistent set of definitions and standards, coordination of national targets and plans, agreements on reporting standards, and the creation of a fund to help finance waste management facilities where they are most needed in less developed countries.

World Wildlife Foundation, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, & Boston Consulting Group. (2020). The Business Case for a UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution. WWF, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, and BCG. https://f.hubspotusercontent20.net/hubfs/4783129/ Plastics/UN%20treaty%20plastic%20poll%20report%20a4_ single_pages_v15-web-prerelease-3mb.pdf

International corporations and businesses are called to support a global plastics treaty, because plastic pollution will affect the future of businesses. Many companies are facing reputational risks, as consumers become more aware of plastic risks and demand transparency surrounding the plastic supply chain. Employees want to work at companies with a positive purpose, investors are looking for forward thinking environmental sound companies, and regulators are promoting policies to tackle the plastic problem. For businesses, a UN treaty on plastic pollution will reduce operational complexity and varying legislation across market locations, simplify reporting, and help improve prospects to meet ambitious corporate goals. This is the chance for leading global companies to be at the forefront of policy change for the betterment of our world.

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2020, June). Convention on Plastic Pollution: Toward a New Global Agreement to Address Plastic Pollution. Environmental Investigation Agency and Gaia. https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Convention-on-Plastic-Pollution-June- 2020-Single-Pages.pdf.

The member states to the Plastics Conventions identified 4 main areas where a global framework is necessary: monitoring/reporting, plastic pollution prevention, global coordination, and technical/financial support. Monitoring and Reporting will be based on two indicators: a top-down approach of monitoring current plastic pollution, and a bottom-up approach of leakage data reporting. Creating global methods of standardized reporting along the plastics life-cycle will foster a transition to a circular economic structure. Plastic pollution prevention will help inform national action plans, and address specific issues like microplastics and standardization across the plastic value chain. International coordination on sea-based sources of plastic, waste trade, and chemical pollution will help increase biodiversity while expanding cross-regional knowledge exchange. Lastly, technical and financial support will increase scientific and socio-economic decision making, meanwhile assisting the transition for developing countries.

BACK TO TOP

3.2 Science Policy Panel

United Nations. (2023, January – February). Report of the second part of the first session of the ad hoc open-ended working group on a science-policy panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution. Ad hoc open-ended working group on a science-policy panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution First session Nairobi, 6 October 2022 and Bangkok, Thailand. https://www.unep.org/oewg1.2-ssp-chemicals-waste-pollution

The United Nation’s ad hoc open-ended working group (OEWG) on a science-policy panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution was held in Bangkok, from 30 January to 3 February 2023. During the meeting, resolution 5/8, the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) decided that a science-policy panel should be established to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution. UNEA further decided to convene, subject to the availability of resources, an OEWG to prepare proposals for the science-policy panel, to begin work in 2022 with the ambition of completing it by the end of 2024. The final report from the meeting can be found here.

Wang, Z. et al. (2021) We need a global science-policy body on chemicals and waste. Science. 371(6531) E:774-776. DOI: 10.1126/science.abe9090 | Alternative link: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abe9090

Many countries and regional political unions have regulatory and policy frameworks for managing chemicals and waste associated with human activities to minimize harms to human health and the environment. These frameworks are complemented and expanded by joint international action, particularly related to pollutants that undergo long-range transport via air, water, and biota; move across national borders through international trade of resources, products, and waste; or are present in many countries (1). Some progress has been made, but the Global Chemicals Outlook (GCO-II) from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (1) has called for “strengthen[ing] the science-policy interface and the use of science in monitoring progress, priority-setting, and policy-making throughout the life cycle of chemicals and waste.” With the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) soon meeting to discuss how to strengthen the science-policy interface on chemicals and waste (2), we analyze the landscape and outline recommendations for establishing an overarching body on chemicals and waste.

United Nations Environment Programme (2020). Assessment of Options for Strengthening the Science-Policy Interface at the International Level for the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/33808/ OSSP.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The urgent need to strengthen the science-policy interface at all levels to support and promote science-based local, national, regional and global action on sound management of chemicals and waste beyond 2020; use of science in monitoring progress; priority setting and policy making throughout the life cycle of chemicals and waste, taking into account the gaps and scientific information in developing countrie.

