Author: Mark J. Spalding

The recent issue of New Scientist cited “eels spawning” as one of the 11 things we know exist, but have never actually seen. It’s true—the origins and even much of the migratory patterns of the American and European eels are largely unknown until they arrive as baby eels (elvers) in the mouths of northern rivers each spring. Most of their life cycle plays out over the horizon of human observation. What we do know is that for these eels, just as for many other species, the Sargasso Sea is the place they need to thrive.

From March 20 to 22nd, the Sargasso Sea Commission met in Key West, Florida at the NOAA Eco-Discovery Center there. This is the first time that all of the Commissioners have been together since the most recent commissioners (including me) were announced last September.

So what is the Sargasso Sea Commission? It was created by what is known as the March 2014 “Hamilton Declaration,” which established the ecological and biological importance of the Sargasso Sea. The Declaration also expressed the idea that the Sargasso Sea needs special governance focused on conservation even though much of it is outside the boundaries of any nation’s jurisdiction.

Key West was in full spring break mode, which made for great people watching as we traveled back and forth to the NOAA center. Inside our meetings though, we were focused more on these key challenges than on sunscreen and margaritas.

- First, the 2 million square mile Sargasso Sea has no coastline to define its boundaries (and thus has no coastal communities to defend it). The map of the Sea excludes the EEZ of Bermuda (the nearest country), and thus it is outside the jurisdiction of any country in what we call the high seas.

- Second, lacking terrestrial boundaries, the Sargasso Sea is instead defined by currents that create a gyre, inside which sea life is abundant under mats of floating sargassum. Unfortunately, the same gyre helps trap plastics and other pollution that adversely affect the eels, fish, turtles, crabs, and other creatures that live there.

- Third, the Sea is not very well understood, either from a governance point of view or a scientific point of view, nor well known in its importance to fisheries and other ocean services far away.

The Commission’s agenda for this meeting was to review the accomplishments of the Secretariat for the Commission, hear some of the latest research about the Sargasso Sea, and to set priorities for the coming year.

The meeting began with an introduction to a mapping project called COVERAGE (CONVERAGE is CEOS (Committee on Earth Observation Satellites) Ocean Variable Arranging Research and Application for GEO (Group on Earth Observations)that was put together by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL CalTech). COVERAGE is intended to integrate all of the satellite observations including wind, currents, sea surface temperature and salinity, chlorophyll, color etc. and create a visualization tool to monitor conditions in the Sargasso Sea as a pilot for a global effort. The interface appears to be very user-friendly and will be available for us on the Commission to test drive in approximately 3 months. The NASA and JPL scientists were seeking our advice regarding data sets we would like to see and be able to overlay with the information already available from NASA’s satellite observations. Examples included ship tracking and tracking of tagged animals. The fishing industry, oil and gas industry, and the defense department already have such tools to help them meet their missions, thus this new tool is for policy makers, as well as natural resource managers.

The Commission and the NASA/JPL scientists then separated into concurrent meetings and for our part, we began with an acknowledgment of our Commission’s goals:

- the continued recognition of ecological and biological significance of the Sargasso Sea;

- the encouragement of scientific research to better understand the Sargasso Sea; and

- to develop proposals to submit to international, regional and sub-regional organizations in order to further the objectives of the Hamilton Declaration

We then reviewed the status of various pieces of our work plan, including:

- ecological importance and significance activities

- fisheries activities in front of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) and Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization

- shipping activities, including those in front of the International Maritime Organization

- seafloor cables and seabed mining activities, including those in front of the International Seabed Authority

- migratory species management strategies, including those in front of the Convention on Migratory Species and Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

- and finally the role of data and information management, and how it was to be integrated into management schemes

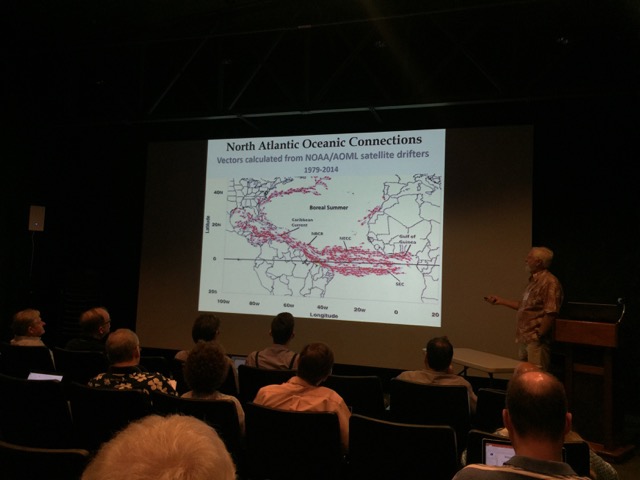

The Commission considered new topics, which included plastic pollution and marine debris in the gyre that defines the Sargasso Sea; and the role of the potential for changing ocean systems that may affect the path of the Gulf Current and other major currents that the form Sargasso Sea.

The Sea Education Association (WHOI) has a number of years of data from trawls to collect and examine plastic pollution in the Sargasso Sea. Preliminary examination indicates that much of this debris is likely to be from ships and constitutes a failure to comply with MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) rather than land-based sources of marine pollution.

As an EBSA (Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Area), the Sargasso Sea should be considered critical habitat for pelagic species (including fishery resources). With this in mind, we discussed the context of our goals and work plan in relation to the UN General Assembly’s Resolution to pursue a new convention focused on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (for the conservation and sustainable use of the high seas). In part of our discussion, we raised questions regarding the potential for conflict between between commissions, should the Sargasso Sea Commission set a conservation measure using the precautionary principle and based on scientifically informed best practices for action in the Sea. There are a number of institutions responsible for various parts of the high seas, and these institutions are more narrowly focused and may not be taking a holistic view of the high seas in general, or the Sargasso Sea in particular.

When we on the commission reconvened with the scientists, we agreed that a substantial focus for further collaboration included the interaction of ships and sargassum, animal behavior and use of the Sargasso Sea, and the mapping of fishing in relationship to physical and chemical oceanography in the Sea. We also expressed a strong interest in plastics and marine debris, as well as the role of the Sargasso Sea in hydrological water cycles and climate.

I am honored to be serving on this commission with such thoughtful people. And I share Dr. Sylvia’s Earle’s vision that the Sargasso Sea can be protected, should be protected, and will be protected. What we need is a global framework for marine protection areas in the parts of the ocean that are beyond national jurisdictions. This necessitates cooperation on use of these areas, so that we reduce impact and ensure these public trust resources that belong to all mankind are fairly shared. The baby eels and sea turtles depend on it. And so do we.