Fadeeva, Z., & Van Berkel, R. (2021, January). Unlocking circular economy for prevention of marine plastic pollution: An exploration of G20 policy and initiatives. Journal of Environmental Management. 277(111457). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111457

There is a growing global recognition of marine litter and rethink our approach to plastic and packaging, and outlines measures for enabling a transition to a circular economy that would fight single-use plastics and their negative externalities. These measures take the form of a policy proposal for G20 countries.

BACK TO TOP

3.3 Basel Convention Plastic Waste Amendments

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). The Basel Convention. United Nations. http://www.basel.int/Implementation/Plasticwaste/Overview/ tabid/8347/Default.aspx

This action was spurred by the Conference of the Parties to the Basel Convention adopted decision BC-14/12 by which it amended Annexes II, VIII and IX to the Convention in relation to plastic waste. Helpful links include a new story map on ‘Plastic waste and the Basel Convention’ which provides data visually through videos and infographics to explain the role of the Basel Convention Plastic Waste Amendments in controlling transboundary movements, advancing environmentally sound management, and promoting prevention and minimization of the generation of plastic waste.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). Controlling Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. The Basel Convention. United Nations. http://www.basel.int/Implementation/Plasticwastes/PlasticWaste Partnership/tabid/8096/Default.aspx

A Plastic Waste Partnership (PWP) has been established under the Basel Convention, to improve and promote the environmentally sound management (ESM) of plastic waste and to prevent and minimize its generation. The program has overseen or supported 23 pilot projects to spur action. These projects are intended to promote waste prevention, improve waste collection, address transboundary movements of plastic waste, and provide education and raise awareness of plastic pollution as a hazardous material.

Benson, E. & Mortsensen, S. (2021, October 7). The Basel Convention: From Hazardous Waste to Plastic Pollution. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/basel-convention-hazardous-waste-plastic-pollution

This article does a good job of explaining the basics of the Basel convention for a general audience. The CSIS report covers the establishment of the Basel Convention in the 1980s to address toxic waste. the Basel Convention was signed by 53 states and the European Economic Community (EEC) to help regulate the trade of hazardous waste and to mitigate the unwanted transport of toxic shipments that governments did not consent to receiving. The article further provides information via a series of questions and answers including who has signed the agreement, what will the effects of a plastic amendment, and what comes next. The initial Basel framework has created a launching point to address the consistent disposal of waste, though this is only part of a larger strategy needed to truly achieve a circular economy.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022, June 22). New International Requirements for the Export and Import of Plastic Recyclables and Waste. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/hwgenerators/new-international-requirements-export-and-import-plastic-recyclables-and-waste

In May of 2019, 187 countries restricted international trade in plastic scraps/recyclables through the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. Starting on January 1st, 2021 recyclables and waste are only allowed to be shipped to countries with the prior written consent of the importing country and any transit countries. The United States is not a current party of the Basel Convention, meaning that any country that is a signatory to the Basel Convention cannot trade Basel-restricted waste with the U.S. (a nonparty) in absence of predetermined agreements between countries. These requirements aim to address the improper disposal of plastic waste and reduce transit leakage into the environment. It has been common practice for developed nations to send their plastic to developing countries, but the new restrictions are making this harder.

BACK TO TOP

4. Circular Economy

Gorrasi, G., Sorrentino, A., & Lichtfouse, E. (2021). Back to plastic pollution in COVID times. Environmental Chemistry Letters. 19(pp.1-4). HAL Open Science. https://hal.science/hal-02995236

The chaos and urgency induced by the COVID-19 pandemic led to massive fossil fuel-derived plastic production that largely ignored standards outlined in environmental policies. This article emphasizes that solutions for a sustainable and circular economy require radical innovations, consumer education and most importantly political willingness.

Center for International Environmental Law. (2023, March). Beyond Recycling: Reckoning with Plastics in a Circular Economy. Center for International Environmental Law. https://www.ciel.org/reports/circular-economy-analysis/

Written for policy makers, this report argues for more consideration to be made when crafting laws regarding plastic. In particular the author’s argue that more should be done in regards to the toxicity of plastic, it should be acknowledged that burning plastic is not a part of the circular economy, that safe design can be considered circular, and that upholding human rights is necessary to achieve a circular economy. policies or technical processes that require the continuation and expansion of plastics production cannot be labeled circular, and they should thus not be considered solutions to the global plastics crisis. Finally, the author’s argue that any new global agreement on plastics, for instance, must be predicated on restrictions on plastics production and the elimination of toxic chemicals in the plastics supply chain.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2022, November 2). The Global Commitment 2022 Progress Report. United Nations Environment Programme. https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/f6oxost9xeso-nsjoqe/@/#

The assessment found that the goals set by companies to achieve a 100% reusable, recyclable, or compostable packaging by 2025 will almost certainly not be met and will miss key 2025 targets for a circular economy. The report noted that strong progress is being made, but the prospect of not meeting targets reinforces the need to accelerate action and argues for the decoupling of business growth from packaging usage with an immediate action needed by governments to spur change. This report is a key feature for those looking to understand the current state of company commitments to reducing plastic while providing the criticism needed for businesses to take further action.

Greenpeace. (2022, October 14). Circular Claims Fall Flat Again. Greenpeace Reports. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/circular-claims-fall-flat-again/

As an update to Greenpeace’s 2020 Study, the authors review their previous claim that the economic driver for collecting, sorting, and reprocessing post-consumer plastic products is likely to worsen as plastic production increases. The authors find that over the last two years this claim has been proven true with only some types of plastic bottles being legitimately recycled. The paper then discussed reasons why mechanical and chemical recycling fail including how wasteful and toxic the recycling process is and that it is not economical. Significantly more action needs to take place immediately to address the growing problem of plastic pollution.

Hocevar, J. (2020, February 18). Report: Circular Claims Fall Flat. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Greenpeace-Report-Circular-Claims-Fall-Flat.pdf

An analysis of the current plastic waste collection, sorting, and reprocessing in the U.S. to determine if products could legitimately be called “recyclable”. The analysis found that almost all common plastic pollution items, including single-use foodservice and convenience products, cannot be recycled for various reasons from municipalities collecting but not recycling to plastic shrink sleeves on bottles making them unrecyclable. See above for the updated 2022 report.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, November). National Recycling Strategy Part One of a Series on Building a Circular Economy for All. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/final-national-recycling-strategy.pdf

The National Recycling Strategy is focused on enhancing and advancing the national municipal solid waste (MSW) recycling system and with the goal to create a stronger, more resilient and cost-effective waste management and recycling system within the United States. The report’s objectives include improved markets for recycled commodities, increased collection and improvement of material waste management infrastructure, reduction of contamination in the recycled materials stream, and an increase in policies to support circularity. While recycling will not solve the issue of plastic pollution, this strategy can help to guide best practices for the movement toward a more circular economy. Of note, the final section of this report provides a wonderful summary of the work being done by federal agencies in the United States.

Beyond Plastics (2022, May). Report: The Real Truth About the U.S. Plastics Recycling Rate. The Last Beach Cleanup. https://www.lastbeachcleanup.org/_files/ ugd/dba7d7_9450ed6b848d4db098de1090df1f9e99.pdf

The current 2021 U.S. plastic recycling rate is estimated to be between 5 and 6%. Factoring in additional losses that aren’t measured, such as plastic waste collected under the pretense of “recycling” that are burned, instead, the U.S.’s true plastic recycling rate may be even lower. This is significant as rates for cardboard and metal are significantly higher. The report then provides an astute summary of the history of plastic waste, exports, and recycling rates in the United States and argues for actions that reduce the amount of plastic consumed such as bans on single-use plastic, water refill stations, and reusable container programs.

New Plastics Economy. (2020). A Vision of a Circular Economy for Plastic. PDF

The six characteristics needed to achieve a circular economy are: (a) elimination of problematic or unnecessary plastic; (b) items are reused to reduce the need for single-use plastic; (c) all plastic must be reusable, recyclable, or compostable; (d) all packaging is reused, recycled, or composted in practice; (e) plastic is decoupled from the consumption of finite resources; (f) all plastic packaging is free of hazardous chemicals and the rights of all people are respected. The straightforward document is a quick read for anyone interested in best approaches to the circular economy without extraneous detail.

Fadeeva, Z., & Van Berkel, R. (2021, January). Unlocking circular economy for prevention of marine plastic pollution: An exploration of G20 policy and initiatives. Journal of Environmental Management. 277(111457). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111457

There is a growing global recognition of marine litter and rethink our approach to plastic and packaging, and outlines measures for enabling a transition to a circular economy that would fight single-use plastics and their negative externalities. These measures take the form of a policy proposal for G20 countries.

Nunez, C. (2021, September 30). Four key ideas to building a circular economy. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/paid-content-four-key-ideas-to-building-a-circular-economy-for-plastics

Experts across sectors agree that we can create a more efficient system where materials are repeatedly reused. In 2021, the American Beverage Association (ABA) virtually convened a group of experts, including environmental leaders, policymakers, and corporate innovators, to discuss the role of plastic in consumer packaging, future manufacturing, and recycling systems, with the larger framework being the consideration of adaptable circular economy solutions.

Meys, R., Frick, F., Westhues, S., Sternberg, A., Klankermayer, J., & Bardow, A. (2020, November). Towards a circular economy for plastic packaging wastes – the environmental potential of chemical recycling. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 162(105010). DOI: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105010.

Keijer, T., Bakker, V., & Slootweg, J.C. (2019, February 21). Circular chemistry to enable a circular economy. Nature Chemistry. 11(190-195). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0226-9

To optimize resource efficiency and enable a closed-loop, waste-free chemical industry, the linear consume then dispose economy must be replaced. To do this, a product’s sustainability considerations should include its entire lifecycle and aim to replace the linear approach with circular chemistry.

Spalding, M. (2018, April 23). Don’t Let Plastic Get into the Ocean. The Ocean Foundation. earthday.org/2018/05/02/dont-let-the-plastic-get-into-the-ocean

The keynote done for the Dialogue for Ending Plastic Pollution at the Embassy of Finland frames the issue of plastic in the ocean. Spalding discusses the problems of plastics in the ocean, how single-use plastics play a role, and where the plastics come from. Prevention is key, don’t be part of the problem, and personal action are a good start. Reuse and reduction of waste is also essential.

Back to top

5. Green Chemistry

Tan, V. (2020, March 24). Are Bio-plastics a Sustainable Solution? TEDx Talks. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Kjb7AlYOSgo.

Bio-plastics can be solutions to petroleum based plastic production, but bioplastics do not stop the plastic waste problem. Bioplastics are currently more expensive and less readily available compared to petroleum-based plastics. Further, bioplastics are not necessarily better for the environment than petroleum-based plastics as some bioplastics will not naturally degrade in the environment. Bioplastics alone cannot solve our plastic problem, but they can be part of the solution. We need more comprehensive legislation and guaranteed implementation that covers plastic production, consumption, and disposal.

Tickner, J., Jacobs, M. and Brody, C. (2023, February 25). Chemistry Urgently Needs to Develop Safer Materials. Scientific American. www.scientificamerican.com/article/chemistry-urgently-needs-to-develop-safer-materials/

The authors argue that if we are to end the dangerous chemical incidents that make people and ecosystems sick, we need to address human kind’s dependence on these chemicals and the manufacturing processes needed to create them. What is needed are cost-effective, well performing, and sustainable solutions.

Neitzert, T. (2019, August 2). Why compostable plastics may be no better for the environment. The Conversation. theconversation.com/why-compostable-plastics-may-be-no-better-for-the-environment-100016

As the world is shifting away from single-use plastics, new biodegradable or compostable products seem to be better alternatives to plastic, but they may be just as bad for the environment. A lot of the problem lies with the terminology, lack of recycling or composting infrastructures, and the toxicity of degradable plastics. The whole product lifecycle needs to be analyzed before it is labeled as a better alternative to plastic.

Gibbens, S. (2018, November 15). What You Need to Know about Plant-based Plastics. National Geographic. nationalgeographic.com.au/nature/what-you-need-to-know-about-plant-based-plastics.aspx

At a glance, bioplastics seem like a great alternative to plastics, but the reality is more complicated. Bioplastic offers a solution to reduce burning fossil fuels, but may introduce more pollution from fertilizers and more land being diverted from food production. Bioplastics are also predicted to do little in stopping the amount of plastic entering the waterways.

Steinmark, I. (2018, November 5). Nobel Prize Awarded for Evolving Green Chemistry Catalysts. Royal Society of Chemistry. eic.rsc.org/soundbite/nobel-prize-awarded-for-evolving-green-chemistry-catalysts/3009709.article

Frances Arnold is one of this year’s Nobel Laureates in chemistry for her work in Directed Evolution (DE), a green chemistry biochemical hack in which proteins/enzymes are randomly mutated many times over, then screened to find out which ones work best. It could overhaul the chemical industry.

Greenpeace. (2020, September 9). Deception by the Numbers: American Chemistry Council claims about chemical recycling investments fail to hold up to scrutiny. Greenpeace. www.greenpeace.org/usa/research/deception-by-the-numbers

Groups, such as the American Chemistry Council (ACC), have advocated for chemical recycling as a solution to the plastic pollution crisis, but the viability of chemical recycling remains questionable. Chemical recycling or “advanced recycling” refers to plastic-to-fuel, waste-to-fuel, or plastic-to-plastic and uses various solvents to degrade plastic polymers into their basic building blocks. Greenpeace found that less than 50% of the ACC’s projects for advanced recycling were credible recycling projects and plastic-to-plastic recycling shows very little likelihood of success. To date taxpayers have provided at least $506 million in support of these projects of uncertain viability. Consumers and constituents should be aware of the problems of solutions – like chemical recycling – that will not solve the plastic pollution problem.

Back to top

6. Plastic and Ocean Health

Miller, E. A., Yamahara, K. M., French, C., Spingarn, N., Birch, J. M., & Van Houtan, K. S. (2022). A Raman spectral reference library of potential anthropogenic and biological ocean polymers. Scientific Data, 9(1), 1-9. DOI: 10.1038/s41597-022-01883-5

Microplastics have been found to extreme degrees in marine ecosystems and food webs, however, to solve this global crisis, researchers have created a system to identify the polymer composition. This process – led by the Monterey Bay Aquarium and MBARI (Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute) – will help trace the sources of plastic pollution through an open-access Raman spectral library. This is particularly significant as the cost of the methods place barriers on the library of polymer spectra for comparison. The researchers hope that this new database and reference library will help facilitate progress in the global plastic pollution crisis.

Zhao, S., Zettler, E., Amaral-Zettler, L., and Mincer, T. (2020, September 2). Microbial Carrying Capacity and Carbon Biomass of Plastic Marine Debris. The ISME Journal. 15, 67-77. DOI: 10.1038/s41396-020-00756-2

Ocean plastic debris has been found to transport living organisms across seas and to new areas. This study found that plastic presented substantial surface areas for microbial colonization and large quantities of biomass and other organisms have a high potential to affect biodiversity and ecological functions.

Abbing, M. (2019, April). Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Ocean Pollution. Island Press.

If the world continues on its current path, there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish by 2050. Worldwide, every minute there is the equivalent of a truckload of trash dumped into the ocean and that rate is on the rise. Plastic Soup looks at the cause and consequences of plastic pollution and what can be done to stop it.

Spalding, M. (2018, June). How to stop plastics polluting our ocean. Global Cause. globalcause.co.uk/plastic/how-to-stop-plastics-polluting-our-ocean/

Plastic in the ocean falls into three categories: marine debris, microplastics, and microfibres. All of these are devastating to marine life and kill indiscriminately. Every individual’s choices are important, more people need to opt for plastic substitutes because consistent behavior change helps.

Attenborough, Sir D. (2018, June). Sir David Attenborough: plastic and our oceans. Global Cause. globalcause.co.uk/plastic/sir-david-attenborough-plastic-and-our-oceans/

Sir David Attenborough discusses his appreciation for the ocean and how it is a vital resource that is “critical for our very survival.” The plastics issue could “hardly be more serious.” He says that people n6.1eed to think more about their plastic usage, treat plastic with respect, and “if you don’t need it, don’t use it.”

Back to top

6.1 Ghost Gear

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2023). Derelict Fishing Gear. NOAA Marine Debris Program. https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/types/derelict-fishing-gear

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines derelict fishing gear, sometimes called “ghost gear,” refers to any discarded, lost, or abandoned fishing gear in the marine environment. To address this problem, the NOAA Marine Debris Program has collected more than 4 million pounds of ghost gear, however, despite this significant collection ghost gear still makes up the largest portion of plastic pollution in the ocean, highlighting the need for more work to combat this threat to the marine environment.

Kuczenski, B., Vargas Poulsen, C., Gilman, E. L., Musyl, M., Geyer, R., & Wilson, J. (2022). Plastic gear loss estimates from remote observation of industrial fishing activity. Fish and Fisheries, 23, 22– 33. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12596

Scientists with The Nature Conservancy and the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), in partnership with the Pelagic Research Group and Hawaii Pacific University, published an expansive peer-reviewed study that gives the first ever global estimate of plastic pollution from industrial fisheries. In the study, Plastic gear loss estimates from remote observation of industrial fishing activity, scientists analyzed data collected from Global Fishing Watch and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to calculate the scale of industrial fishing activity. Combining this data with technical models of fishing gear and key input from industry experts, scientists were able to predict the upper and lower bounds of pollution from industrial fisheries. According to its findings, over 100 million pounds of plastic pollution enters the ocean each year from ghost gear. This study provides the important baseline information required to advance understanding of the ghost gear problem and begin adapting and executing the necessary reforms.

Giskes, I., Baziuk, J., Pragnell-Raasch, H. and Perez Roda, A. (2022). Report on good practices to prevent and reduce marine plastic litter from fishing activities. Rome and London, FAO and IMO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8665en

This report provides an overview of how abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) plagues aquatic and coastal environments and contextualizes its extensive impact and contribution to the broader global issue of marine plastic pollution. A key component to successfully addressing ALDFG, as outlined in this document, is heeding lessons learned from existing projects in other parts of the world, whilst recognizing that any management strategy may only be applied with great consideration of local circumstances/needs. This GloLitter report presents ten case studies that exemplify prime practices for the prevention, mitigation, and remediation of ALDFG.

Ocean Outcomes. (2021, July 6). Ghost Gear Legislation Analysis. Global Ghost Gear Initiative, World Wide Fund for Nature, and Ocean Conservancy. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/ 5b987b8689c172e29293593f/t/60e34e4af5f9156374d51507/ 1625509457644/GGGI-OC-WWF-O2-+LEGISLATION+ANALYSIS+REPORT.pdf

The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) launched in 2015 with the goal of stopping the deadliest form of ocean plastics. Since 2015, 18 national governments have joined the GGGI alliance signaling a desire from countries to address their ghost gear pollution. Currently, the most common policy on gear pollution prevention is gear marking, and the least commonly used policies are mandatory lost gear retrieval and national ghost gear action plans. Moving forward, the top priority needs to be the enforcement of existing ghost gear legislation. Like all plastic pollution, ghost gear requires international coordination to the transboundary plastic pollution issue.

World Wide Fund for Nature. (2020, October). Stop Ghost Gear: The Most Deadly Form of Marine Plastic Debris. WWF International. https://wwf.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Stop-Ghost-Gear_Advocacy-Report.pdf

According to the United Nations there are more than 640,000 tons of ghost gear in our ocean, making up 10% of all ocean plastic pollution. Ghost gear is a slow and painful death for many animals and the free floating gear can damage important nearshore and marine habitats. Fishers generally do not want to lose their gear, yet 5.7% of all fishing nets, 8.6% of traps and pots, and 29% of all fishing lines used globally are abandoned, lost, or discarded into the environment. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated deep-sea fishing is a considerable contributor to the amount of discarded ghost gear. There must be long-term strategically enforced solutions to develop effective gear loss prevention strategies. Meanwhile, it is important to develop non-toxic, safer gear designs to reduce destruction when lost at sea.

Global Ghost Gear Initiative. (2022). The Impact Of Fishing Gear As A Source Of Marine Plastic Pollution. Ocean Conservancy. https://Static1.Squarespace.Com/Static/5b987b8689c172e2929 3593f/T/6204132bc0fc9205a625ce67/1644434222950/ Unea+5.2_gggi.Pdf

This informational paper was prepared by the Ocean Conservancy and Global Ghost Gear Initiative to support negotiations in preparation for the 2022 United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA 5.2). Answering the questions of what is ghost gear, where does it originate, and why is it detrimental to ocean environments, this paper outlines the overall necessity for ghost gear to be included in any global treaty addressing marine plastic pollution.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2021). Collaborating Across Borders: The North American Net Collection Initiative. https://clearinghouse.marinedebris.noaa.gov/project?mode=View&projectId=2258

With support from the NOAA Marine Debris Program, the Ocean Conservancy’s Global Ghost Gear Initiative is coordinating with partners in Mexico and California to launch the North American Net Collection Initiative, the mission of which is to more effectively manage and prevent the loss of fishing gear. This cross-border effort will collect old fishing gear to be properly processed and recycled and also work alongside U.S. and Mexican fisheries to promote different recycling strategies and improve the overall management of used or retired gear. The project is anticipated to run from fall 2021 to summer 2023.

Charter, M., Sherry, J., & O’connor, F. (2020, July). Creating Business Opportunities From Waste Fishing Nets: Opportunities For Circular Business Models And Circular Design Related To Fishing Gear. Blue Circular Economy. Retrieved From Https://Cfsd.Org.Uk/Wp-Content/Uploads/2020/07/Final-V2-Bce-Master-Creating-Business-Opportunities-From-Waste-Fishing-Nets-July-2020.Pdf

Funded by the European Commission (EC) Interreg, Blue Circular Economy released this report to address the widespread and enduring problem of waste fishing gear in the ocean and propose related business opportunities within the Northern Periphery and Arctic (NPA) region. This assessment examines the implications that this problem creates for stakeholders in the NPA region, and provides a comprehensive discussion of new circular business models, the Extended Producer Responsibility scheme that is part of the EC’s Single Use Plastics Directive, and circular design of fishing gear.

The Hindu. (2020). Impact of ‘ghost’ fishing gears on ocean wildlife. YouTube. https://youtu.be/9aBEhZi_e2U.

A major contributor of marine life deaths is ghost gear. Ghost gear traps and entangles large marine wildlife for decades without human interference including threatened and endangered species of whales, dolphins, seals, sharks, turtles, rays, fish, etc. Trapped species also attract predators that are then killed while trying to hunt and consume entangled prey. Ghost gear is one of the most threatening types of plastic pollution, because it is designed for the trapping and killing of marine life.

Back to top

6.2 Effects on Marine Life

Eriksen, M., Cowger, W., Erdle, L. M., Coffin, S., Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Moore, C. J., Carpenter, E. J., Day, R. H., Thiel, M., & Wilcox, C. (2023). A growing plastic smog, now estimated to be over 170 trillion plastic particles afloat in the world’s oceans—Urgent solutions required. PLOS ONE. 18(3), e0281596. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281596

As more people become aware of the problem of plastic pollution, more data is needed to assess whether implemented policies are effective. The authors of this study work to address this gap in data using a global time-series that estimates the average counts and mass of small plastics in the ocean surface layer from 1979 to 2019. They found that today, there are approximately 82–358 trillion plastic particles weighing 1.1–4.9 million tonnes, for a total of over 171 trillion plastic particles floating in the world’s oceans. The authors of the study noted that there was no observed or detectable trend until 1990 when there was a rapid increase in the number of plastic particles until the present. This only highlights the need for strong actions to be taken as soon as possible to prevent the situation from accelerating further.

Pinheiro, L., Agostini, V. Lima, A, Ward, R., and G. Pinho. (2021, June 15). The Fate of Plastic Litter within Estuarine Compartments: An Overview of Current Knowledge for the Transboundary Issue to Guide Future Assessments. Environmental Pollution, Vol 279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116908

The role of rivers and estuaries in the transport of plastic is not fully understood, but they likely serve as a major conduit for oceanic plastic pollution. Microfibers remain the most common type of plastic, with new studies focusing on micro estuarine organisms, microfibers rising/sinking as determined by their polymer characteristics, and spatial-temporal fluctuations in prevalence. More analysis is needed specific to the estuarine environment, with special note of the socio-economic aspects that may affect management policies.

Brahney, J., Mahowald, N., Prank, M., Cornwall, G., Kilmont, Z., Matsui, H. & Prather, K. (2021, April 12). Constraining the atmospheric limb of the plastic cycle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118(16) e2020719118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020719118

Microplastic, including particles and fibers are now so common that plastic now has its own atmospheric cycle with plastic particles traveling from the Earth to the atmosphere and back again. The report found that microplastics found in the air in the area of study (the western United States) are primarily derived from secondary re-emission sources including roads (84%), the ocean (11%), and agricultural soil dust (5%). This study is especially noteworthy in that it draws attention to the growing concern over plastic pollution originating from roads and tires.

Back to top

6.3 Plastic Pellets (Nurdles)

Faber, J., van den Berg, R., & Raphaël, S. (2023, March). Preventing Spills of Plastic Pellets: A Feasibility Analysis of Regulatory Options. CE Delft. https://cedelft.eu/publications/preventing-spills-of-plastic-pellets/

Plastic pellets (also called ‘nurdles’) are small pieces of plastics, typically between 1 and 5 mm in diameter, produced by the petrochemical industry which serve as an input for the plastics industry to manufacture plastic products. With vast quantities of nurdles are transported via the sea and given that accidents occur, there have been significant examples of pellet leaks that end up polluting the marine environment. To address this the International Maritime Organization has created a subcommittee to consider regulations to address and manage pellet leaks.

Fauna & Flora International. (2022). Stemming the tide: putting an end to plastic pellet pollution. https://www.fauna-flora.org/app/uploads/2022/09/FF_Plastic_Pellets_Report-2.pdf

Plastic pellets are lentil-sized pieces of plastic that are melted together to create almost all plastic items in existence. As the feedstock for the global plastics industry, pellets are transported around the world and are a significant source of microplastic pollution; it is estimated that billions of individual pellets enter the ocean every year as a result of spills on land and at sea. To solve this problem the author’s argue for an urgent move towards a regulatory approach with mandatory requirements that are supported by rigorous standards and certification schemes.

Tunnell, J. W., Dunning, K. H., Scheef, L. P., & Swanson, K. M. (2020). Measuring plastic pellet (nurdle) abundance on shorelines throughout the Gulf of Mexico using citizen scientists: Establishing a platform for policy-relevant research. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 151(110794). DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110794

Many nurdles (small plastic pellets) were observed washing up on Texas beaches. A volunteer-driven citizen science project, “Nurdle Patrol,” was established. 744 volunteers have conducted 2042 citizen science surveys from Mexico to Florida. All 20 of the highest standardized nurdle counts were recorded at sites in Texas. Policy responses are complex, multi-scaled, and face obstacles.

Karlsson, T., Brosché, S., Alidoust, M. & Takada, H. (2021, December). Plastic pellets found on beaches all over the world contain toxic chemicals. International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). ipen.org/sites/default/files/documents/ipen-beach-plastic-pellets-v1_4aw.pdf

Plastics from all sampled locations contained all ten analyzed benzotriazole UV stabilizers, including UV-328. Plastics from all sampled locations also contained all thirteen analyzed polychlorinated biphenyls. The concentrations were especially high in African countries, even though they are not major producers of chemicals nor plastics. The results show that with plastic pollution there is also chemical pollution. The results also illustrate that plastics can play a very important role in the long-range transport of toxic chemicals.

Maes, T., Jefferies, K., (2022, April). Marine Plastic Pollution – are Nurdles a Special Case for Regulation?. GRID-Arendal. https://news.grida.no/marine-plastic-pollution-are-nurdles-a-special-case-for-regulation

Proposals to regulate the carriage of pre-production plastic pellets, called “nurdles,” are on the agenda for The International Maritime Organization Pollution Prevention and Response Sub-Committee (PPR). This brief provides an excellent background, defining nurdles, explaining how they get to the marine environment, and discussing the threats to the environment from nurdles. This is a good resource for both policy makers and the general public who would prefer a non-scientific explanation.

Bourzac, K. (2023, January). Grappling with the biggest marine plastic spill in history. C&EN Global Enterprise. 101 (3), 24-31. DOI: 10.1021/cen-10103-cover

In May 2021, the cargo ship, X-Press Pearl, caught fire and sank off the coast of Sri Lanka. The wreck unleashed a record 1,680 metric tons of plastic pellets and countless toxic chemicals off Sri Lanka’s shoreline. Scientists are studying the accident, the largest known marine plastic fire and spill, to help advance understanding of the environmental effects of this poorly-researched type of pollution. In addition to observing how nurdles break down over time, what kinds of chemicals leach in the process and the environmental impacts of such chemicals, scientists are specifically interested in addressing what happens chemically when plastic nurdles burn. In documenting changes in nurdles washed up on Sarakkuwa beach near the shipwreck, environmental scientist Meththika Vithanage found high levels of lithium in the water and on the nurdles (Sci. Total Environ. 2022, DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154374; Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114074). Her team also found high levels of other toxic chemicals, exposure to which can slow plant growth, damage tissues in aquatic animals, and cause organ failure in people. The wreck’s aftermath continues to play out in Sri Lanka, where economic and political challenges present hurdles for local scientists and may complicate efforts to ensure compensation for environmental damages, the scope of which remains unknown.

Bǎlan, S., Andrews, D., Blum, A., Diamond, M., Rojello Fernández, S., Harriman, E., Lindstrom, A., Reade, A., Richter, L., Sutton, R., Wang, Z., & Kwiatkowski, C. (2023, January). Optimizing Chemicals Management in the United States and Canada through the Essential-Use Approach. Environmental Science & Technology. 57 (4), 1568-1575 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.2c05932